“Felton X”: Bill Russell

Reading by Josh Ozersky

Although it is seldom discussed today, many famous athletes and entertainers took stands for the Civil Rights Movement. Muhammad Ali refused to be drafted to fight against the Viet Cong and lost his title and millions of dollars he could have earned. Actress Eartha Kitt, an African-American singer best known for playing Catwoman on the Batman 1960s television series, was blacklisted by Hollywood for speaking out against the Vietnam War. As is documented in the excellent film Scandalize My Name: Stories from the Blacklist, many African Americans, including Paul Robeson, Ossie Davis, and Hazel Scott, were targeted during the McCarthy era.

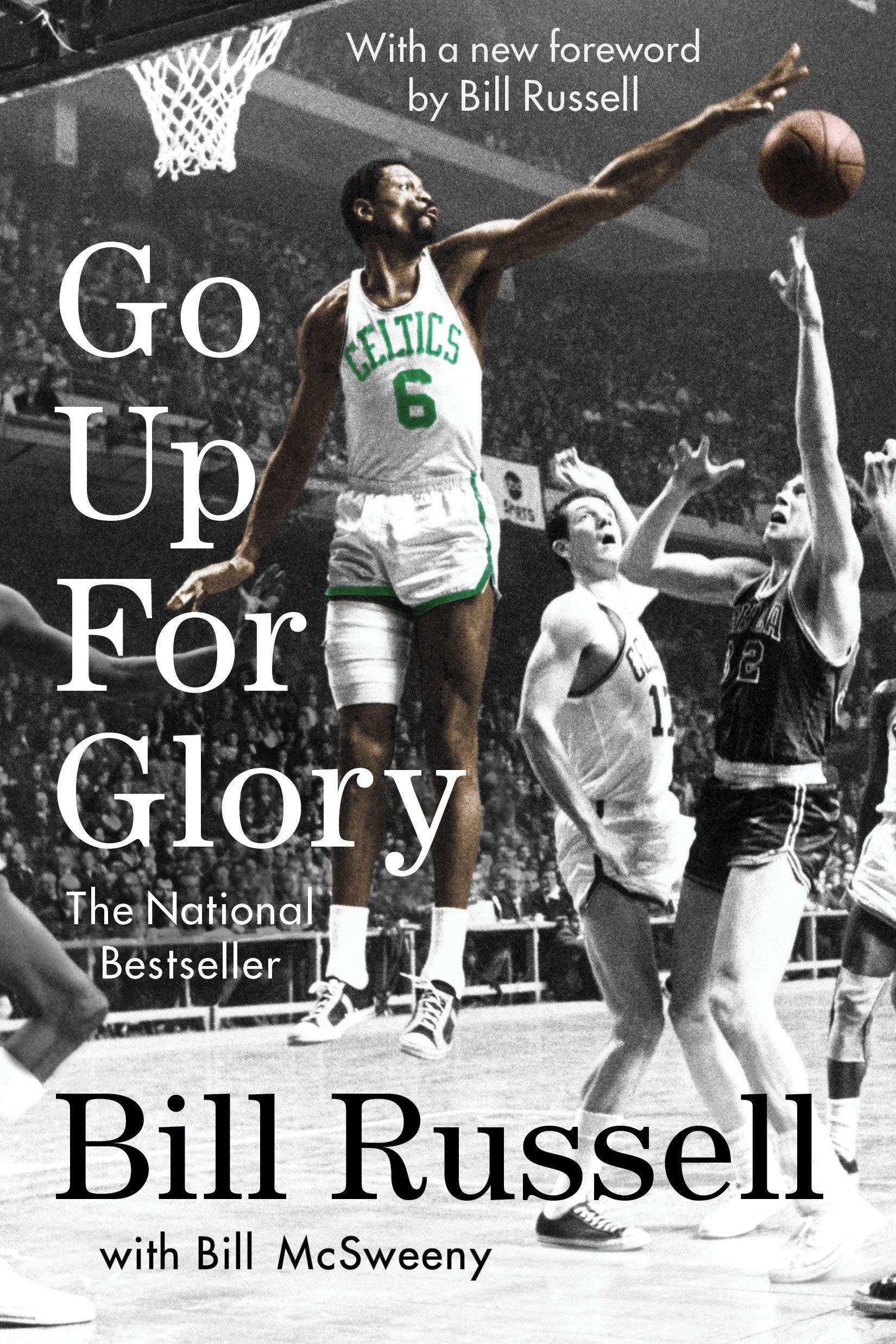

William (Bill) Felton Russell, a basketball star for the Boston Celtics in the 1960s, was nicknamed “Felton X” because he wouldn’t denounce the Nation of Islam. Most athletes and entertainers are afraid to damage their careers by speaking out against injustice, but still a brave few continue today. Actor Danny Glover criticized the U.S. government’s response to September 11, stating, “Bombing Afghanistan and creating the idea that the U.S. is the judge, the jury, and the executioner is the wrong way to respond. It’s hard because of the anger, the pain, and the humiliation we feel about September 11. But we have to understand that other people have faced the same kind of pain, the same kind of anger. Their lives have been transformed by acts of terrorism and violence, often supported or perpetrated by the U.S.” Documentary filmmaker Michael Moore criticized President Bush for the war with Iraq on the 2002 telecast of the Oscars. And Toni Smith, a college basketball player at Manhattanville College in Westchester, New York, has repeatedly turned her back during the playing of the national anthem at the start of every 2003 game as a protest against the war in Iraq.

To learn more about athlete protests, read “Athletes, Protest, and Patriotism,” “Fists of Freedom: An Olympic Story Not Taught in School,” and follow Dave Zirin’s Edge of Sports column and podcast.

Bill Russell (L) at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. National Archives, 542073.

The bare facts of his career say it all: He was the star of a college team that had 56 wins and one loss in two years, winning consecutive NCAA championships. He went off to the Olympics, where he was the star of a gold-medal team that won its games by an average of 30 points. He moved directly from that to the NBA, where he turned a good team into one that was a world champion. He might have qualified for the Hall of Fame had he retired then, but he played for 13 more years and won the championship in 11 of them. He was the first African-American star in professional basketball, the first African-American coach in any major sport, and he is perhaps the single greatest winner in the history of sports.

But his greatness transcended basketball. Unlike other sports stars, Bill Russell was never loved by fans. During his tenure as a Celtic, Bostonians preferred a losing hockey team, the Bruins, to the most dominant basketball squad in history up to that time. In 1958, when he was the NBA’s Most Valuable Player, sportswriters did not name him to the NBA all-star team. Russell himself kept his distance, refusing to sign autographs, making the then unpopular move of calling himself “Black,” and speaking his mind about the Civil Rights Movement when it was still a subject of debate on editorial pages.

William Felton Russell was born in Monroe, Louisiana, in 1934, and when he was nine his family moved to Oakland, California. Instilled with a powerful sense of pride by his father, who was a legend back in Monroe for having faced down the Klan, Russell was impressed by such indomitable historical figures as [Haitian leader] Henri Christophe. His family’s standards of personal integrity were absolute. Even after Russell was making the then immense salary of $100,000 a year, his father continued to work in an Oakland foundry rather than be dependent on his son. This was the mentality Russell brought to basketball even though he knew that to jealously guard his dignity would eventually cause him trouble. “If there was a popularity contest, he wasn’t going to win it,” remembers Arnold “Red” Auerbach, Russell’s former Celtic coach. “If it came to any kind of a vote, he wasn’t going to get it. So he had one philosophy: Everything else will fall into place if you just win.”

Russell set out to win. He had discovered, as a rangy kid on his high school track team, that he could jump higher than anyone else. He had great defensive skills, but was no good at shooting the ball. When he landed at the University of San Francisco in 1952, he and teammate K. C. Jones began to rethink the game.

In the 1950s, unlike today, the coach devised the strategy and the players merely executed it; improvisation and creativity were considered dangerously individualistic. Likewise, it was assumed that basketball was a game played on the floor. Jumping was discouraged, and defensive players were taught never to take both feet off the floor. As for the offense, the jump shot was still considered a novelty, and attempting to play while in the air was disparaged as “playground stuff.”

Players “were primarily Frankenstein look-alikes, more cumbersome than athletic,” the 1950s Celtics star Bob Cousy remembers. They tended to be stocky and muscular, not slender and reedy. When he went to the University of San Francisco, Russell was six feet ten and 220 pounds. How could a player like that compete against men 30 or 40 pounds heavier? Russell’s tremendous skill, combined with his athleticism and what Cousy calls “an almost animalistic motivation,” made the way the game was played seem medieval overnight. Russell was so quick that he could wait until the ball was out of a player’s hands before he left the floor to block the shot. Plays like that lay far outside the coaching manual, and with them he deeply intimidated his opponents.

This cool, remote man was the ultimate team player; he unselfishly blocked shots into the hands of teammates, threw every rebound upcourt to try to give them easy lay-ups. He and K. C. Jones essentially reinvented the game, watching each opponent, cataloguing his tendencies. They came up with new strategies and perfected the art of blocking an opponent by jumping straight up, rather than at him. Along the way they turned basketball into the vertical game it is today. In 1955 and 1956, Russell and Jones led USF to two championships and 56 consecutive wins.

Drafted by the Boston Celtics right out of college in 1956, Russell found himself in a town as racially divided as any he had known. “I had never been in a city more involved with finding new ways to dismiss, ignore, or look down on other people,” he would write later in his autobiography, adding, “Other than that, I liked the city.”

Russell did not let this affect his game. Red Auerbach’s Celtics were a team with finesse that scored high with an up-tempo running style. But the team lacked a strong defense of its own. That was remedied by Russell’s rebounding skills, which were the best in the NBA by far, with 20 rebounds a game. In 1957 the Celtics won the first of what would be 11 championships.

Meanwhile, Russell had become the focus of much attention, which didn’t please him. Autograph seekers found him stubborn and resistant. His reluctance didn’t stem merely from the obvious galling fact that many of the same people who cheered him during a game would have gone to almost any length to keep him from moving into their neighborhoods. He also felt that, race aside, the mixture of servility and rudeness with which fans approached him was degrading to everyone involved. Since his admirers neither knew nor cared anything about him as a man, why should his signature mean so much to them? Eventually, he stopped talking to fans altogether, developing a whole array of defenses. “I used the glower,” he wrote in 1979, “a big batch of smoldering Black Panther, a touch of Lord High Executioner and angry Cyclops mixed together with just a dash of the old Sonny Liston.” As a result, fans stayed away, and their championship team played to many empty seats.

But if Russell’s notoriety brought discomfort with it, it offered a real opportunity, as well. As a celebrity, he could speak his mind about race and society, knowing that, at least as long as he was winning championships, people would listen. In 1959, when the U.S. State Department offered to send him abroad as a “basketball ambassador,” he asked to go to Africa. In Sudan, Liberia, Ethiopia, and the Ivory Coast, he reconfirmed his already powerful sense of Black pride. Because of his refusal to condemn the fledgling Black Muslim movement, sportswriters began to call him “Felton X.”

Russell went right on speaking his mind. At the Great Pyramid at Giza in 1964, it struck him that the calendar was a means of control imposed on the world first by the Egyptians, and then the Romans: “All those Caesars, pharaohs, and popes didn’t hesitate to declare that they were the arbiters of time and that their lands were the center of the earth,” he later wrote, adding with typically mordant understatement, “This is a common way for cultural bias to begin.” Determined that as little as possible would be imposed on him, he defended his rights as tenaciously, and as effectively, as he defended the basket.

It wasn’t easy. In the St. Louis of 1957, where the Celtics played the Hawks for their first championship, Jim Crow was still in full effect, and Russell couldn’t get served in a restaurant; he had to take all his meals in his hotel room. In 1961, he boycotted an exhibition game in Kentucky because two of his Black teammates were refused service in a restaurant. Around this time, he and the other Celtics returned the ceremonial key to the city of Marion, Indiana, to the mayor for the same reason. Russell also made a personal declaration of Black pride and a protest against racism in his 1966 autobiography Go Up for Glory. None of this endeared him to the press, and many white Boston fans again found him too radical. For many blacks he was a hero for using his status as a sports star to advance the cause of civil rights.

Still, basketball was his special genius, and he flourished. Soon he found offensive players who were as gifted as he was. And, of course, the NBA’s most compelling spectacles were his titanic battles with the Philadelphia Warrior (and later 76er) Wilt “The Stilt” Chamberlain, who was to power what Russell was to speed. Chamberlain, who entered the league in 1959, was as fluid and graceful as Russell, but five inches taller and 80 pounds heavier. In the 1961–62 season, he averaged a stunning 50 points a game (a record even Michael Jordan has not broken). Meanwhile, Russell defended the basket with equal passion and ability. To see their confrontations was to come close to witnessing a contest drawn from mythology. In all, the two would meet 142 times and despite Chamberlain, the Celtics almost always won in the playoffs.

By 1966, 10 years’ hard playing in the league had given Russell an unrivaled knowledge of the game and of his teammates. So it was only natural that when Auerbach retired, he asked Russell to coach as well as play, making him the first Black coach in the NBA. There was no master plan when Russell took over. The team played as he did, knowing each other, their opponents, and the game well enough to win without the benefit of a clipboard-bearing general ordering them around. And anyway, Auerbach says, “No one could motivate Bill Russell better than Bill Russell.”

By now, the legendary spring in Russell’s legs was appearing only in spurts, and the aging Celtics found themselves facing a younger generation of quick, vertical, calculating athletes. If Russell had once been a physical anomaly who dominated an NBA filled with earthbound players, this was no longer true. But he was still the coach of the sport’s most famous franchise, and he was still the most feared defender in basketball. In 1967, he finally lost the championship title to Wilt Chamberlain and the Philadelphia 76ers. At the very tail end of his career, he was able to win the title back, and then win it one more time in 1969. By then the public was almost ready to appreciate him.

And by then his politics had caught up with the times. The Black Power movement was in full swing, and even sports players were expressing their politics. But before Cassius Clay became a Muslim in 1964, or Tommie Smith and John Carlos gave the Black Power salute on the grandstand at the 1968 Summer Olympics, Russell had spoken his mind. That, even more than his owning more championship rings than fingers, is what he deserves to be remembered for.

Bill Russell would go on to have mixed success as a coach, executive, and sportscaster before becoming what he is today: the most personable of sages, publishing books, his 1979 memoir Second Wind: The Memoirs of an Opinionated Man and Russell Rules: 11 Lessons on Leadership from the Twentieth Century’s Greatest Winner on advising the Celtics, and, having mellowed with time, even laughing freely in interviews. His old age is now his to enjoy without apology. His legacy remains beyond anyone’s power to limit or tarnish.

© 2003 Josh Ozersky. Reprinted with permission from Josh Ozersky, “Felton X,” American Legacy, vol. 9, no. 2 (Summer 2003).

This essay was included in the 2004 edition of Putting the Movement Back into Civil Rights Teaching. Bill Felton Russell died on July 31, 2022.