Freedom Fighter: The Life and Legacy of Ms. Dorie Ladner

This interview with Dorie Ladner was conducted in 2017 by Maestra Productions in collaboration with Bowie State University Department of Fine and Performing Arts and Teaching for Change. The interview was conducted by Brian Barber and recorded by Kaliesha Perry and Catherine Murphy.

Transcript

Brian Barber: The Freedom Schools documentary, interview with Ms. Dorie Ladner, take one. First of all, I’d like to thank you for taking this interview. It’s an honor and a privilege to conduct this with you.

Dorie Ladner: It’s an honor and privilege for me to be able to participate with you. I’m very encouraged by young people who are doing this kind of work to learn history. Thank you.

Barber: I appreciate it. First of all, let’s get started with you telling us a little bit about yourself, where you’re from, and how it was growing up in Palmers Crossing, Mississippi.

Ladner: My name is Dorie Ann Ladner. I was born June 28, 1942, in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, which is the southern part of the state of Mississippi, near the Gulf Coast and New Orleans, Louisiana. Hattiesburg was a small town with a population, at that time, that was probably forty or fifty thousand. We had and still have two colleges there, the University of Southern Mississippi and William Carey College. Later on, Pearl River Junior College was added. I grew up in Palmers Crossing, which was an all-Black community, and the grocery store in our community was owned by Mr. Hudson, the white man, the only white person I was in contact with at the time.

It was a close knit community. I had a lot of large extended family from my mother’s side, aunts and uncles, grandmothers and grandfathers, and the school and church community. I initially attended the Priest Elementary School, and they later consolidated the school and it became Earl Travillion Learning Center. Later on, I learned that all the Black schools had been consolidated into one center with children from as far away as Brooklyn, Mississippi, which may have been forty or fifty miles, but were bused into Hattiesburg, to Palmers Crossing, to attend school.

We had very limited supplies in terms of material things, books to read; we got second and third hand books from white kids who disposed of them after they’d used the books. We would look up their names in the books, and sometimes three and four names were in those school books that we received from them, and we sometimes called their names out. They had these big shiny buses and a new school which wasn’t too far from us. As I got older, I started learning that they had this nice big school and these nice shiny buses, and here these kids are coming all the way from Brooklyn and other various parts of Forrest County and they were bused in to Palmers Crossing. And I didn’t think it was right.

We didn’t live that far from the school — we could walk — which was less than a mile from where we lived. We could go home for lunch. That stopped when I got into middle school. I had a good upbringing because I enjoyed my extended family. My mother was the fifth of eleven siblings and my grandmother, Martha Gates, who married my grandfather, Joseph Woolen, later on married cousin Bud. We call them cousins, but he wasn’t my grandfather’s cousin because he and my grandpa were not blood related. [My grandmother married him after] my grandfather died. All that went into my own sense of family and community. We had Priest Creek Baptist Church, which was our only outlet because we had the church and school, and then we had the juke joints. That dichotomy was quite stark, because a lot of bootleg liquor was sold in the community. A lot of people sold liquor, and every month the sheriff would come and collect his money from all the bootleggers, and a lot of them were on the street I grew up on. They had juke joints on my street. The influence from them was not negative because my mother and my stepfather did not drink or smoke or do anything. We’d go to the shack and get sodas for our parents. But they gave us utmost respect.

Another thing that made me feel so good was that for every A that I got, I would get a dime from the lady who ran the little juke joint, the chicken shed. Her name was Dot. She said, “Every day, you get an A, I’m going to give you a dime.” And of course, I was too happy to go to her and show her my report cards growing up. That really helped me to understand that somebody else was paying attention to what I was doing. In school, I always had the ability to read and spell. We participated in reading contests and spelling contests, and had a whole lot of extracurricular activities to try, like the 4H Club, National Homemakers of America, the glee clubs, and we traveled across the state participating in all these character building programs that were brought to the Black kids. The white kids had the same thing, but we were segregated.

In the classroom, the teachers sacrificed a lot. When they wouldn’t buy books for us because they weren’t getting money for the library books, the [teachers] would take from their little salaries and put money into the school reading materials and other things that we needed. As I was saying earlier to teachers, our teachers don’t get enough credit for the work that they did for us. They talk about the segregated schools, but our teachers were as well qualified, as well trained, as white teachers. More so in some cases, as some of my teachers continued to graduate work. Miss Mercer went to Indiana University, got a master’s degree, and so forth. But they were segregated. We were privy to a lot of one-on-one training and learning. They wanted us to be the best, and they made sure that we excelled. And I was glad to excel. Of course, my parents were more than happy that we excelled. We had no choice but to excel.

So, all in all, I really liked school, I liked learning, I loved to read. I loved to read. Unfortunately, we didn’t have access to books and newspapers and so forth. There was a medicine man, Dr. McLowd, who sold root medicines — and NAACP memberships, which was unlawful at the time. He would come around and bring books and the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier for us to read, and my mother would talk to him. But that was the only outside reading material that we got. I had this hunger and this thirst for knowledge and wanting to know what was beyond where I was in Palmers Crossing. It was just a curious kind of concern that I had.

Downtown Hattiesburg was segregated, lunch counters were segregated. The only contact that I had with white people was riding the bus. The bus primarily took domestics back and forth to work, from Palmers Crossing to the city, to work as domestics for white people, and so forth. On the bus, the driver was so hateful. I was listening to Mrs. Rosa Parks talk about her encounters with the man who arrested her on the bus when she’d gotten tired [to the point that] she was prepared to be arrested that day. But the only time I came in full contact with white people was on the city bus, because we were told to segregate like South Africa. So, when you came in contact with this kind of nasty and irate behavior, calling you the n word — I used to hear the man say “Get back all you n’s” he would stand up and curse and carry on — and I really resented it. When I was a small child, my mother sent me downtown to pay bills for her, but that was the only contact I really had with white people until much much later.

Barber: That’s super interesting. Wow. That’s amazing. How did you get involved in the freedom movement?

Ladner: Well, Mr. Clyde Kennard, he was a young man who had attended the University of Chicago, was from Hattiesburg, was a Korean War veteran. He returned home because his stepfather died and his mother was running a chicken farm, and he came home to help her run the chicken farm. He wanted to enroll at the University of Southern Mississippi but the powers that be did not want him to enroll because it was a segregated school. At that time it was called Mississippi Southern, but now it’s called the University of Southern Mississippi. So, the first time they said he had come onto campus with moonshine in the trunk of his car. The second time, they alleged that he had been the recipient of stolen chicken feed, and he was jailed and subsequently ended up in Parchman Penitentiary with seven years of hard labor for receiving these five sacks of stolen chicken feed, which he didn’t do. But they did that to keep him from going to school. He was one of my early mentors.

And Mr. Vernon Dahmer was the Forrest County NAACP president and he was very involved in making sure that people attempted to register their vote. At that time, I was not old enough to vote but the elders registered to vote and could not vote. He was encouraging people to vote, ran the Southern NAACP membership, and he owned a lot of land in Forrest County. His home was firebombed by the Klan. His family was able to get out but he engaged them in firepower. He sustained third degree burns all over his body and subsequently succumbed to death maybe a day or so later in Forrest County. He was one of my earliest mentors. He used to drive my sister Joyce and me, along with his sister Eileen Beard, to Jackson, Mississippi, where we met Medgar Evers, who was field secretary of the NAACP. Mr. Evers was killed June 12, 1963.

But, from Mr. Kennard, our NAACP youth council advisor who was put in jail, to Mr. Vernon Dahmer, who was burned to death trying to get out of his house, and then Mr. Medgar Evers was murdered, these were three early influences in my life, people who mentored me. And I have this drive in me, this passion in me, to continue to carry the work forward. Mr. Dahmer’s sister, Eileen Beard, was also an early influence. She was a member of our church, and she and my mother were good friends. So, these are people that I’m honoring every day in my life, trying to uphold the standards that they set, and to carry the work forward. They sacrificed so much for me to be able to be here and to talk to you, and all of us to be able to have a better way of life in this country.

Barber: During that period, with those mentors, how was it, day in and day out, dealings with them? How would you describe a day that you experienced being mentored by Medgar Evers or some of the other mentors that you mentioned? What were some of the things that they did?

Ladner: I’ll say this: in the late 1950s and early 1960s, young people had different roles than they do now. Older people were respected. Like, I’m called Miss Dorie. And that’s why we respected them, and we would sit and listen. We wouldn’t engage them in a lot of dialogue because we would listen and learn by example. Mr. Evers did talk to us about our rights, about my parents paying taxes and not getting the full benefit of paying taxes. We didn’t have sidewalks, we didn’t have street lights, we didn’t have a lot of things in the school I attended. The toilets and the sewage line were not good and sewage was running on the campus. But we didn’t have a day-to-day kind of engagement with them. They were so much older than we were and we were children in their opinion.

Now, as I got older, I enrolled in Jackson State University my freshman year because the University of Mississippi and William Carey University were segregated, so I had to go 90 miles north to Jackson State. Mr. Medgar Evers’ office was across the street from Jackson State. Every Wednesday we got a half day off, so I would go across the street and talk to him about my freedom. At that time, he would talk to us and tell us about freedom. You know, we unsophisticated didn’t really know that there was no movement activity. But I had this feeling that I didn’t want to live this way.

See, I had been exposed to Emmett Till’s death. That was the beginning of my awakening. He was a year older than I and I felt that if they had done it to him, they could do it to me. Although he was like some 200 miles north of where I lived, I felt his pain, looking at his photographs in Jet magazine, and reading about his case and looking at the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution being cited. But I didn’t know what they meant, because I had never heard of the Constitution. So I went to my social service teacher, Mr. Clark, and I said, “What does this mean, 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments?” He said, “That has something to do with the Constitution.” I went and found the Constitution and I memorized those articles for my own empowerment. I was like 14 years old, but I felt it would make me feel better, which it did. But I still had this yearning and this passion, this desire, to want to know more.

My real contact came at Jackson State, when Mr. Evers’ told us that some people were coming to help us get our freedom. I didn’t really know what that meant, but he was talking about the Freedom Riders. We’d already been tear gassed on Jackson State’s campus and been subjected to being expelled because we marched in solidarity with nine students from Tougaloo College, where I later graduated from, a private school, because they attempted to desegregate the public library in Jackson, Mississippi. Blacks could not attend that library. And we attempted to embark in solidarity with them, but we were teargassed coming out of Jackson State’s campus. There’s a whole long story about that.

But that only made me want to do more. And being expelled from Jackson State, there’s a long story about a prayer in a dorm. My mother was strict, always talking about children having their place, teaching your children to be quiet when adults talk, teaching your children not to engage in adult conversation. But the dorm counselor went and told the dean of students that I had prayed a prayer, and he needed to talk to me. I was president of the dorm counsel, so she told me that the dean wanted to see me. I told my sister Joyce and she said, “You want me to go with you?” I said, “Yes.” So we went there and they wanted to know about the prayer that I had prayed. I was critical about this, because we grew up in the church. It became nonsensical to me, questioning me about a prayer. The only thing I knew about Montgomery, Alabama, was I heard some people were walking in Alabama. That was how much news we were getting, because the media would not give us information. They say information is power, well we were not getting information. There was a dark curtain pulled down. We had no access to outside information. That’s how much in the dark we were.

So when he started asking about this prayer, that was dean Gill, so dean Gill referred me to the dean of students, Dr. Oscar Rogers, who graduated from Tougaloo College and Harvard University and he came down very hard. He said that he didn’t want anybody on campus disrupting things and so he said, “Ms. Ladner, I’m going to hip you before I ship you.” And I’m still very much in the dark, but to make a long story short, I was expelled and my sister was expelled by default. So I said, “I don’t want to be on this campus anyway.” And I was forced to begin to take more action.

James Meredith was on the campus, before he attempted to enroll at the University of Ole Miss, and a lot of other young people who were in the Greek Panhellenic Council. I pledged Delta Sigma Theta sorority at that time. We were sitting in the student union building talking and they were able to school me even more. I was 17 years old and they were upperclassmen, and Mr. Evers was engaged with us, but when we went to Chicago that summer and worked and came back, and enrolled at Tougaloo that fall, I didn’t see Jackson State anymore.

At that time, when I got back, the Freedom Riders were there and I was like, “Oh my God, hallelujah, hallelujah.” And 1072 Lynch Street, you’ll hear me use that because that’s where all the meetings were held and where Mr. Medgar Evers’ office was, right down Lynch Street, 1072, it was a Masonic temple. So I got there and met all the young Freedom Riders there, young Black and white people from across the country who had ridden in on the buses. I saw Marion Barry, Tom Hayden, Casey Hayden, John Lewis, Charles McDew, all these young people, and thought, “Oh my god, where have you been all my life?” Because I was isolated. I was like a child in the wilderness, sort of dangling around looking for somebody to look up to, and when they came there in full force — Diane Nash, Julian Bond, all these folks — I thought, “Oh my god, where have you been all my life.” That was the beginning of my real awakening in terms of making these connections with young people such as myself. Some of the Freedom Riders remained and Mississippi, and they opened an office on Lynch Street. And Lynch Street is significant because John R. Lynch, initials J. R. Lynch, was a Black representative to the United States Congress during Reconstruction, a young Black man. So the street is named for him.

But we were so fully engaged at Tougaloo College, where there were no restrictions and it was a very relaxed atmosphere while learning. Also, we had all kinds of arts and all kinds of people coming to campus. Dr. Martin Luther King came to campus, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, all kinds of people came to campus. Dr. Ralph Bunche. This was so much of an enrichment for us to be able to meet these people. Jackson State was a state run school, that’s the difference. Tougaloo College was one of those colleges set up during Reconstruction, the same as Howard University and others. So it had its own charter, and the state kept trying to revoke it but they couldn’t. I felt so relaxed. Then I met a cadre of young people on Tougaloo’s campus that were from Mississippi.

In the summer of 1962 was when I went to the [Mississippi] Delta and started working with Bob Moses and Charlie Cobb. I met Charlie there. He was on his way to Texas, to an NAACP meeting, and he stopped at our office on Lynch street. Lawrence Guyot, Jesse Harris, and I were in the office and he said he was going to an NAACP meeting in Texas. They said, “Why are you going there? The revolution is here.” So they got in his face and he decided he’d stay in Mississippi. That’s how Charlie started working in Mississippi. We went to the Delta and I remembered about Emmett Till being murdered in the Delta. Then when we went to the Delta, to organize a Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), that was a whole other thing, because I didn’t know that Black people were not allowed on the streets after sundown. You could not be seen on the streets in a lot of these towns, and I was a victim of it along with the people in the car I was riding with, including the driver. He was arrested when the Council of Federated Organizations, known as COFO, was founded in Clarksdale.

Barber: And you’re one of the founding members?

Ladner: Yes. We rode up there and the police stopped us on the side of the road and said we’d violated the curfew. I’d never heard of it, and I’m from Mississippi. But these are all the kinds of things that my ancestors were confronting. And I said, “No, no, no,” and we decided to stay in the Delta because that’s where you had the largest majority Black population. Amzie Moore, the local NAACP president, had asked Bob Moses, who ran a project there to register voters. That’s where we found Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer in that county, and the rest is history. Mrs. Hamer was taken to the courthouse along with a busload of other people from the plantations and they were not allowed to register to vote, but the movement started there in the Delta.

Barber: Can you speak to your experience as a woman in those days, during that movement with so many men?

Ladner: Well, I saw myself as a freedom fighter and never thought about my gender, so to speak, because I had my own vision about what I saw for Black people, and what we should have, and what we didn’t have. I use a phrase, the line was drawn in the sand, and I stepped over the line. I didn’t see it as being a female or male role, all I knew was that I had to do something about what was going on with my life and my people. And that is how I saw it. Now, these other individuals happened to be male, that was coincidental. I was a part of whatever was going to happen, and I was in the forefront, and I wanted to remain in the forefront. I was never what you would call scared, but I’m not saying I was foolish or anything. I have this personality that doesn’t frighten easily. Some people said I’m intimidating, but I don’t see it that way. I see it that if my rights are involved, I will fight to the death.

Barber: That probably speaks to your position as one of the founding members of the Council of Federated Organizations.

Ladner: Yes. We had begun to work with Bob Moses, Robert Moses, who helped to develop the project in Mississippi. It was Charlie, the late Jesse Harris, Hollis Watkins, myself, MacArthur Cotton, a lot of us joined him to start working in Mississippi, primarily on voter registration because they’d had a discussion about whether this should be sit-ins, and everybody knows that Mississippi wasn’t big enough to curse the cat. There was nothing there to integrate, so to speak, in terms of Woolworth’s lunch counters and all that. The direct action was actually going to the courthouse to attempt to register to vote. We’d already experienced one death, Mr. Herbert Lee, who was killed in Liberty, Mississippi by a state representative, E. H. Hurst, while trying to register to vote. He was shot in cold blood right there in the town square, and the state representative, Hurst, never served a day. And the deceased was accused of starting the fight. That story was passed on down to me when I joined SNCC. Mr. Herbert Lee was killed in cold blood.

The education came, the literacy came, in a lot of forms, because in order to register to vote, you had to interpret these amendments to the constitution of Mississippi. The shortest one, if I recall correctly, was “no person shall be imprisoned for debt.” That was the shortest one, and you would try to interpret it to the best of your ability to the county clerk there. And you never passed. A lot of people were not able to read or write, and that was due to early on, they had not been given the monies passed down from the Freedmen’s Bureau to the different counties for Black people to be able to go to school. The money was taken by the local authorities and used to shore up their plantations, and used to get what they wanted. Bob Moses is trying to get an education amendment to the constitution passed in the United States of America right now, because how can you hold people responsible for being illiterate when you have denied them education?

Going back to the whole issue of literacy, as I started out, education was emphasized in my home by my parents and my relatives. They didn’t have a very formal education, but they felt that we should know how to read and write and should be educated. My mother always said, “Go to school, get an education, work, and take care of yourself. Don’t depend on any man to take care of you.” I started hearing this early on. “Be independent,” she was saying, “work and take care of yourself.” That was with me. So, I figured that if I got an education that I could take care of myself. And I was always fiercely independent. So, when I left home that June 1962, after school was out at Tougaloo College, I went back to Jackson, and I told my mother when I got home, as I packed my little orange suitcase and Palmers Crossing, and on my way out the door I said, “Mother, I’m going to Jackson to work with Bob Moses to get my freedom.” And mother turned around and she didn’t know what I was talking about. I dashed out the door, the screen door slammed, and I ran down to the Greyhound bus station, got on a bus, went to Jackson, and went to their Freedom House on Rose Street.

Now, at the Freedom House, there were all these guys there. So I went and found my own bed. Sometimes we had to sleep together, [but] that didn’t matter, because we were there for freedom. We weren’t there for intimate purposes. We were very vigilant about our work. When your mind is on issues, you tend to delay a lot of things in terms of intimacy and so forth. I knew that being only female, I wouldn’t be effective if I started sleeping around with the guys anyway. I couldn’t be effective. So, I got into the Freedom House, and shortly after being there is when we went to Clarksdale for the founding of COFO, and we all rode up there.

As I said, I had read about the Delta, and heard all these horrible stories. Emmett Till was murdered there. I’d never been there, but when I got there, I had this horrible feeling. In time we got into this meeting and the fire department came and said they heard there was a fire there. They came in with a waterhose and they said, “There’s no fire here.” They were trying to intimidate us. We didn’t move, so they waited until midnight, we were journeying and they said we had violated the curfew. Dave Dennis from CORE was the one driving the car I was in, along with Colia Liddell, my cousin Mattie Bivins, and Lester McKinnie, who’s also known as Baba Zulu in Washington, he was a Freedom Rider from Tennessee.

The police stopped us on a dark highway just before we got to Mound Bayou, an old Black town. Mound Bayou is a very significant town in the annals of black history. But we didn't make it to Mound Bayou and the police stopped and kept Dave Dennis in the back of their car behind us for almost an hour. Dave came back and said, “This man is crazy. He said he wants to take me to jail. He asked me about my dad, asked me where I got these blue eyes from, and said he’s going to arrest me. Y’all follow me back to jail.” So we proceeded to follow him to the jail, and we went inside and they told us to get the hell out of there. We didn’t know where we would go. I mean, the Delta is blacker than a thousand midnights. Nothing but the stars and these flatlands, and we were bumbling around this car just frightened to death. I mean, really scared. But we got to Amzie Moore’s house in Cleveland, Mississippi, between five and six the next morning.

We had to go through this little town called Ruleville, and we had been told that the man who was the nightwatchman in Ruleville was one of the brothers who murdered Emmett Till, the older man Roy Bryant. And oh my god, when I saw the sign that said Ruleville, I was on the floor of the car and I said, “Lester [McKinnie] the speed limit is 22 miles per hour, so don’t go over or under 22.” I was frightened to death. So, when we got to Amzie Moore’s house, all that fear had been washed away. This is what Booker T. Washington said, “Put your bucket down where you are.” And that’s where we remained and started working for real.

But getting back to education, the whole thrust of the Freedom Summer was because in order to do anything, you had to have some form of literacy. There were people who were driving without driver’s licenses, but they’ve been able to function in the little communities where they were because they knew the powers that be — the sheriff or the deputy — and most of the people were illiterate, [both] white and black. Let’s face it. So they were able to get by. The parents had been able to go to the store; you live in these little, small communities, and they did not read. But when their children were going to school — I was born in 1942, my mother was born in 1921, and her mother was born in 1896, so you’re talking about two or three generations removed from enslavement — so the education was being handed down, making sure your children and your grandchildren were being educated. And a great deal of emphasis was placed on that literacy because so much had been taken, and all kinds of other things were taken away from you because of your inability to be able to read and write.

I’ve looked at some records — I do a lot of genealogical research — where one of my great, great grandfather’s had picked all this cotton, and he came from Chickasaw County, Mississippi [but] was born in South Carolina. He picked enough cotton to buy hundreds of acres of land in Wayne County. But then I saw how he’d begun to lose it by signing a document, one of the sheriffs or clerks or somebody had him sign and he started losing the land. So they understood they were losing, but they couldn’t understand what was on the dotted line. My grandparents could read and write. My dad was born in 1914, his birthday is June 13, 1914, and his mother was born in 1888. So, they wanted to make sure that all their children were literate.

In the movement, with everybody coming together from all parts of the state, I dare say that this was the first time that people from across the state of Mississippi, and mostly southern states in the United States, had been able to join forces. During the Reconstruction period, we had only like seven to eight years of so-called freedom before the Black Codes were enacted and the Klan came back in and started reinforcing segregation at the height of the Confederacy, intimidation, taking land and people. There were some schools; I can’t say everybody was not educated. But the mass majority were not educated. And people knew that if you knew how to sign on the dotted line, knew how to read, and knew how to write, that they can’t take that away from you. They always said, “You get you educated and they can't take it away from you.” I heard that all my life, too. Get an education and they can’t take it away from me. And that’s what we’d learned. And most of the people that I knew in my community wanted us to learn how to read and write and to be able to count. Most people counted in their heads anyway. The fastest counters that I’ve ever encountered were people who are illiterate, but they could count money and they could count it backwards and forwards and everything. They couldn’t read and write, but they could count.

With the COFO infusion of people like James Forman, executive director of SNCC, who was a school teacher himself, an organizer with CORE. He came in with the whole concept of literacy, as well as Bob Moses, who had been a school teacher in New York and attended Harvard and was teaching school when he came to Mississippi. So, a lot of the kids from the north came. Charlie Cobb attended Howard University, and a lot of kids, and Howard came from Mississippi. I was at Tougaloo College, and a lot of us from the college community went into the movement. But then you had all the others in the community who were part of the movement. Each person contributed in their own way whatever they could.

Everyone was not a starMichael. We used to tell Stokely [Carmichael], “Sit down starMichael,” if he kept talking. But it meant that everybody had a turn. You may not have been as articulate as he was, but what you had to say was important. Everybody had a role. The whole concept was drawn out by Miss Ella Baker. Miss Baker was of the opinion that everybody should participate. It was a democracy, and all the students who were in the room, who came together in SNCC, had the right to have something to say about what they were going to do in terms of the organization. Whatever the plan was, we’d strategize, we didn’t just get up and go outside and say we’re going to demonstrate. We strategized for maybe two or three days, 72 hours, to determine. It was done by consensus. So, everybody had their input. And once you went over all this, then you would decide what you were going to do. By doing this, each person was learning, it was a learning process, and a community of people were the same way. Your biggest meeting places were your churches. We didn’t know where to go, but to the churches as they were the largest places. A lot of ministers participated, and some of them didn’t. We had ministers from the churches and we had two children. One of the most effective places was Birmingham, Alabama, where the kids came out when the parents came out. This way you organized the movement.

I know I’m going on and on and on, but the whole concept of literacy has been something that, when I think about the people in my family, like my father’s father and mother, who could read and write, and my mother’s parents could read and write, because when you look at the census forms, if you’re doing any type of genealogy, they have whether or not the parents can read or write. And my great grandmother could read and write. During the Freedmen’s Bureau time, they had people come in, instead of schools, and they started teaching and talking, like Howard University and the older colleges. A lot of kids weren’t able to go because the same thing that happened after the seven to ten years of Reconstruction, people went back to that whole sharecropping system. Right back there at the man’s place who mistreated and enslaved you, then you went back as a sharecropper, [which is] another form of enslavement.

Michelle Alexander called it The New Jim Crow, but my insistence is that it never went away. It’s not new, it’s the same thing that has been there all the time. It’s maybe more urban, but my exposure to it never left. There’s some added things to it, like mass incarceration, more jails being built by private entities to incarcerate more people, which is another form of enslavement, but it’s been there all the time. I know at Parchman Penitentiary in Mississippi, one of the largest prisons in the country, they enslaved people on what was nothing but a big plantation. When we worked in the Delta, several of our people, including Charlie, spent time at Parchman Penitentiary.

Mr. Clyde Kennard was sent to Parchman. Before he died, he told me that they made him go out there and pick cotton. He was so weak, he was dying from stomach cancer, and he was wearing broken shoes, and the mud was so thick on the ground that it pulled the soles off his shoes and he would fall into the mud on the ground. And these guards had the inmates pick him up and stand up and make him try to pick cotton again but he was too weak to stand up. That was the form of enslavement that they were subjecting him to because he dared try to enroll in an all-white university. They were teaching him a lesson, and that lesson was supposed to be sent back down to all of us.

I remember maybe eight or nine guys getting arrested in Greenwood with SNCC. I saw them in the courthouse in Greenville, Mississippi, their heads all shaved, and they had lost so much weight, they were emaciated. When I saw them come in, they had lost like 30 pounds or more. And they were attempting to get people registered to vote. So all this, I would like to say in a few words, has been some of my experiences, that there’s nothing new, but I see more sophistication in a way with these so-called, started with the Richard Nixon, war on crime and the war on drugs, and whatever term they want use to highlight an epidemic that they’ve already started. All these weapons of mass destruction, both abroad and in this country, are purposely put into our communities to eradicate us and keep us enslaved. The guns don’t come by accident. The same gunmakers who send them to Iraq and Iran are the same ones who put them in Baltimore and Chicago. Same manufacturers, same people. They’re making money, they don’t give a damn who buys them. All they want is the money. They don’t care who they kill, because it’s about money first, and control.

So, each morning when I get up, I see a new day. I’m talking about darkness, but each day brings about new sunshine to me. In my darkest hours, when I used to go to bed at night not knowing whether or not I would get up the next day, in Natchez, Mississippi where the Klan was riding around, and the chief of police said, “I thought we’d killed you” as they attempted to blow our house up. But I said, “No, I’m still here.” The point is that each day is a new day. Darkness may be here today, but the next morning when you wake up, it’s a new day. Some people don’t wake up, but the point is that as long as we are awake, we must work, we must do something to contribute to mankind, to make the world a better place. Everybody.

You can’t just say, “On my street, we’re going have a stop sign and we’re going to have street lights,” because the next street over is dark. So you want light to be everywhere, right? Enlightenment, enlightenment. And that’s the way that I came into the movement, I came to the movement as a Black person from the state of Mississippi, and I was 14 when I started. You can hear me on Sirius XM radio, go to Dorie Ladner photo contact, and Sirius has a little excerpt there from an interview that I gave when I was going to Natchez, Mississippi, a 2014 interview with them at Sirius XM. But my whole contention was that they were having Dorie Ladner Days and he said, “Aren’t you excited?” I said, “No. It was never done for the glory. It was done for the people.” Why me, but I’m just a cog in the wheel. One spoke in this wheel. It takes all these spokes to make this wheel go around. And we don’t ever want to say that I’m the only one, no. Before me there were many and after me that there will be many, hopefully, and all around us, there are people. What we want to do is empower everybody. That’s the only way that we can make it whole.

Barber: Thank you so much. That’s beautiful. Thank you.

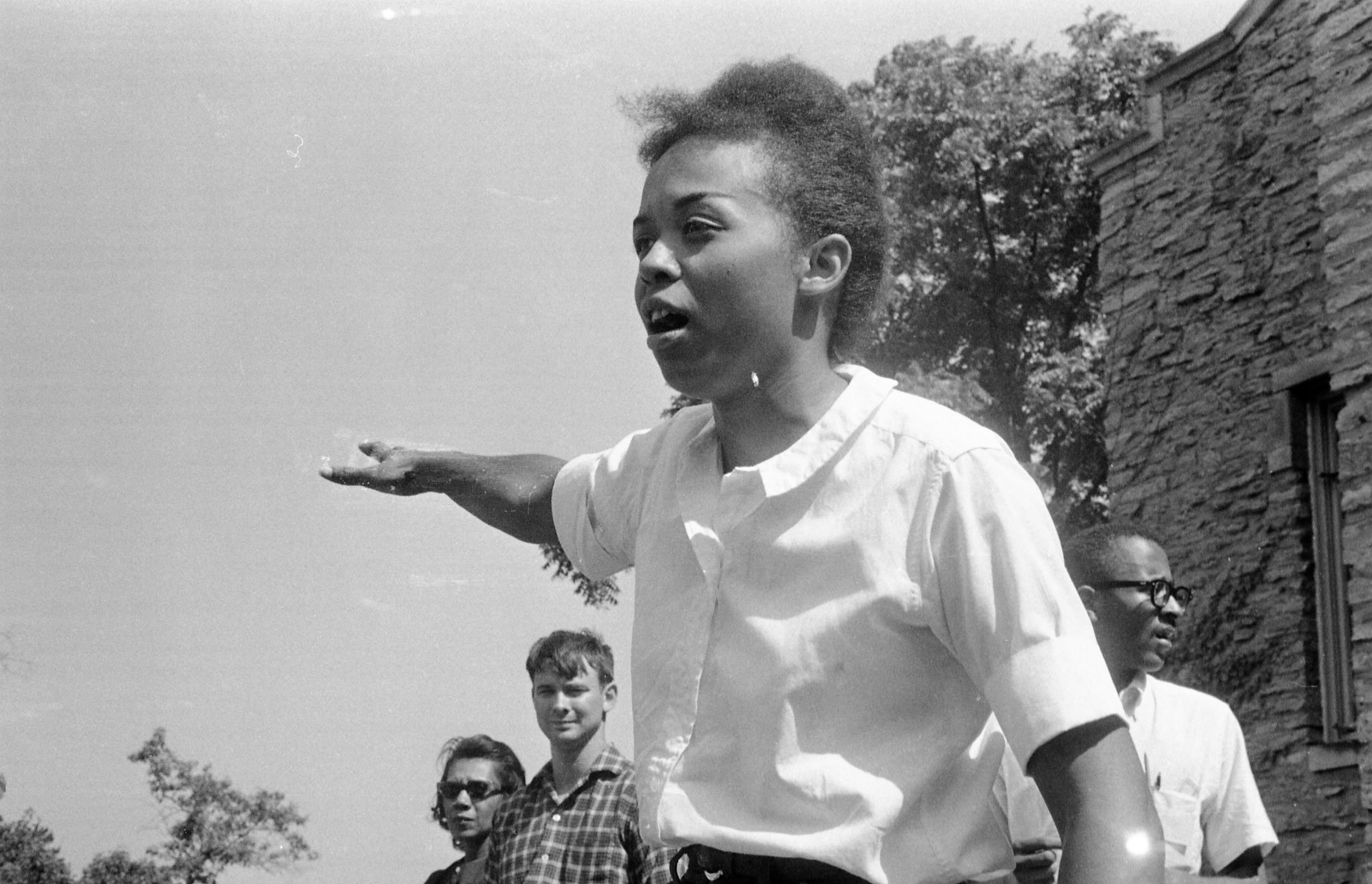

Dorie Ladner at Freedom Orientation in Ohio, June 1964. Herbert Randall Freedom Summer Photographs, USM.