Exploring the History of Freedom Schools

Lesson by Deborah Menkart and Jenice L. View

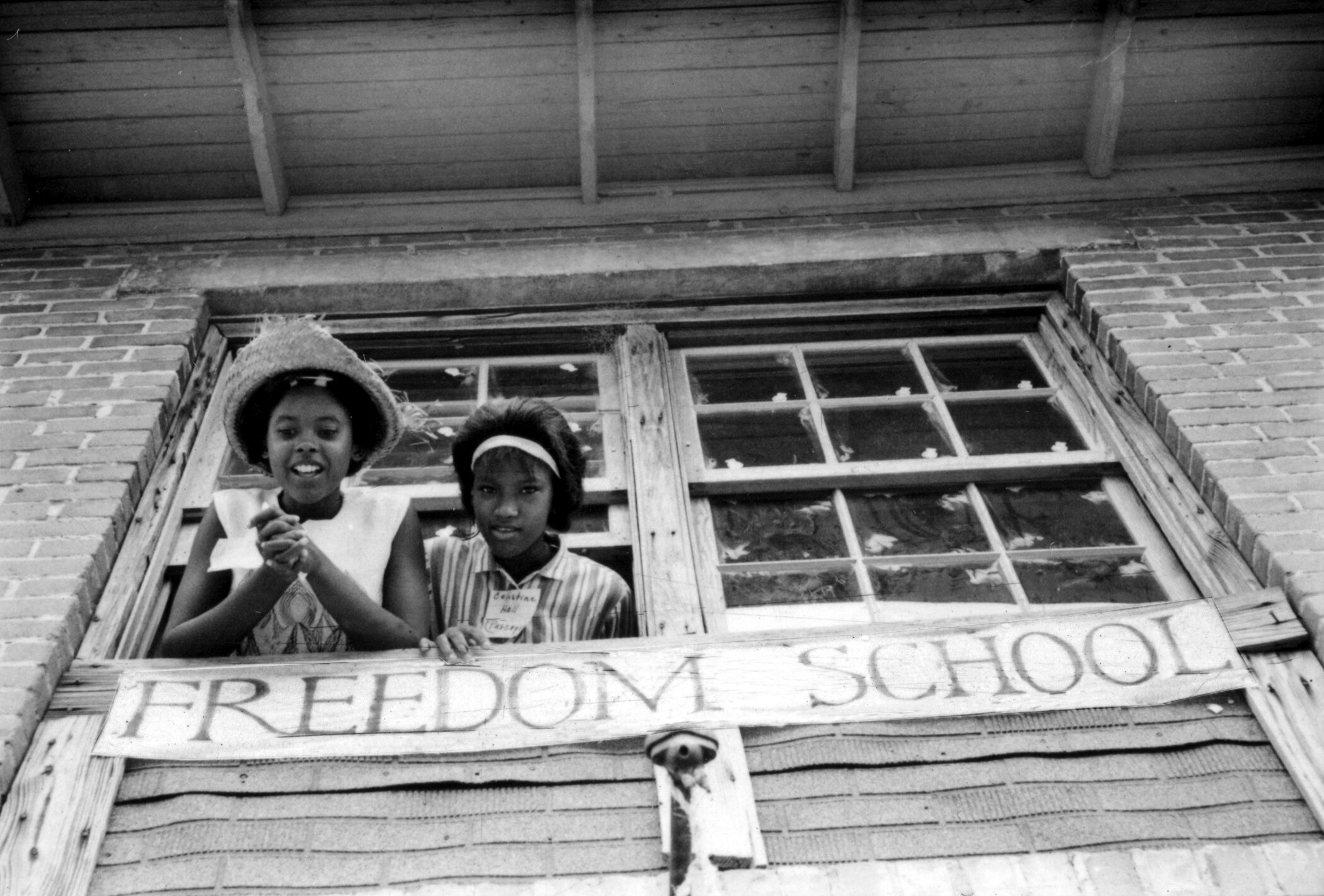

Two girls look out the window of a “Freedom School.” © Ken Thompson, United Methodist Board of Global Ministries

Education should enable children to possess their own lives instead of living at the mercy of others. — Charles Cobb Jr.

The Freedom Schools of the 1960s were part of a long line of efforts to liberate people from oppression using the tool of popular education, including secret schools in the 18th and 19th centuries for enslaved Africans; labor schools during the early 20th century; and the Citizenship Schools formed by Septima Clark and others in the 1950s.

The Freedom Schools of the 1960s were first developed by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the 1964 Freedom Summer in Mississippi. They were intended to counter what Charles Cobb refers to as the “sharecropper education” received by so many African Americans and poor whites. Through reading, writing, arithmetic, history, and civics, participants received a progressive curriculum during a six-week summer program that was designed to prepare disenfranchised African Americans to become active political actors on their own behalf (as voters, elected officials, organizers, etc.). Nearly 40 Freedom Schools were established serving close to 2,500 students, including parents and grandparents.

An exploration of Freedom Schools allows students and teachers today to explore the purpose and possibilities of public education today.

The study of Freedom Schools should take place in the context of the long struggle for freedom, voting rights, and quality education in the United States as a whole.

This lesson uses primary documents in a jigsaw format to introduce the history and philosophy of Freedom Schools. The readings allow students to take on the role of historians, combing through primary documents from the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools documents provided by Education & Democracy, Civil Rights Movement Veterans, the SNCC Digital Gateway, and the University of Southern Mississippi Digital Collections. These include student newspaper clippings, a brochure, curriculum excerpts, a map of Freedom School locations, teacher orientation materials, and more.

Students will discover that the Freedom School curriculum was designed to spark consideration of daily oppression and shaped to serve a liberation struggle. For example, the stated purposes of the lesson “Material Things and Soul Things” were:

To develop insights about the inadequacies of pure materialism; and

To develop some elementary concepts of a new society.

The writing by Freedom School students shows the sophistication of their political analysis at a young age. For example, in the newspaper Palmer’s Crossing Freedom News, 11-year-old R. M. C. writes [sic],

I like to go to Freedom School. You would like it too. If you want to come and don’t have a way, let us know. I think we should all have our equal rights. We Negroes have been beaten, but we will never turn back until we get what belongs to us. We just want what belongs to us. We don’t want anything else. I think we as Negroes ought to have the right to vote for justice, equal rights, freedom, jobs, we need better books to read. In the stores uptown and down here we have to pay tax. That is a crying shame. God is looking down on people now. We try to hid things form people, but we can’t hide things from God. We pay tax. I think we should have a right to vote. All of our colored men are getting beaten and put in jail. This unfair I think, don’t you?

The lesson is inquiry-based, hands-on, and engages students in critical reflection. Therefore, students learn about Freedom Schools not only from the readings, but also from experiencing the pedagogy.

Grade Level: High School

Time Required: One or more class periods

Materials

Expert Group Discussion Questions. Make enough copies for each student in the Expert Group.

Expert Group Primary Document Packets. Make one single-sided copy of each packet.

Background Reading

For background reading by the teacher before introducing the lesson, we recommend the article “Freedom’s Struggle and Freedom Schools” by Charles Cobb Jr., The Freedom Schools: Student Activists in the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement by Jon Hale, and the website Education and Democracy, which offers an extensive archive of the Freedom School curriculum.