Each School Had a Graveyard: Native American Boarding Schools

Lesson by Deborah Menkart

View of the Carlisle Indian School cemetery in the 1930s after the graves had been moved from their original location. © Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Native American boarding schools were part of a U.S. federal government strategy to dominate and assimilate Indigenous Peoples. One popular slogan of the assimilationists was “kill the Indian, save the man.”

Begun in the late 1800s and continued through the mid-20th century, this education policy was directly tied to U.S. government efforts to take over even more of the tribal land in the face of strong resistance from Indigenous Peoples.

As a report on the Canadian Residential Schools explained, “The goal of obliterating these peoples was connected with stealing what they owned — the land, the sky, the waters, and their lives, and all that these encompassed.”

The boarding schools were designed to teach (force) Native American children to give up their heritage and become anglicized. Children were torn from their families and everything they knew.

There is dramatic evidence of the impact this had on the students — so many Native American children died of illnesses, mistreatment, and sadness in the boarding schools that each school had its own graveyard. This despite the fact that many children were sent home when they were near death in order to lower the death counts at the schools.

Objectives

Students will engage in historical investigation in order to uncover a significant yet seldom taught aspect of the history of Native Americans.

Students will examine primary text and visual sources to gain an understanding of the ways in which theories of race and assimilation affected education policies in the past.

Students will compare the education policies and practices of the Native American boarding schools with those of the civil rights era and today. Students will then be able to explore issues of continuity and change in American history.

Students will demonstrate an understanding of Native American 19th-century experiences and strategies through point-of-view writing.

Materials

Photographs

Student Readings

Resistance Readings

Background Readings

Preparation

This lesson is best introduced to students who have some context, including having been introduced to the lives of Native Americans in the late 1800s and early 1900s and the devastating impact of the land takeovers by whites as they pushed west across the continent.

Copy the photos so that children can view and discuss them in pairs.

Before the class, ask seven students to be readers. Give each of them a reading and ask them to practice reading it aloud so that when it is their turn to share it with the class, they can read it dramatically.

Copy the readings to share with all the students following the dramatic reading.

Procedure

Tell students that they will be learning about a critically important yet seldom taught part of the history of this country — the Native American boarding schools. Beginning in 1879, these institutions were part of the United States government’s plan to “assimilate” the Indigenous People of this country. Discuss the meaning of “assimilate” with students.

Ask students, working in pairs, to look at the photos. Have them discuss and list on a sheet of paper five things they notice and five things that they wonder about. After most students have at least three items on their lists, ask them to share some of their observations and questions for you to list on a shared screen. Try to take one comment from each pair.

Tell students that to help them answer some of their questions, they will listen to testimonies about and reports on the boarding schools. Then have the selected students read their respective texts.

Following the readings, ask students what new insights or answers to their questions the readings provided and what additional questions they have.

On a map of the United States, point out South Dakota and ask a student to point out Pennsylvania. Tell students that Luther Standing Bear was taken from his home in what is now South Dakota to the Carlisle School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Ask them to locate Carlisle. Have a student measure the distance on the map, and then have students in groups compute the distance in miles. Ask students about the effects of the school’s distance from the reservation.

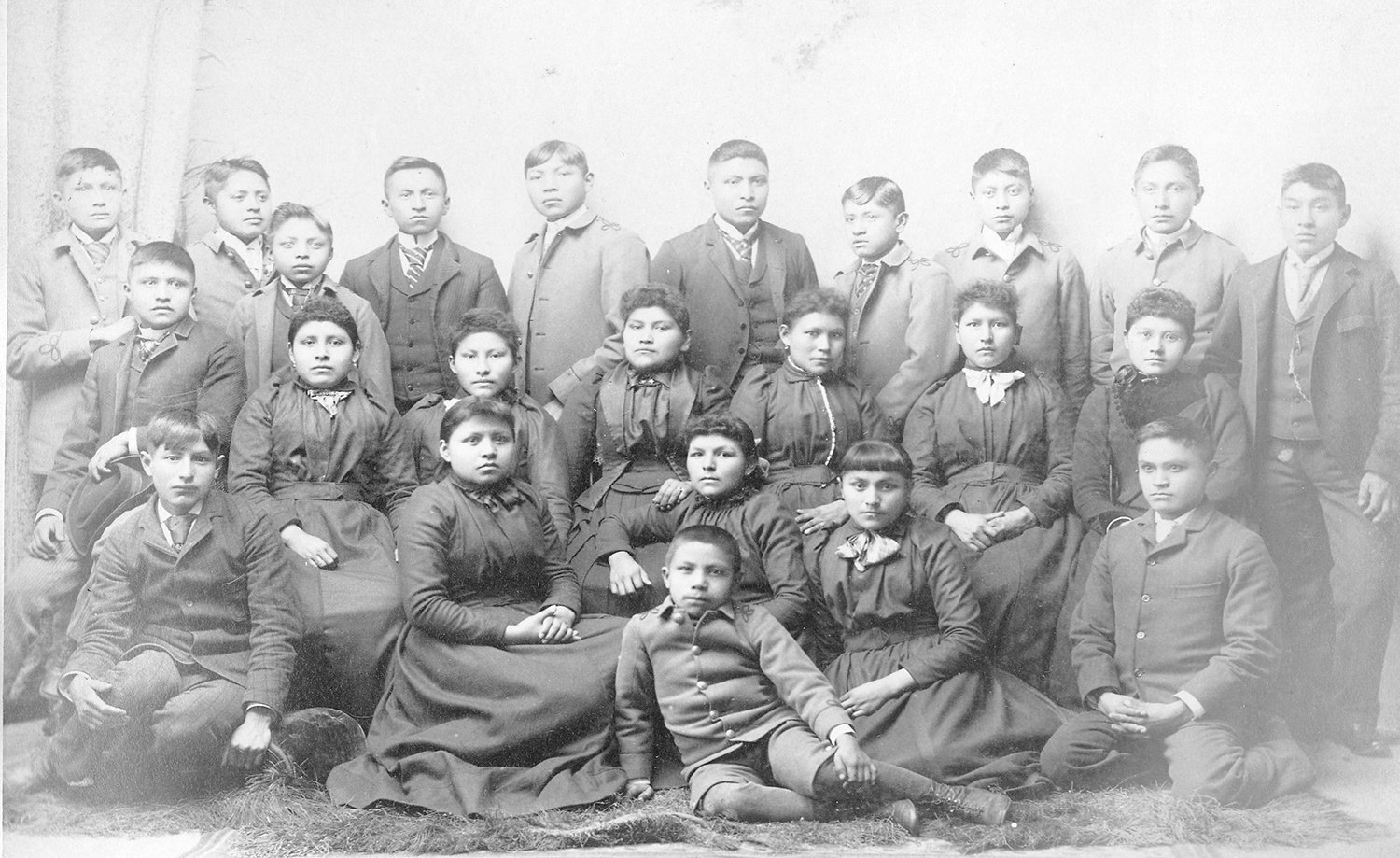

Show students the photo of Zie-wie Davis upon her arrival at the Hampton Institute and ask them to write an interior monologue from her perspective: “What is she thinking?” Ask for volunteers to share what they have written.

If time allows, share the background reading. Ask students to discuss why they think the schools were established. Who benefited? Who lost?

As part of this lesson, it is important to share stories of resistance. If the age group is appropriate, show the film Rabbit-Proof Fence. Otherwise, have students do a dramatic read-aloud of the two resistance readings included in the handouts.

Either through a discussion or a written assignment, ask the students to consider the following questions:

Given what we have learned from our research and the readings, what was the purpose of schooling for Native Americans in the period 1875–1925?

How do the conditions and the purposes of your school today compare to the boarding schools’ conditions and purposes?

Some of the well-meaning teachers were trying to “help” the Native American children, yet their actions had negative consequences. Today, are we as individuals or as a society doing things to “help” people while actually hurting them?

Materials

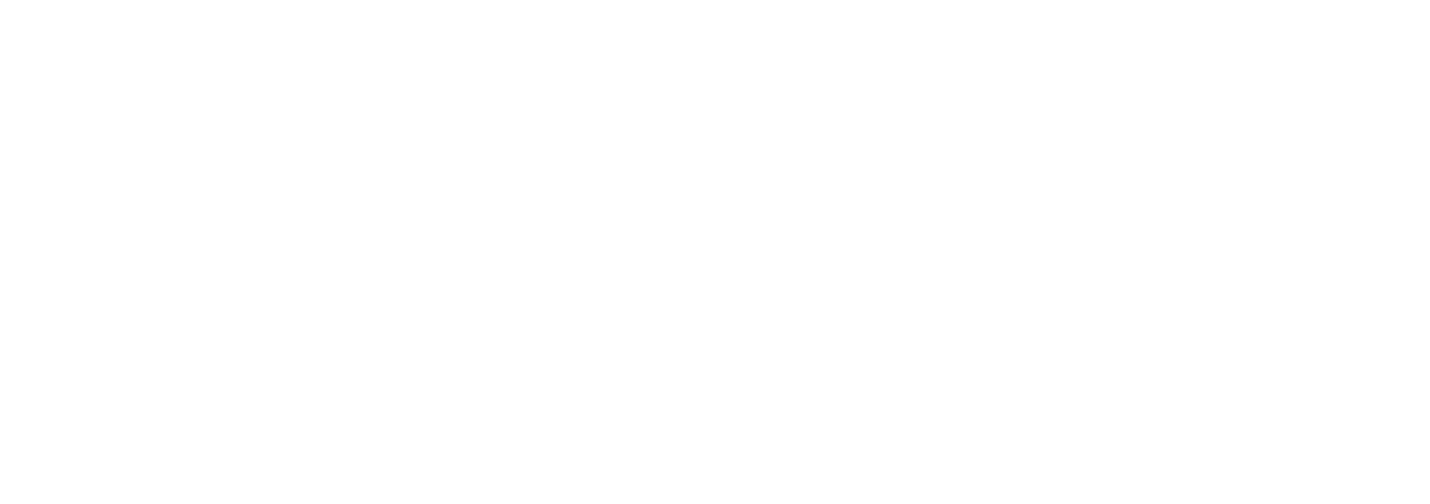

Group of Apache children as they arrived at Carlisle Indian School from Fort Marion, Florida, April 30, 1887. © Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Group of Apache boys and girls at the Carlisle Indian School, 1891. © Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Pueblos from Laguna, New Mexico who entered Carlisle Indian School on July 31, 1880. Left to right Mary Perry (standing), John Menaul, Benjamin Thomas. © Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Left to right: John (Menaul) Chaves, Mary Perry, Benjamin Thomas after they had been at the school for some time. They returned to their homes on June 17, 1884. © Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Zie-wie Davis, Sioux at age 15, on her arrival at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Hampton, Virginia, c. 1878. Hampton University Archives.

Zie-wie Davis, Sioux, a photo taken while she was at the Institute. Hampton University Archives.

Student Readings

Reading 1

Ota Kte (Luther Standing Bear, a Lakota Sioux), who became well known as an author and spokesperson for his people in the early 1900s, was one of the first of his generation to be sent to a boarding school.

At that time I thought nothing of it, but now I realize that I was the first Indian boy to step inside the Carlisle Indian School grounds. Here the girls were all called to one side by Louise McCoz, the girls’ interpreter. She took them into one of the big buildings, which was very brilliantly lighted, and it looked good to us from the outside…

But the room we entered was empty. A cast iron stove stood in the middle of the room, on which was placed a coal oil lamp. There was no fire in the stove. We ran through all the rooms, but they were all the same — no fire, no beds. This was a two-story building, but we were all herded into two rooms on the upper floor.

Well, we had to make the best of the situation, so we took off our leggings and rolled them up for a pillow. All the covering we had was the blanket we each had brought. We went to sleep on the hard floor, and it was cold. We had been used to sleeping on the ground, but the floor was so much colder.

Next morning we were called downstairs for breakfast. All we were given was bread and water. How disappointed we were. At noon we had some meat, bread, and coffee, so we felt a little better. But how lonesome the big boys and girls were for their faraway Dakota homes where there was plenty to eat!

The big boys seemed to take it worse than we smaller chaps did. I guess we little fellows did not know any better. The big boys would sing brave songs, and that would start the girls to crying. They did this for several nights. The girls’ quarters were about 150 yards from ours, so we could hear them crying. After some time the food began to get better, but it was far from being what we had been used to receiving back home.

* * *

I was thrust into an alien world, into an environment as different from the one into which I was born as it is possible to imagine, to remake myself as if I could into the likeness of the invader.

From Luther Standing Bear, My Indian Boyhood (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988).

Reading 2

An anonymous Santa Clara Pueblo woman recalls the day she was taken to the Santa Fe Indian School, as a five-year-old in 1915.

I remember it was in October and we had a pile of red chile and we were tying chiles into fours. And then my grandfather was putting them on a longer string. We were doing that when they came to get me. Then right away my grandma and my mother started to cry. “Her? She’s just a little girl! She’s just a little girl, you can’t take her.”

“But we have to take somebody. We can’t take your grandson, so we have to take your granddaughter….”

The next day my mother sent me…to the relatives’ houses to be blessed, where they are always sending us when we are leaving our village. They used to send us to relatives to be blessed so that the Creator can take care of us when we are away from our families….

My mother put her best shawl on me. It was getting a little chilly. It was late. Pretty soon the train whistled around the bend near the Rio Grande and it came. I was already five years old, but my grandpa was holding me on his knee. So when the train came, I got in. I saw the tears coming out of that brave man, my grandpa who was so brave and strong.

I can still picture my folks to this day, just standing there crying, and I was missing them….

From Joseph Bruchac, Lasting Echoes: An Oral History of Native American People (New York: Avon Books, Inc., 1997), p. 90.

Reading 3

Zitkala-Sa, in her widely read series of magazine articles, described the sad experience of being separated from her home and tribe.

“Like a slender tree, I had been uprooted from my mother, nature, and God,” she wrote. “I was shorn of my branches, which had waved in sympathy and love for home and friends.”

From Michael L. Cooper, Indian School: Teaching the White Man’s Way (New York: Clarion Books, 1999), p. 93.

Reading 4

Ohiyesa, whose name had been changed to Charles Eastman, described his frustration in learning English.

“…we youthful warriors were held up and harassed with words of those letters. Like raspberry bushes in the path, they tore, bled, and sweated us those little words like rat, eat, and so forth until not a semblance of our native dignity and self-respect was left.”

From Michael L. Cooper, Indian School: Teaching the White Man’s Way (New York: Clarion Books, 1999), pp. 52, 54.

Reading 5

Many Native Americans fiercely opposed sending their children to any of the government schools. White authorities responded to their resistance with force and trickery.

“Everything in the way of persuasion and argument having failed,” reported one BIA [Bureau of Indian Affairs] agent, “it became necessary to visit the camp unexpectedly with a detachment of police, and seize such children as were proper and take them away to school, willing or unwilling.”

. . . Indian school officials disciplined students in many different ways. Teachers often used shame or embarrassment as punishment. A boy caught sneaking food out of the dining room had to stand on a chair in the middle of the room during dinner. A girl who wet her bed had to carry a mattress for a day…. Another punishment was hard labor. “If you had done something extremely out of line, you worked on the rock pile on Saturday,” one boy said of the dreaded sentence. . . “That was brutal work. It was like being in prison.”

From Michael L. Cooper, Indian School: Teaching the White Man’s Way (New York: Clarion Books, 1999), pp. 28, 48, 49.

Resistance Readings

[At Fort Mojave School in Arizona, students as young as seven- and eight-years-old were locked up as punishment for running away.]

After locking up several runaways, one teacher recalled, she heard the loud sound of smashing wood. She went to investigate. “At the sturdy jail, there lay the sturdy door, broken from its hinges. There lay the log, a big one, and the many pieces of rope. We were amazed.” The children had made handles from the rope and used the log as a battering ram to break down the jail door and free those inside.

* * * *

Two Carlisle girls tried to burn down their dormitory. They set newspapers on fire in the reading room and then hurried to join the other pupils at dinner. The blaze was quickly discovered and extinguished. Later that day, the two [students] tried again. They filled a pillowcase with paper, lit it, and tossed the flaming bundle into a closet. The blaze was also quickly discovered and put out…. The pair were arrested, tried, and sentenced to 18 months in the Pennsylvania women’s penitentiary.

From Michael L. Cooper, Indian School: Teaching the White Man’s Way (New York: Clarion Books, 1999), p. 48.

Additional Resources

FILM

Rabbit-Proof Fence. Set in Australia, this film is based on a true story. The Australian government employed practices with the aboriginal children that were similar to U.S. government practices with Native Americans. In the film, three young girls escape from a boarding school and make a perilous 1,200-mile journey back to their home. Highly recommended for high school students and adults, this film dramatically portrays the kidnapping of children from their parents, the concerted efforts of Indigenous communities to protect their children, the government’s perspective and its tactics, and the resilience and resistance of the children.

BOOKS

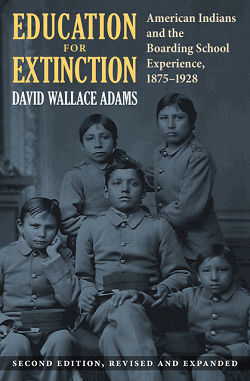

Adams, David Wallace. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience 1875-1928. University Press of Kansas, 2020. A detailed account of the day-to-day lives of Indigenous youth inside an institution, along with resistance efforts to escape.

Cooper, Michael L. Indian School: Teaching the White Man’s Way. Clarion Books, 1999. An upper-elementary and middle-school book with extensive photos. There are a few comments that probably reflect the European-American background of the author; however, it is overall a very useful text.

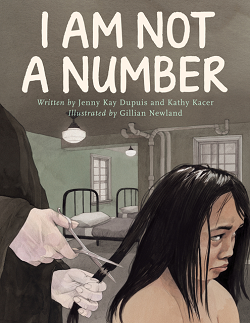

Dupuis, Jenny Kay and Kathy Kacer. I Am Not a Number. Second Story Press, 2016. For upper elementary students, the story of eight-year-old Irene, who, after dehumanizing treatment at the hands of the nuns in a residential school, returns home to her parents who refuse to send her or her brothers away again.

Jordan-Fenton, Christy and Margaret Jordan-Fenton. When I Was Eight. Annick Press, 2013. A picture book memoir of Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, who goes to an oppressive residential school to learn to read.

Robertson, David. When We Were Alone. Highwater Press, 2016. A picture book recounting a conversation between a grandmother and her granddaughter, as the elder recounts her youth in a residential school.

Santiago, Chiori. Home to Medicine Mountain. Children’s Book Press, 2002. An illustrated book for elementary school-aged children, based on the true story of two brothers who escaped from a Native American boarding school in the 1930s.

Standing Bear, Luther. My Indian Boyhood. Bison Books, 2006. For elementary students, the story of Standing Bear during his youth, as he learned be a warrior and a hunter, prior to his life at a residential school.

See also the American Indians / Indigenous Peoples / Native Nations booklist at SocialJusticeBooks.org.

© 2021 Teaching for Change

Reprint Permissions

© 1999 Clarion Books. Reprinted with permission from Michael L. Cooper, Indian School: Teaching the White Man’s Way (New York: Clarion Books, 1999).

The material reprinted from Joseph Bruchac, Lasting Echoes: An Oral History of Native American People (New York: Avon Books, Inc., 1997) is in the public domain.