Civil Rights Movement Mythbusters Quiz

Questions and Answers

Below are the questions and answers to our Civil Rights Movement Mythbusters Quiz.

Q1: Which of the following was the overarching goal of the Civil Rights Movement?

A: Equality, empowerment, and democracy

Memphis Sanitation Strike of 1968

Different leaders and activists often held differing views about both tactics and ultimate visions of a just society, and the evolution of the freedom struggle meant that people’s perspectives changed over time. But leaders as diverse as Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X realized that it would take fundamental economic, social, and political changes to create a United States in which all people were truly free.

Learn More

Putting the Movement Back into Civil Rights Teaching, “Teaching Eyes on The Prize: Teaching Democracy” by Judy Richardson.

Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years, 1954-1985 (Film). Produced by Henry Hampton. Blackside. 1987. Comprehensive documentary history of the Civil Rights Movement.

Q2: Who took steps to petition the United Nations Commission on Human Rights to investigate charges that the United States was violating not just the civil rights, but also the human rights, of African Americans?

A: Malcolm X

Malcolm X at the United Nations in 1963. Photo by Robert Haggins.

In July of 1964, Malcolm X attended the second meeting of the Organization of African Unity (OAU). He presented a petition asking,

In the interest of world peace, we beseech the heads of the independent African states to recommend an immediate investigation into our problem by the United Nations Commission on Human Rights.

According to UN procedures, a nation can request a human rights investigation of another country on behalf of the people whose rights have been violated.

The African heads of state discussed the proposition at the OAU summit but failed to bring the case before the UN based in part by pressure from the U.S. State Department. [Description from the Stanford Liberation Curriculum Project lesson called “Human Rights, By Any Means Necessary.”]

Learn More

Malcolm X: Message to the Grassroots read by Mos Def. From Voices of a People’s History of the United States.

Q3: The crucial element enabling progress in winning civil rights was:

A: Grassroots activism and organizing

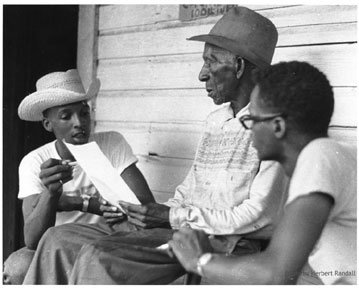

Doug Smith and Sandy Leigh participate in voter registration canvassing, 1964. Photo (c) Herbert Randall. McCain Library and Archives, USM.

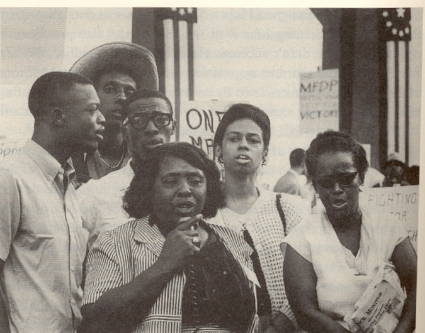

Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker address participants at a rally for the MFDP to be seated at the 1964 DNC. (AP Photo)

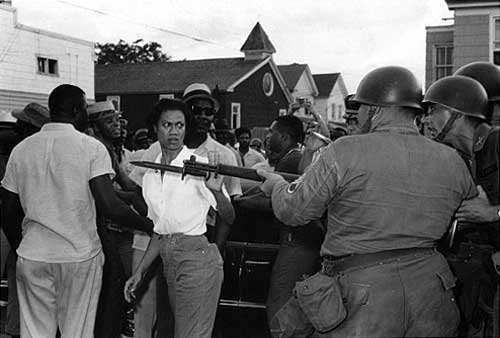

Gloria Richardson facing off the National Guard, Cambridge, Maryland, in May 1964. Photo by Fred Ward

CORE pickets Penny’s Department Store in Berkeley, Calif., December, 1963.

Inspiring leaders, large mass demonstrations, and eventually federal civil rights legislation and enforcement all contributed to changes toward greater equality, but grassroots organizers laid the essential foundation of the movement. Largely unacknowledged in textbooks, they performed the unglamorous, painstaking, and often dangerous work of building trust, commitment, and collective action toward local victories.

The publisher of I’ve Got the Light of Freedom, by Charles Payne, explains:

The leaders were ordinary women and men–sharecroppers, domestics, high school students, beauticians, independent farmers–committed to organizing the civil rights struggle house by house, block by block, relationship by relationship.

The young organizers who were the engines of change in the state were not following any charismatic national leader. Far from being a complete break with the past, their work was based directly on the work of an older generation of activists, people like Ella Baker, Septima Clark, Amzie Moore, Medgar Evers, Aaron Henry. These leaders set the standards of courage against which young organizers judged themselves; they served as models of activism that balanced humanism with militance.

While historians have commonly portrayed the movement leadership as male, ministerial, and well-educated, Payne finds that organizers in Mississippi and elsewhere in the most dangerous parts of the South looked for leadership to working-class rural Blacks, and especially to women. Payne also finds that Black churches, typically portrayed as front runners in the civil rights struggle, were, in fact, late supporters of the movement.

Learn More

I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. By Charles Payne. 2007. University of California Press. One of the best books on the day-to-day grassroots organizing that was the primary, though less visible, work of the Civil Rights Movement.

Standing on My Sisters’ Shoulders. Film. By Joan Sadoff, Robert Sadoff, and Laura Lipson. 2002. 60 minutes. A documentary film on women in the Civil Rights Movement. While focused on Mississippi, it is useful for shining on a light on the people’s history of the Movement and in particular the role of women.

Civil Rights Movement Veterans website. Created by Veterans of the Southern Freedom Movement (1951-1968), this is where (as they explain), “we tell it like it was, the way we lived it, the way we saw it, the way we still see it. With a few minor exceptions, everything on this site was written, created, or spoken by Movement activists who were direct participants in the events they chronicle.

Critical Focus: The Black and White Photographs of Harvey Wilson Richards. This book of photographs is available for free for teachers. These photos (such as the CORE photo above) depict the people’s history of the Civil Rights Movement and related struggles and demonstrate that racism and resistance were not limited to the southern states.

Q4: Which of the following is TRUE of Rosa Parks, the woman who helped spark the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955 after being arrested for defying the city’s bus segregation laws?

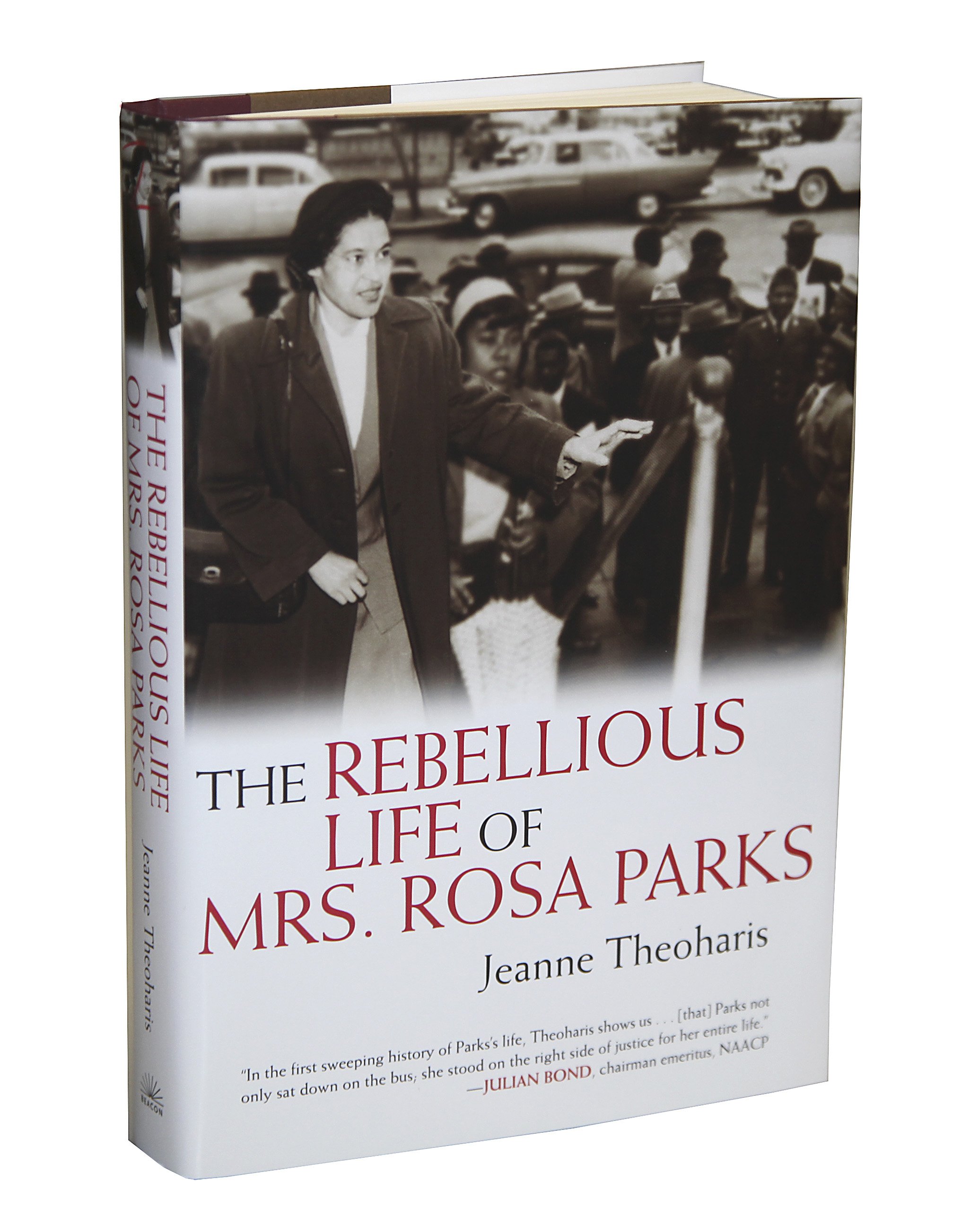

A: As Secretary of the local NAACP chapter and leader of its Youth Group, she had a long history of activism before her action that began the bus boycott.

At the time of the boycott, the 43-year-old Ms. Parks already had several run-ins with bus drivers because she opposed the law requiring African Americans to enter the bus from the back, yet pay in the front. In fact, the driver on December 1, 1955 who called the police had previously thrown her off the bus for refusing to enter through the back door. In addition to her NAACP activities, Ms. Parks was involved in trying to desegregate Montgomery’s schools and had attended an interracial meeting at Tennessee’s Highlander Folk Center, a social justice leadership training school that played a key role in the labor and Civil Rights Movements.

Learn More

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks. By Jeanne Theoharis. 2013. A revealing window into Parks’ politics and years of activism.

Putting the Movement Back into Civil Rights Teaching, pp. 25–31, “The Politics of Children’s Literature: What’s Wrong with the Rosa Parks Myth” by Herb Kohl.

Q5: After Rosa Parks was arrested, the Montgomery Bus Boycott was first set in motion when:

A: The Women’s Political Council, under the leadership of Jo Ann Robinson, distributed 35,000 leaflets urging 42,000 black residents of Montgomery to boycott public transportation.

The crucial roles of women, grassroots organizers, and rank-and-file citizens in the Civil Rights Movement are often minimized or left out of U.S. history books. Under the leadership of Jo Ann Robinson, a college English professor, the Montgomery Women’s Political Council began organizing against segregated buses in 1949. This lay the groundwork to mobilize the boycott quickly after Rosa Parks was arrested. NAACP leader and labor organizer E.D. Nixon bailed Ms. Parks out of jail and convened a meeting of ministers the first night of the boycott to provide leadership. At that meeting, the ministers formed the Montgomery Improvement Association and elected the 27-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. as its leader.

During the 381-day boycott, thousands of African Americans walked to work. The movement depended on the many people who organized fundraising activities, carpools, and coordinated taxi service.

King’s oratory and leadership helped sustain the movement, but its victory was built on the daily contributions of many unsung activists.

Learn More

Putting the Movement Back into Civil Rights Teaching, “Montgomery Bus Boycott—Organizing Strategies and Challenges” by Alana Murray.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It: The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1987.

Q6: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was killed in 1968, exactly one year to the day after he gave a speech on:

A: The Vietnam War

April 4, 1967. Dr. King at Riverside Church in NYC. Photo by John C. Goodwin.

On April 4, 1967, exactly one year before his assassination, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a speech in New York City on the occasion of his becoming co-chairperson of Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam (subsequently renamed Clergy and Laity Concerned).

Titled “Beyond Vietnam,” it was his first major speech on the war in Vietnam—what the Vietnamese aptly call the American War. King linked the escalating U.S. commitment to that war with its abandonment of the commitment to social justice at home. His call for a “shift from a ‘thing-oriented’ society to a ‘person-oriented’ society” and for us to “struggle for a new world” has acquired even greater urgency than when he issued it decades ago.

The speech concludes:

Our only hope today lies in our ability to recapture the revolutionary spirit and go out into a sometimes hostile world declaring eternal hostility to poverty, racism, and militarism. With this powerful commitment we shall boldly challenge the status quo and unjust mores and thereby speed the day when “every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low, and the crooked shall be made straight and the rough places plain …” Now let us begin. Now let us rededicate ourselves to the long and bitter—but beautiful—struggle for a new world.

[This description is from a Rethinking Schools article posted on the Zinn Education Project website.]

Learn More

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.: “Beyond Vietnam”. Film clip. Dr. Martin Luther King’s “Beyond Vietnam” (1967) speech is read by Michael Ealy. From Voices of a People’s History of the United States.

A Revolution of Values. Text of speech by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on the Vietnam War with teaching ideas. Zinn Education Project website.

There’s Infinitely More to Martin Luther King, Jr. Than ‘I Have a Dream.’ By Craig Gordon. Article about how Gordon introduces his high school students to the speeches and work of Dr. King beyond “I have a dream.”

Vietnam: An Antiwar Comic Book. By Julian Bond and illustrated by T. G. Lewis. 1967. 19 pages. A detailed history and analysis of the Vietnam War in an easy to read format. Reprinted in full in Putting the Movement Back into Civil Rights Teaching.

Q7: What role did the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) most consistently play with regards to the Civil Rights Movement?

A: They collected information, spied on civil rights leaders (including Martin Luther King, Jr.), and spread misinformation.

The FBI, under J. Edgar Hoover, had a long history of investigating organized efforts by African Americans, including the 1940s March on Washington Movement.

As described the NPR interview with Tim Weiner (author of Enemies: A History of the FBI):

“Hoover saw the civil rights movement from the 1950s onward and the anti-war movement from the 1960s onward, as presenting the greatest threats to the stability of the American government since the Civil War,” he says. “These people were enemies of the state, and in particular Martin Luther King [Jr.] was an enemy of the state. And Hoover aimed to watch over them. If they twitched in the wrong direction, the hammer would come down.”

In the fall of 1963, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy approved wiretaps on all of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s telephones. The FBI even wrote threatening letters to King with the aim of coercing King to step down from his position as the head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

James W. Loewen notes in Lies My Teacher Told Me: “In August 1963 Hoover initiated a campaign to destroy Martin Luther King, Jr., and the civil rights movement. With the approval of Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, he tapped the telephones of King’s associates, bugged King’s hotel rooms, and made tape recordings of King’s conversations with and about women. The FBI then passed on the lurid details, including photographs, transcripts, and tapes, to Sen. Strom Thurmond and other white supremacists, reporters, labor leaders, foundation administrators, and, of course, the president…King wasn’t the only target: Hoover also passed on disinformation about the Mississippi Summer Project; other civil rights organizations such as CORE and SNCC; and other civil rights leaders, including Jesse Jackson.”

Learn More

Why We Should Teach About the FBI’s War on the Civil Rights Movement by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca.

Tracked in America. This website explores the historical context and stories of individuals who have been targets of U.S. government surveillance during the 20th century. It includes timelines, interviews, and primary documents. National Security Archive. Online access to declassified U.S. documents.

Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH) Sovereignty Commission Archive. All the documents from the Sovereignty Commission (an agency created by the state government to spy on and undermine the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi) are now online.

Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. By James W. Loewen. (Touchstone, 2007).

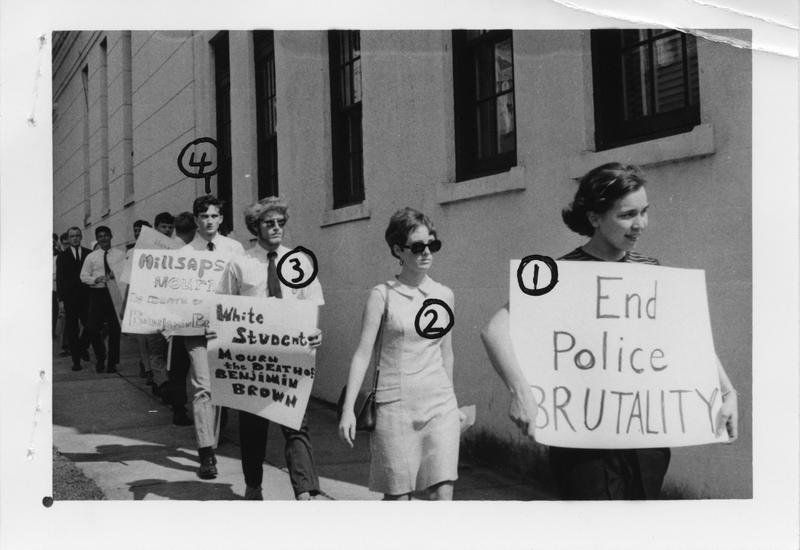

Millsaps students protesting the death of JSU student and civil rights worker Benjamin Brown. Photo shot by the Commission with numbers identifying individual students.

Q8: During most of the 20th century, African Americans were prevented from voting by:

A: All of the above

LEFT: A. Philip Randolph at the Freedom School Convention in Meridian, Miss. RIGHT: Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, Lauderdale County Meeting at First Union Baptist Church, Meridian. Both photos by Mark Levy.

After the Civil War, many African Americans took grave risks to exercise the right to vote, encountering relentless and multifaceted white resistance. While there were important pockets of black voting strength in the South (primarily in urban areas) during Reconstruction, it was not until the mid-1960s that the Civil Rights Movement was able to decisively turn the tide against black disenfranchisement.

One of the best ways to learn about the grassroots work of the Civil Rights Movement is to read the accounts of voter registration campaigns, including the role of Freedom Schools. Here one can learn about the strength and determination of the people who risked their lives to exercise their legal right to vote.

Learn More

“SNCC: The Battle-Scarred Youngsters.” A report from the front lines of the civil rights battle in Greenwood, Mississippi–a very dangerous place to be. By Howard Zinn in The Nation, October 5, 1963. Written in response to the March on Washington, this article provides chilling interviews with young activists who had been jailed for promoting the democratic practice of voting. Read online.

On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Trail. By Charles E. Cobb, Jr. A useful reference to find the history of the freedom struggle in communities across the United States.

Civil Rights Movement Veterans website. This website is created by Veterans of the Southern Freedom Movement (1951-1968). It is where, as they explain, “we tell it like it was, the way we lived it, the way we saw it, the way we still see it. With a few minor exceptions, everything on this site was written, created, or spoken by Movement activists who were direct participants in the events they chronicle.

Education and Democracy. An online description of the role of Freedom Schools in the campaign for voting rights. Includes full Freedom School curriculum.

Q9: During the 1960s a free breakfast program for children in Oakland, CA was sponsored by:

A: The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense

During the 1960s, the Black Panther Party’s provocative rhetoric of armed self-defense often led to demonized representations of them as a violent group. The BPP actually presented a progressive party platform, which quotes the Declaration of Independence and advocates free health care for the poor, full employment, decent housing, and an end to police brutality. Projects like the Free Breakfast Program reflected the Panthers’ commitment to community service and organizing.

Learn More

The Black Panther Party Reconsidered. Edited by Charles E. Jones. Baltimore, Md.: Black Classic Press, 1998.

The Black Panthers Speak. By Philip S. Foner. Chicago: Haymarket Press, 2014.

Putting the Movement Back into Civil Rights Teaching

Pp. 36–37, The Black Panthers and Community Control. Brief excerpt on the Panther Party and their push for democracy and community control.

Pp. 149, “What We Want,” by Kwame Toure (Stokely Carmichael)

Pp. 145, LESSON: “The Black Panther Party Legacy and Lessons for the Future” by Debbie Wei.

Pp. 153, LESSON: “‘What We Want, What We Believe’: Teaching with the Black Panthers’ Ten Point Program” by Wayne Au.

Q10: In addition to African Americans, what other groups were fighting for equal rights and/or self-determination in the 1960s and 1970s?

A: All of the above

Muhammad Ali, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Floyd Red Crow Westerman, Harold Smith, Stevie Wonder, Marlon Brando, Max Gail, Dick Gregory, Richie Havens, and David Amram at the concert at the end of the Longest Walk, a 3,600-mile protest march from San Francisco to Washington, D.C., in 1978 in the name of the Native rights. Photo: David Amram.

Too often history is taught as segmented, isolated incidents in time. Traditionally, the Civil Rights Movement is viewed solely as a struggle for black Americans, by black Americans. Actually, the Civil Rights Movement was a struggle for full democracy for everyone in the U.S. Vincent Harding noted in “Black History IS America’s History” (1990), that:

One of the major challenges available to teachers in every possible institution is to introduce ourselves and our students to an alternative vision of the movement, to see it as a great gift for all Americans, as a central point of grounding for our own pro-democracy movement.

The modern Civil Rights Movement also inspired oppressed people nationally and internationally. As Bernice Johnson Reagon explains:

Few movements have created as many ripples [as the Civil Rights Movement], and certainly not ripples that crossed racial and class and social lines as happened in the 1960’s.

The Civil Rights Movement, being Black at the bottom, offered up the possibility of a thorough analysis of society…. The exciting thing about the Civil Rights Movement is the extent to which it gave participants a glaring analysis of who and where they were in society… People who were Spanish-speaking in the Civil Rights Movement, who had been white, when they got back, turned Brown. Some of the leaders of the antiwar movement were politicized by their work in the Civil Rights Movement…. The Civil Rights Movement was only a dispersion. Its dispersion continues to be manifested in ever-widening circles of evaluation of civil and human rights afforded by this society.

…You cannot present an accurate picture of the movements of the 1960’s and 1970’s unless you show them resting on the foundation of the Civil Rights Movement. A study that’s done from some other point of view will be a myopic report on those other movements. I find, generally, that people who participated in those other movements, especially if those other movements were predominately white, see whatever they participated in as central… It is, again, a distortion of what Black people do to stimulate the salvation of this country… My point is the Civil Rights Movement [bore] not just the Black Power Movement and Black revolutionary movements, but every progressive struggle that has occurred in this country since that time.” [In an interview with Dick Cluster called “The Borning Struggle: The Civil Rights Movement,” South End Press, reprinted in Putting the Movement Back into Civil Rights Teaching.]

Learn More

Putting the Movement Back Into Civil Rights Teaching: A Resource Guide for Classrooms and Communities. By Deborah Menkart, Alana Murray, Jenice L. View. 2004. Teaching for Change and PRRAC. “One of the only curricula to connect the Civil Rights Movement to the struggles of Native Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and women. It’s an incredible tool not just for teaching history, but also for teaching students to take up the legacy these movements helped to create.” —Ariana Quiñones, Deputy Vice President for Education, National Council of La Raza

Walkout. Film produced by Moctesuma Esparza. 2006. 111 minutes. The true story of the Chicano students of East L.A., who in 1968 staged several dramatic walkouts in their high schools to protest academic prejudice and dire school conditions.

Alcatraz is Not an Island. Website on the history of the 19-month occupation of Alcatraz by Indians of All Nations.

We Took the Streets: Fighting for Latino Rights with the Young Lords. By Miguel Melendez. 2003. Legacy of the Young Lords in the Puerto Rican struggle for equality and independence.

Teaching resources: Lesson, books, films, and articles for K-12 can be found on the Zinn Education Project website.

If you like this quiz, make a donation to Teaching for Change so that we can continue to develop and share resources on the Civil Rights Movement. Contact Teaching for Change with corrections and/or additions.

This Quiz was developed by Jennifer Arrington and David Levine. Updated by Neha Singhal.

© Teaching for Change