March on Washington Hidden History Quiz

When most people think of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, what comes to mind is Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic statement, “I Have a Dream.” In truth, there was much more to this historic event than these four words in King’s speech.

The March on Washington was a milestone in a movement that spanned many years of activism, organizing, and civil disobedience by a wide variety of civil rights’ groups. The date of the march itself symbolizes that long history — the March on Washington was held on the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) and eight years to the day after 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi (Aug. 28, 1955).

Teaching for Change designed this quiz about the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom to challenge assumptions, deepen understanding, and inspire further learning. Please take the quiz, share it, and send us your feedback.

Questions and Answers

Below are the questions and answers to our March on Washington Hidden History Quiz.

Q1: Was the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom the first national demonstration in Washington, D.C., led by civil rights organizations?

A: No, there were multiple national demonstrations by civil rights organizations in Washington, D.C.

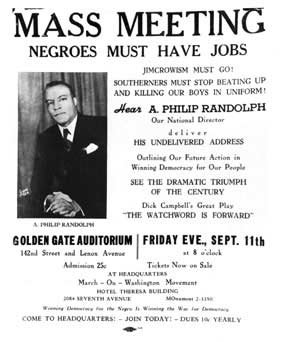

A. Philip Randolph founded the March on Washington Movement, a movement that was started in the early 1940s with the aim of desegregating the arms manufacturing industry during World War II. Members of the March on Washington Movement planned for a national demonstration in Washington, D.C. in 1941, but called it off after President Roosevelt issued an executive order banning segregation in the arms industry. Roosevelt issued the order after a meeting with Randolph where he became convinced that Randolph could pull off the march, which threatened to bring 100,000 black people to Washington, DC, using civil disobedience to shut down the city.

In October of 1958, 10,000 people marched in Washington, D.C. as part of the Youth March for Integrated Schools. Harry Belafonte, renowned performer and activist, led a group of students during the march to picket at the White House. They intended to speak with President Eisenhower, but were denied access and instead left behind a list of demands for the president.

The following year another national youth march was organized, this time bringing out 26,000 people. Key organizers included Martin Luther King, Jr. Jackie Robinson, Ruth Bunche, Daisy Bates, Roy Wilkins, and Charles Zimmerman.

Learn More

Youth March for Integrated Schools. Article online at the Martin Luther King, Jr., Research & Education Institute.

Letter (1959) to Student Leaders re Youth March. Primary document online on the CRMvet.org website.

March on Washington Movement. Article online at BlackPast.org.

Eyes on the Prize: No Easy Walk. Video online.

Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America. By Lerone Bennett (Johnson, 2007).

Q2: How long before the event did the six major civil rights organizations meet and agree to organize the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom together?

Answer: Two months

The original plan for the March on Washington was outlined by organizer Bayard Rustin in January of 1963 and soon adopted by the Negro American Labor Council (NALC). Throughout the spring of 1963, more organizations pledged their support for the march, including the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Initially, two of the largest civil rights organizations, the NAACP and the Urban League, didn’t support the March.

It wasn’t until July 2, less than two months before the date of the march, that six of the major civil rights organizations met and agreed to organize the march together.

The fact that the march could be organized so quickly was due to multiple factors including the groundwork established since 1941 by A. Philip Randolph; the planning begun in January of 1963 by Rustin and the Negro American Labor Council (NALC); Rustin’s skills as an organizer; and decades of grassroots organizing all over the country.

Fifteen hundred community-based organizations — churches, unions, women’s groups, youth groups, and other civil rights organizations — helped to organize, recruit, arrange transportation, and raise funds for the March on Washington. At least 50,000 participants were brought by churches alone and unions brought almost as many.

The participation of roughly 250,000 people was a product of the history and collaboration of countless community based and national organizations.

Learn More

The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights. By William P. Jones (Norton, 2013).

This Is the Day: The March on Washington. Photographs by Leonard Freed. Text by Michael Eric Dyson, Julian Bond, and Paul Farber. (Getty Publications, 2013).

Reuther Library. Photo archives of Wayne State University Dep’t. of Labor and Urban Affairs.

Q3: The March on Washington had a list of 10 demands. How many of those demands were about labor issues?

Answer: Five

Five of the March on Washington demands focused on labor issues, including a minimum wage act and a call for jobs for the unemployed. The organizers knew that full civil and human rights for African Americans depended on access to jobs, education, housing, and health care.

In addition to the churches, religious organizations, and civil rights organizations involved in the march, the United Automobile Workers (UAW) and the Negro American Labor Council sponsored and helped organize the march. One of the main organizers of the March on Washington, who was also the founder of the March on Washington Movement, A. Philip Randolph, was a labor leader who helped found the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

Other demands addressed education, housing, voting, public accommodations, and all constitutional rights. Some key issues not addressed in the demands included widespread violence against African Americans; targeted brutality and vigilantism against any people of color (and white allies) attempting to exercise their civil rights; women’s rights; and the Vietnam War.

Learn More

A. Philip Randolph Institute

The full list of demands of the March on Washington.

The Unknown Origins of the March on Washington: Civil Rights Politics and the Black Working Class. Article online by William P. Jones in Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas, Volume 7, Issue 3.

Resources for teaching about labor history from the Zinn Education Project website.

Q4: Daisy Bates, an NAACP organizer in Little Rock, Ark., was one of two women to speak (briefly) at the 1963 March on Washington. Although neither was on the program as a speaker, who was the other woman who spoke that day?

From left to right: Daisy Bates, Diane Nash Bevel, Rosa Parks, Gloria Richardson

A: Josephine Baker, singer, dancer, and member of the French Resistance.

Josephine Baker at the March on Washington, 1963

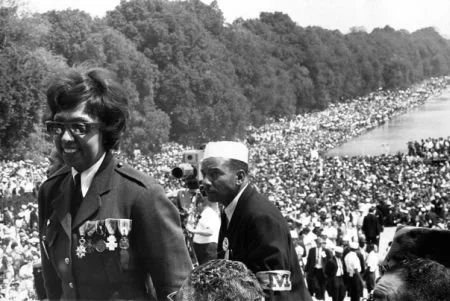

While both Daisy Bates and Josephine Baker spoke, neither was listed as a speaker on the official program and neither were allowed to speak for long. This absence of women’s voices was a stark contrast to the central role that women played in the Civil Rights Movement, and in the preparations for the March on Washington in particular.

As Jeanne Theoharis wrote in The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks: “As magnificent as the day was, the lack of recognition for women’s roles was readily apparent, and Rosa Parks was increasingly disillusioned by it. No women had been asked to speak. Pauli Murray had written A. Philip Randolph criticizing the sexism. Anna Hedgeman had also objected. Dorothy Height, president of the National Council of Negro Women, pressed for a more substantive inclusion of women in the program. Their criticisms were rebuffed.” Instead, as Theoharis explained, “a ‘Tribute to Women’ would highlight six women — Rosa Parks, Gloria Richardson, Diane Nash, Myrlie Evers, Mrs. Prince Lee, and Daisy Bates — who would be asked to stand up and be recognized by the crowd. Daisy Bates introduced the tribute to women, a 142-word introduction written by John Morsell that provided an awkwardly brief recognition of women’s roles in the struggle for civil rights. . . .” (Listen to Bates’ speak, type “Bates” in search bar to Sync.)

Learn More

Josephine Baker’s full greetings on BlackPast.org.

Audio and transcription of Daisy Bates’ comments.

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks. By Jeanne Theoharis. (Beacon, 2013).

Women Make History: An Untold Story of the Civil Rights Movement. Lesson designed to introduce students in grades 7+ to women of the Civil Rights Movement and other movements for social justice.

Hands On the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC. Edited by Faith S. Holsaert, Martha Prescod Norman Noonan, Judy Richardson, Betty Garman Robinson, Jean Smith Young, and Dorothy M. Zellner (University of Illinois Press, 2010). This book includes a detailed description by Cambridge, Maryland activist Gloria Richardson of her experiences before and during the march.

Q5: The main organizer of the March on Washington, Bayard Rustin, has been omitted from much of the Civil Rights Movement’s history for which of the following reasons:

Bayard Rustin at the blackboard. Also see this collection of photos and primary documents from the Rustin Estate.

A: All of the above.

Bayard Rustin was a lifelong activist and political organizer. When Bayard was a child, his family was politically active in the NAACP and organized against Jim Crow. When Rustin went to college in New York City in the 1930s, he joined the Youth Communist League and organized with the campaign to free the Scottsboro Nine. Rustin later joined the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and the pacifist organization the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR).

During World War II Rustin, a pacifist, refused induction into the military. As Larry Brimner explains in We Are One:

[Bayard Rustin] informed the draft board that he could not report for either military duty or public service and explained that his reason for refusing all stemmed “from the basic spiritual truth that men are brothers in the sight of God.” What followed was federal prison in Ashland, Kentucky, where authorities regretted every minute of Bayard’s presence. No sooner had he arrived in prison to serve his three-year sentence than Bayard began staging protests. He protested segregation in the prison system. He protested prisoners’ living conditions. And he continued to study Gandhi. Prison officials begged for his transfer.

Rustin was also a gay man and when his sexual orientation was revealed, he was fired from his position at FOR. Rustin then began working with the War Resisters League and went on to help organize the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the March on Washington with Martin Luther King Jr.

For nearly six decades Rustin organized and protested against injustice. But despite his amazing work in the Civil Rights Movement, he is often erased from history because he had been a communist, a war resister and because he was gay.

In the past year, Rustin has finally begun to receive some of the long-overdue recognition he deserves, including the Medal of Freedom, posthumously awarded by President Obama in 2013.

Learn More

We Are One: The Story of Bayard Rustin. By Larry Dane Brimner. (Calkins Creek, 2007). For middle school.

Pacifism and the American Civil Rights Movement: A Celebration of the Centennial of Bayard Rustin (1912-2012). Primary documents and photos online.

Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin. Produced by Nancy Kates and Bennett Singer. 2002. 83 min. Documentary about the life of peace, labor, and civil rights activist Bayard Rustin.

I Must Resist: Bayard Rustin’s Life in Letters. Edited by Michael G Long. (City Light Books, 2012).

Q6: Which African American writer and/or leader, from the list below, was at the the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom but is not well known as having been there?

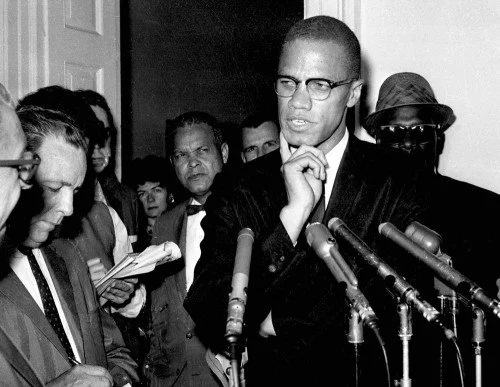

Answer: Malcolm X

Malcolm X was the charismatic leader of the Nation of Islam (NOI) who advocated Black self-determination. Elijah Muhammad, the head of the NOI, forbade members of the NOI from attending the March of Washington and Malcolm X called it the “farce on Washington.” Despite Elijah Muhammad’s orders, Malcolm X attended the March on Washington, speaking to the press about his opposition to the March, while speaking in private with a number of civil rights leaders.

As to the other people mentioned as possible answers:

W. E. B. DuBois, the African American intellectual leader and founder of the NAACP, died the night before the March on Washington in Ghana. As Charles Euchner explains in Nobody Turn Me Around: A People’s History of the 1963 March on Washington:

Western Union had delivered hundreds of telegrams of congratulations to the March on Washington tent. One came from W. E. B. Du Bois.

“One thing alone I charge you, as you live, believe in Life!” Du Bois said in a final message composed two months before, during his final illness. “Always human beings will live and progress to greater, broader and fuller life. The only possible death is to lose belief in this truth simply because the Great End comes slowly, because time is long.”

Then came the news that Du Bois had died the day before in Accra, Ghana, at the age of ninety-five. Maya Angelou led a group of Americans and Ghanaians to the U.S. embassy in Accra, carrying torches and placards reading “Down with American Apartheid” and “America, a White Man’s Heaven and a Black Man’s Hell.”

In Washington, the news fluttered through the audience and onto the platform. Continue reading to learn about the debate at the 1963 March on Washington as to who should announce the death of DuBois.

Ella Baker, 1968. AP photo.

Ella Baker was not present. If you have not heard of her before, please pause to read this short bio. Why? Because Baker was, as described in her biography by Barbara Ransby, “one of the most important African American leaders of the twentieth century and perhaps the most influential woman in the civil rights movement. Baker was a gifted grassroots organizer whose remarkable career spanned fifty years and touched thousands of lives. She was a key figure in the NAACP, a founder of the SCLC, and a prime mover in the creation of SNCC.”

Langston Hughes — poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist — was in Europe at the time of the 1963 March on Washington.

Learn More

Malcolm X: Message to the Grass Roots. Speech delivered on Nov. 10, 1963. Read by Mos Def. From Voices of a People’s History of the United States. Debates by Malcolm X and Bayard Rustin. “Separation or Integration” held in NYC on January 23, 1962, moderated by Rev. Donald Harrington, sponsored by Liberation Magazine and the War Resisters League. See a clip online. “A Choice of Two Roads” (moderated by John Donald), order from Pacifica Archives.

Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America. By Peniel E. Joseph. (Holt & Co., 2007). Scholar Peniel E. Joseph challenges the traditional narrative that portrays the Black Power Movement as the evil twin of the Civil Rights Movement while oversimplifying the Civil Rights Movement and treating the Black Power Movement as “too hot to touch.”

Q7: Was this the first time Martin Luther King Jr. gave a speech invoking the now famous phrase “I Have a Dream?”

A: No, Martin Luther King Jr. used that phrase before, including in a speech in Detroit two months earlier declaring, “I Have a Dream.”

On June 23, 1963, roughly two months before the March on Washington, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at the Walk to Freedom in Detroit, Michigan. The Walk to Freedom was the largest civil rights demonstration to date with 125,000 people marching for an end to police brutality and segregation in the South and for access to housing, education, and better wages in the North.

Martin Luther King Jr. said:

I have a dream this afternoon that one day right here in Detroit, Negroes will be able to buy a house or rent a house anywhere that their money will carry them and they will be able to get a job. Yes, I have a dream this afternoon that one day in this land the words of Amos will become real and ‘justice will roll down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.’

Learn More

Full transcript, online, of Martin Luther Kings Jr.’s speech at the Walk to Freedom in Detroit.

The Speech: The Story Behind Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Dream. By Gary Younge (Haymarket Press, 2013).

A Revolution of Values. The text of a speech by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on the Vietnam War, on the Zinn Education Project website.

Q8: How was the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) involved in the lead up to the March on Washington?

A: They collected information, spied on civil rights leaders (including Martin Luther King, Jr.), and spread misinformation.

The FBI, under J. Edgar Hoover, had a long history of investigating organized efforts by African Americans, including the earlier March on Washington Movement.

As described the NPR interview with Tim Weiner (author of Enemies: A History of the FBI):

Hoover saw the civil rights movement from the 1950s onward and the anti-war movement from the 1960s onward, as presenting the greatest threats to the stability of the American government since the Civil War.

These people were enemies of the state, and in particular Martin Luther King was an enemy of the state. And Hoover aimed to watch over them. If they twitched in the wrong direction, the hammer would come down.

In the fall of 1963, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy approved wiretaps on all of Martin Luther King Jr.’s telephones. The FBI even wrote threatening letters to King with the aim of coercing King to step down from his position as the head of the SCLC.

James W. Loewen notes in Lies My Teacher Told Me:

In August 1963 Hoover initiated a campaign to destroy Martin Luther King Jr., and the civil rights movement. With the approval of Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, he tapped the telephones of King’s associates, bugged King’s hotel rooms, and made tape recordings of King’s conversations with and about women.

The FBI then passed on the lurid details, including photographs, transcripts, and tapes, to Sen. Strom Thurmond and other white supremacists, reporters, labor leaders, foundation administrators, and, of course, the president . . . King wasn’t the only target: Hoover also passed on disinformation about the Mississippi Summer Project; other civil rights organizations such as CORE and SNCC; and other civil rights leaders, including Jesse Jackson.

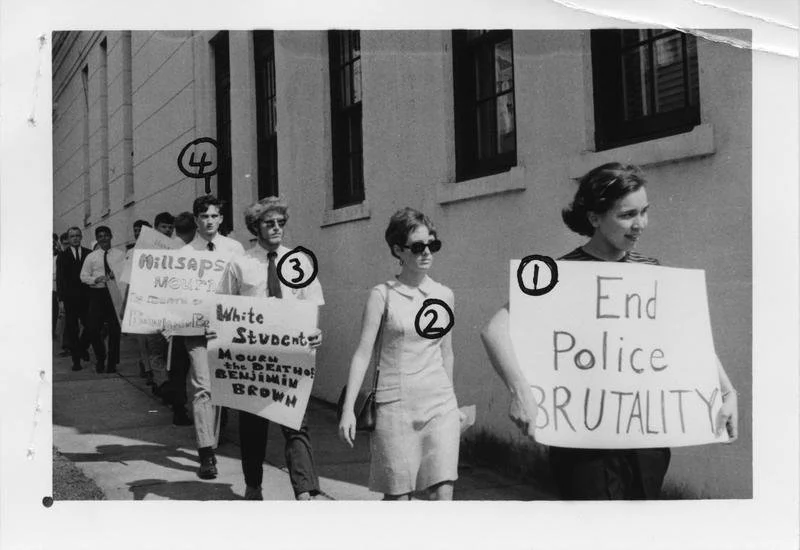

Millsaps students protesting the death of JSU student and civil rights worker Benjamin Brown. Photo shot by the Commission with numbers identifying individual students.

Learn More

Tracked in America. This website explores the historical context and stories of individuals who have been targets of U.S. government surveillance during the 20th century. It includes timelines, interviews, and primary documents.

National Security Archive. Online access to declassified U.S. documents.

Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH) Sovereignty Commission Archive. All the documents from the Sovereignty Commission (an agency created by the state government to spy on and undermine the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi) are now online.

Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. By James W. Loewen. (Touchstone, 2007).

Q9: Organizers of the March on Washington asked which speaker to leave out some of the radical content from his organization’s speech?

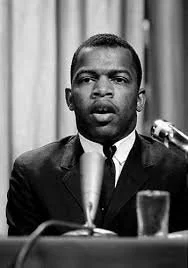

A: John Lewis, Chairperson, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

John Lewis was the chairperson of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a youth civil rights organization that fought on the frontlines to dismantle Jim Crow in the United States. Members of SNCC helped write the speech Lewis planned to give.

Some of the March on Washington leaders were uncomfortable with some of what they considered the radical content of the SNCC speech and asked Lewis to change it. The original speech included reference to the “Black masses,” “revolution,” and called the Kennedy administration’s Civil Rights bill “too little, too late.”

Lewis and other SNCC staff agreed to make changes in the speech, mainly because of their respect for Mr. Randolph, who expressed his strong desire that the march does not fall apart because of internal discord.

Learn More

Full text of the original version of John Lewis’ SNCC speech

Full text of the edited version of John Lewis’ SNCC speech

Eyes on the Prize: No Easy Walk. Video online. Includes an interview with SNCC veteran Courtland Cox about the request to change the speech.

Q10: Protesters came to the March on Washington to challenge racism in which region(s) of the United States?

A: All of the above.

As Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham explains in the preface to Freedom North: Black Freedom Struggles Outside the South, 1940-1980:

The civil rights movement occupies a prominent place in popular thinking and scholarly work on post-1945 U.S. history. Yet the dominant narrative of the movement remains that of a nonviolent movement born in the South during the 1950s that emerged triumphant in the early 1960s, only to be derailed by the twin forces of Black Power and white backlash when it sought to move outside the South after 1965.

African American protest and political movements outside the South appear as ancillary and subsequent to the “real” movement in the South, despite the fact that black activism existed in the North, Midwest, and West in the 1940s, and persisted well into the 1970s. [In fact, there were] distinctive forms of U.S. racism according to place and a variety of tactics and ideologies that community members used to attack these inequalities. [T]he civil rights movement was indeed a national movement for racial justice and liberation.

Learn More

Freedom North: Black Freedom Struggles Outside the South, 1940-1980. Edited by Jeanne F. Theoharis and Komozi Woodard. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project. An online archive of primary documents for teaching about the civil rights and labor history of Seattle.

’63 Boycott. A website and film chronicling the Chicago Public School Boycott of 1963 when more than 200,000 Chicagoans, mostly students, marched to protest the segregationist policies of CPS Superintendent Benjamin Willis, who placed mobile school units on playgrounds and parking lots as a “permanent solution” to overcrowding in black schools.

Lessons from the Heartland: A Turbulent Half-Century of Public Education in an Iconic American City. By Barbara Miner. (New Press, 2013). The history of Milwaukee, including the Civil Rights Movement struggles over education, housing, police brutality, and employment.

Q11: What other Civil Rights Movement events of note occurred in 1963?

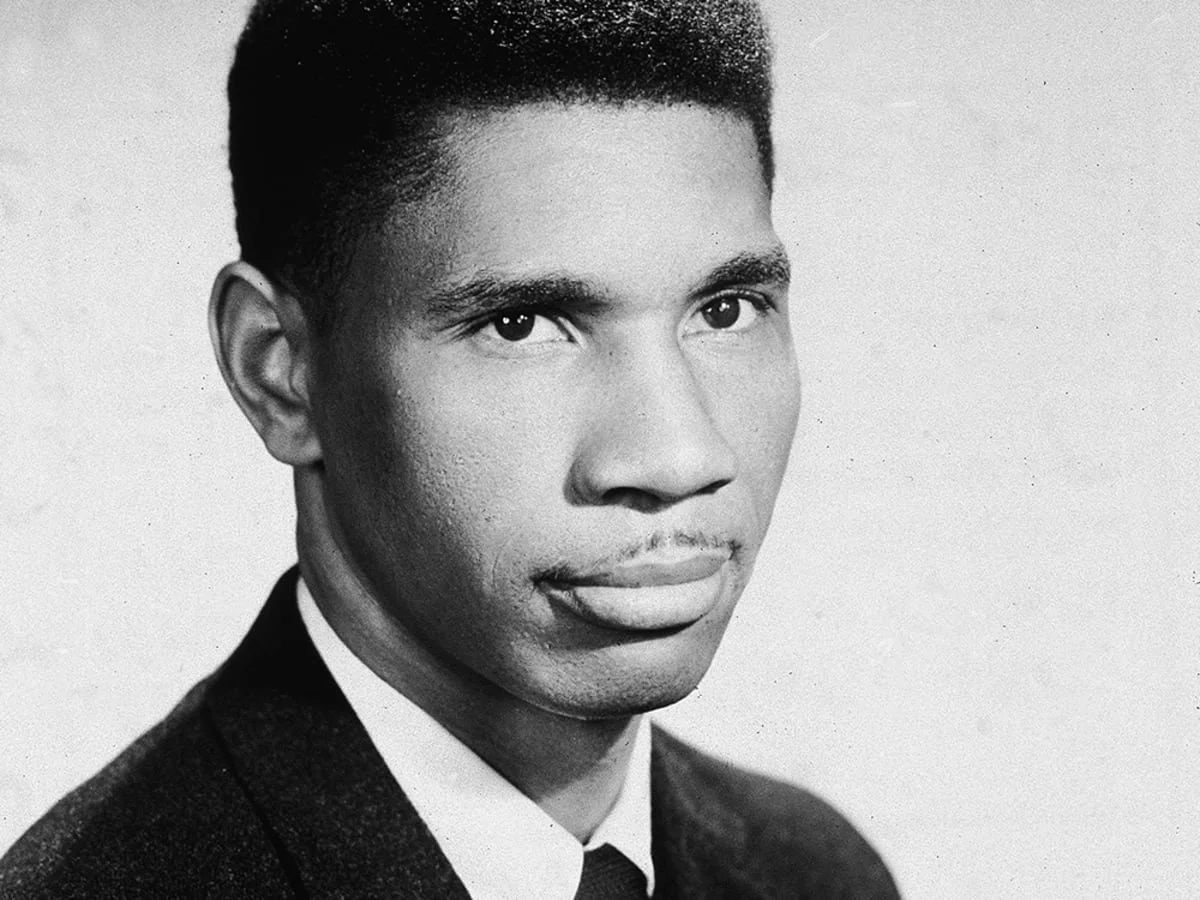

Medgar Evers

A: All of the above.

Textbook mentions of the modern Civil Rights Movement highlight 1963 as the year of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Occasionally, they will also reference the Children’s Crusade and the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., or the murder of Medgar Evers in Jackson, Miss., as isolated acts of resistance and racism.

Yet, it was a pivotal year as direct action, voter registration, and important strategic shifts occurred nationwide after several years of active and public struggle. Writer James Baldwin referred to the events, 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, as the “latest slave rebellion.”

A deeper understanding of these events and their interconnectedness (domestically and internationally) helps students “read” history and their contemporary world with a keener eye toward coordinated action.

If you like this quiz, make a donation to Teaching for Change so that we can continue to develop and share resources on the Civil Rights Movement. Contact Teaching for Change with corrections and/or additions.

© Teaching for Change