Montgomery Bus Boycott Mythbuster Quiz

Students from preschool through high school are often taught the simplistic narrative that Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat in Montgomery, the buses were desegregated, and the Civil Rights Movement was launched. Missing from that story are the strategic brilliance and courage of the African American community during the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the more complex history that led up to it. This quiz helps surface and challenge many of the myths about the boycott.

Questions and Answers

Below are the questions and answers to our Montgomery Bus Boycott Mythbuster Quiz.

Q1: African Americans fought against discrimination on public transportation in which century?

Ida B. Wells

A: All of the above. African Americans waged battles against discrimination on public transportation in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.

Seventy-one years before Rosa Parks defied the law on the bus in Montgomery, Alabama, anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells took a stand against segregated transportation.

On May 4, 1884, Wells was ordered to move to a segregated car on a train. Here is how she responded,

I refused, saying that the forward car [closest to the locomotive] was a smoker, and as I was in the ladies’ car, I proposed to stay. . . [The conductor] tried to drag me out of the seat, but the moment he caught hold of my arm I fastened my teeth in the back of his hand. I had braced my feet against the seat in front and was holding to the back, and as he had already been badly bitten he didn’t try it again by himself. He went forward and got the baggageman and another man to help him and of course they succeeded in dragging me out.

Wells ultimately sued the railroad company.

Elizabeth “Lizzie” Jennings

On July 16, 1854, school teacher Elizabeth “Lizzie” Jennings protested segregated streetcars in New York.

Frederick Douglass was another vocal opponent of the segregated system. In 1841 Douglass and his friend James N. Buffum entered a train car reserved for white passengers in Lynn, MA. When the conductor ordered them to leave the car, they refused. Douglass’ and Buffum’s actions led to similar incidents on the Eastern Railroad.

In 1870-1871, African Americans in Louisville, Kentucky organized a successful boycott of Jim Crow streetcars.

Widespread organizing led Congress to grant equal rights to Black citizens in public accommodations with the Civil Rights Act of 1875. However, the Supreme Court overturned this victory in 1883, declaring it unconstitutional.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century and in the early twentieth century, African Americans had boycotted streetcar lines in twenty-seven cities. There was a boycott of Montgomery’s Jim Crow car lines from 1900-1902.

On July 6, 1944 Lieutenant Jackie Robinson (of baseball fame), while stationed at Camp Hood near Waco, Texas, was instructed to move to a seat farther back. He refused and was court-martialed.

In 1953, African Americans in Louisiana organized the Baton Rouge Bus Boycott.

Learn More

Professor Barkley Brown produced a powerpoint on the history of resistance by women to discrimination on public transportation. Professor Blair Kelley documents early streetcar boycotts in Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship in the Era of Plessy v. Ferguson. Also, see this list of transportation protests from 1841-1992.

Q2: Prior to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, buses were evenly divided in half — the front for whites and the rear for Blacks.

A: False.

There was no endpoint for white passengers. The start of the “colored” section was determined by the number of whites on board. The more whites that boarded, the further back the white section extended. The more crowded the bus became with white patrons, the further the bus driver extended the white section in accommodation, regardless of the injustice to African American riders.

In addition to segregated and often non-existent seating, Black passengers suffered other abuses. For example, often they were required to pay in the front and then get off the bus to enter from the rear. During that time, the bus might just take off and leave them. In Household Workers Unite: The Untold Story of African American Women Who Built a Movement, author Premilla Nadasen describes the experience of domestic worker and activist Georgia Gilmore,

In October 1955, Georgia Gilmore had another in a long series of unpleasant encounters with city bus drivers, which prompted her to begin her own one-woman boycott. During Friday afternoon rush hour, Gilmore boarded a packed Oak Park bus. There were two white passengers; the rest were African Americans. Although she didn’t know the driver’s name, she recognized him. “This bus driver is tall, hair red, and has freckles, and wears glasses. He is a very nasty bus driver.” After she paid her fare, the driver told her to get off the bus and enter through the rear door. She pleaded with him to let her stand there, since she was already on the bus and most of the riders were African Americans in any case. The driver refused. “So, I got off the front door and went around the side of the bus to get in the back door, and when I reached the back door and was about to get on he shut the back door and pulled off, and I didn’t even ride the bus after paying my fare.

Learn more about the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

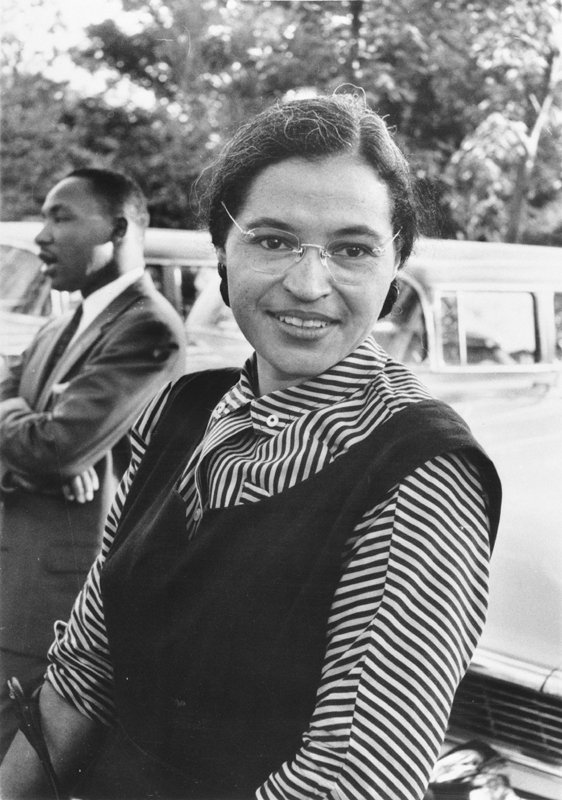

Q3: Which of the following is true of Rosa Parks, the woman who sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955 when she was arrested for defying the law segregating the city’s buses?

A: As secretary of the local NAACP chapter and leader of its Youth Group, Rosa Parks had a long history of activism.

At the time of the bus boycott, the 43-year-old Mrs. Rosa Parks had already had several run-ins with bus drivers because she refused to pay her money at the front of the bus and go to the back to get on. In fact, the bus driver who called the police on December 1, 1955 had previously thrown Parks off the bus in 1943 because she refused to enter by the back door.

Parks had been active in the southern freedom movement since the 1940s. She had been secretary of the local NAACP since 1943. In Montgomery, where 37% of the population was Black, but only 3.7% were registered voters, Parks tried numerous times to register to vote between 1943-1945. After multiple attempts, taking notes on the literacy test which she intended to use to sue, and paying a significant poll tax, she succeeded in voting in the 1945 election.

Parks was active and committed to exposing the mistreatment of African Americans under the law, seeking justice for African American victims of white violence, exposing the murders of African Americans by whites, investigating rapes of African American women by white men, and reporting on instances of voter intimidation. Jeanne Theoharris describes Parks’ work in this era in The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks:

Traveling throughout the state, Rosa Parks sought to document instances of white-on-Black brutality in hopes of pursuing legal justice. “Rosa will talk to you,” became the understanding throughout Alabama’s Black communities.

In 1955, after Brown v. Board of Education ended legal segregation in schools, Parks was active in local efforts to desegregate them.

Parks attended leadership conferences run by Ella Baker in 1945 and 1946, where she was trained to develop ways to attack community problems and to see them as part of larger systemic issues. In the summer of 1955 she won a scholarship to attend a two week, interracial workshop at Tennessee’s Highlander Folk Center, an important adult education facility deeply involved in the Civil Rights Movement. (Highlander was co-founded by Myles Horton.)

During the training she wrote in her notes, “Desegregation proves itself by being put into action. Not changing attitudes, attitudes will change.” Five months later, Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus.

Q4: After Rosa Parks was arrested, the Montgomery Bus Boycott was first set in motion when:

A: The Women’s Political Council, with Jo Ann Robinson as president, distributed thousands of leaflets urging Black residents of Montgomery to boycott public transportation.

The crucial role of women, grassroots organizers, and rank-and-file citizens in the civil rights movement is often overlooked. Under the leadership of Ms. Jo Ann Robinson, a college English professor, Montgomery’s Women’s Political Council began organizing against segregated buses in 1949. In March 1954, Robinson wrote a letter to the mayor of Montgomery, Alabama.

More and more of our people are already arranging with neighbors and friends to ride to keep from being insulted and humiliated by bus drivers. There has been talk from twenty-five or more local organizations of planning a city-wide boycott of buses. We, sir, do not feel that forceful measures are necessary in bargaining for a convenience which is right for all bus passengers.

The Women’s Political Council built a city-wide network of over 300 supporters that made it possible to organize the Black citizens quickly after Rosa Parks was arrested. Said Robinson:

The Women’s Political Council had begun in 1946, after just dozens of Black people had been arrested on the buses for segregation purposes. By 1955, we had members in every elementary, junior high, and senior high school, and in federal, state, and local jobs. Wherever there were more than ten Blacks employed, we had a member there. We were prepared to the point that we knew in a matter of hours, we could corral the whole city.

NAACP leader and labor organizer E.D. Nixon bailed Parks out of jail and convened a meeting of ministers at the end of the first day of the boycott to provide leadership. At that meeting, the ministers formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) and elected the 27-year-old Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. as its leader. King’s oratory and leadership helped sustain the movement, but its victory was built on the daily contributions of many unsung activists. Key to the success of the boycott was the activism of domestic workers in Montgomery.

Q5: How long did it take Black residents of Montgomery to begin mobilizing for the Montgomery Bus Boycott?

A: One day.

The night of Rosa Parks’ arrest, Jo Ann Robinson, president of the Women’s Political Council, put plans for a one-day boycott into action. Using the college mimeograph machine at night, she copied thirty-five thousand handouts urging Blacks to stay off the city buses on Monday, when Parks’ case was due to come up. The next day, Friday morning between classes, Robinson and two of her students distributed the anonymous fliers throughout Montgomery. Support for the boycott was further intensified that weekend by Sunday church sermons and the local Black-owned paper, the Montgomery Advertiser.

While it took only one day to begin mobilization, the boycott itself lasted 381 days, to be exact. During this time, 50,000 citizens had to sacrifice every day to sustain the boycott and change the course of history.

African Americans traveled through “private taxi” systems, carpooled, and thousands walked to work. The movement depended on the many people who organized fundraising activities, car pools, and coordinated taxi service.

Some churches purchased station wagons, usually called “rolling churches,” to be used in the private taxi service. There were 325 private taxis, 43 dispatch stations, and 42 pickup sites. Rufus Lewis, who was chairman of the transportation committee, explained:

Those folks who had cars would register them in the pool, and register the time that they would be usable, and from that we could serve the people… We had a transportation center downtown, a parking lot… People would call in, say, “I’m out here on Cloverdale Road in such-and-such a block, and I’ll be ready at such-and-such a time.”… When we bring them to the center, then all of those people who lived in North Montgomery would get into a car and be carried to their place in North Montgomery.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. recalled that on the first day of the boycott:

While some rode in cabs or private cars, others used less conventional means. Men were seen riding mules to work, and more than one horse-drawn buggy drove the streets of Montgomery that day.

Learn more about the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Q6: Which of the following individuals publicly took stands against segregated busing in Montgomery prior to the Montgomery Bus Boycott?

Claudette Colvin

A: All of the above

Many people whose names’ are not readily known or celebrated, protested segregated buses. In 1949, Jo Ann Robinson absentmindedly sat at the front of a nearly empty bus. The bus driver screamed at her and ran her off the bus. In the early 1950s, Vernon Johns tried to get other Blacks to leave a bus in protest after he was forced to give up his seat to a white man. On October 15, 1955, eighteen year old Mary Louise Smith refused an order to relinquish her seat. She was arrested and charged with failure to obey segregation orders and given a nine dollar fine.

In early 1955, fifteen year old high school student Claudette Colvin was arrested for refusing to give up her seat. In a 2013 interview she explained:

They asked me to get up, and I refused… two squad car policemen came on the bus. And I became more defiant. And when they asked me the same question, and the gal, “Why are you sitting there?” I said, “It’s my constitutional right. I paid my fare; it’s my constitutional right.” And he said, “Constitutional rights?” And then one kicked at me, and he knocked the books out of my hand, out of my lap. And then one grabbed one arm, and one grabbed the other, and they manhandled me off the bus. And after I got into the squad car, they handcuffed me through the window and took me to booking and then to–not to a juvenile facility–but to an adult jail. And I stayed in jail three—approximately three hours, until my pastor, Reverend H.H. Johnson, and my mother came and bailed me out.

Q7: Which of the following methods were used to undermine the Montgomery Bus Boycott?

Home of Dr. Martin Luther King after it was firebombed.

A: All of the above.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott was guided by the credo of nonviolent resistance, even in the face of a police crackdown and attempts by white supremacists to undermine the protest.

Montgomery police threatened to arrest taxi drivers giving discount rates to the Black riders, and when the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) arranged carpools, the police systematically harassed drivers, giving them traffic tickets and arresting them for allegedly going too fast or too slow.

Meanwhile, the boycott leaders squared off at the bargaining table with the local officials. The MIA presented its modest demands for bus seating by race, with no mobile area, and “Negro routes” with Black drivers. They were met with unconditional refusal. The MIA was hopeful that the plan would be accepted and the boycott would end, but the bus company refused to consider it. In addition, city officials struck a blow to the boycott when they announced that any cab driver charging less than the 45-cent minimum fare would be prosecuted. Since the boycott began, the Black cab services had been charging Blacks only 10 cents to ride, the same as the bus fare, but this service would be no more.

Under a 1921 ordinance, 156 protesters were arrested for “hindering” a bus, including Martin Luther King Jr. He was ordered to pay a $1,000 fine or serve 386 days in jail. The move backfired by bringing national attention to the protest.

Learn more about the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Q8: White owned newspapers published false information to try to stop the boycott.

A: True

Whites tried to end the boycott in every way possible. One often-used method was to try to divide the Black community.

On January 21, 1956, the City Commission met with three Black ministers who were not part of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) and proposed a “compromise,” which was basically the system already in effect. The ministers accepted, and the commission leaked false reports to a newspaper that the boycott was over.

The MIA did not even hear of the compromise until a Black reporter in the North who received a wire report phoned to ask if the Montgomery Blacks had really settled for so little. By that time it was Saturday night. On Sunday morning Montgomery newspapers were going to print the news that the boycott was over. To prevent the boycott being derailed by misinformation, some MIA officials went from bar to bar to spread the word that the stories were a hoax and that the boycott was still on.

Learn more about the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Q9: The Montgomery Bus Boycott received financial and political support from:

A: All of the above.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott was supported both nationally and internationally. Churches nationwide raised funds and even sent shoes to Montgomery to aid and support residents in their protest.

One group that organized to provide support was called “In Friendship.” As is explained on the King Encyclopedia at Stanford, “On January 5, 1956, one month after the start of the Montgomery bus boycott, New York–based In Friendship was formed to direct economic aid to the South’s growing civil rights struggle. Founded by Ella Baker, Stanley Levison, Bayard Rustin, and representatives from more than 25 religious, political, and labor groups, In Friendship sought to assist grassroots activists who were, ‘‘suffering economic reprisals because of their fight against segregation.” During its three years of operation, the organization contributed thousands of dollars to support the work of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA).” Read more.

The protest also inspired protests for desegregation in other countries such as the Bristol Bus Boycott in England.

Learn more about the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Q10: The Montgomery Bus Boycott lasted over one year. One reason is that committees supporting the boycott were very well organized. Another reason the boycott lasted so long is:

A: Even after the bus company was ready to desegregate in April 1956, the local police and judges forced the bus company to continue to resist the boycotters’ demands.

The bus company as well as the Montgomery business community took a huge financial loss due to the boycott. Downtown businesses were becoming frustrated with the boycott, which was costing them thousands of dollars because Blacks were less likely to shop in stores. Although they were opposed to integration, store owners realized that the boycott was bad for business and therefore wanted it to end.

Financially hurt by the boycott, Montgomery’s bus company planned to desegregate in April of 1956 in an attempt to minimize further debt, but was forced by local police and judges to continue segregating.

In the end the 381-day boycott, combined with a legal case, led to the desegregation of the buses. The legal case was Browder v. Gayle, 352 U.S. 903 (1956). It was filed by Fred Gray and others on the behalf of four women (including Claudette Colvin) who had been mistreated on city buses. The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court which upheld a district court ruling that a state statute requiring segregation on buses was unconstitutional.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott provides powerful lessons for challenging injustice today about the combined use of grassroots organizing, legal strategies, the media, and more.

Learn more about the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

If you like this quiz, make a donation to Teaching for Change so that we can continue to develop and share resources on the Civil Rights Movement. Contact Teaching for Change with corrections and/or additions.

© Teaching for Change