Teaching the 1964 New York City School Boycott

Teaching Reflection by Adam Sanchez

For the complete lesson and classroom materials that accompany this article, go to Rethinking Schools.

“Selma!”

“Birmingham!”

“Washington, D.C.!”

Struggling to remember their Southern geography, my students slowly rattled off cities that came to mind. I had asked them, “Where did the largest civil rights protest of the 1960s take place?” Their answers, building off of the traditional civil rights narrative they had learned in elementary and middle school, mostly consisted of Southern cities. They were wrong. The real answer is New York City, where most of my students were born and raised.

This, of course, was no shock to me. Despite obligatory coverage of the Civil Rights Movement in every history textbook, I have yet to find a single K–12 textbook that mentions the boycott against segregated schools in which 464,361 students — about 45 percent of all NYC students at the time — stayed home from school. This demonstration was nearly twice as big as the March on Washington but is ignored in textbooks and most popular accounts of the movement.

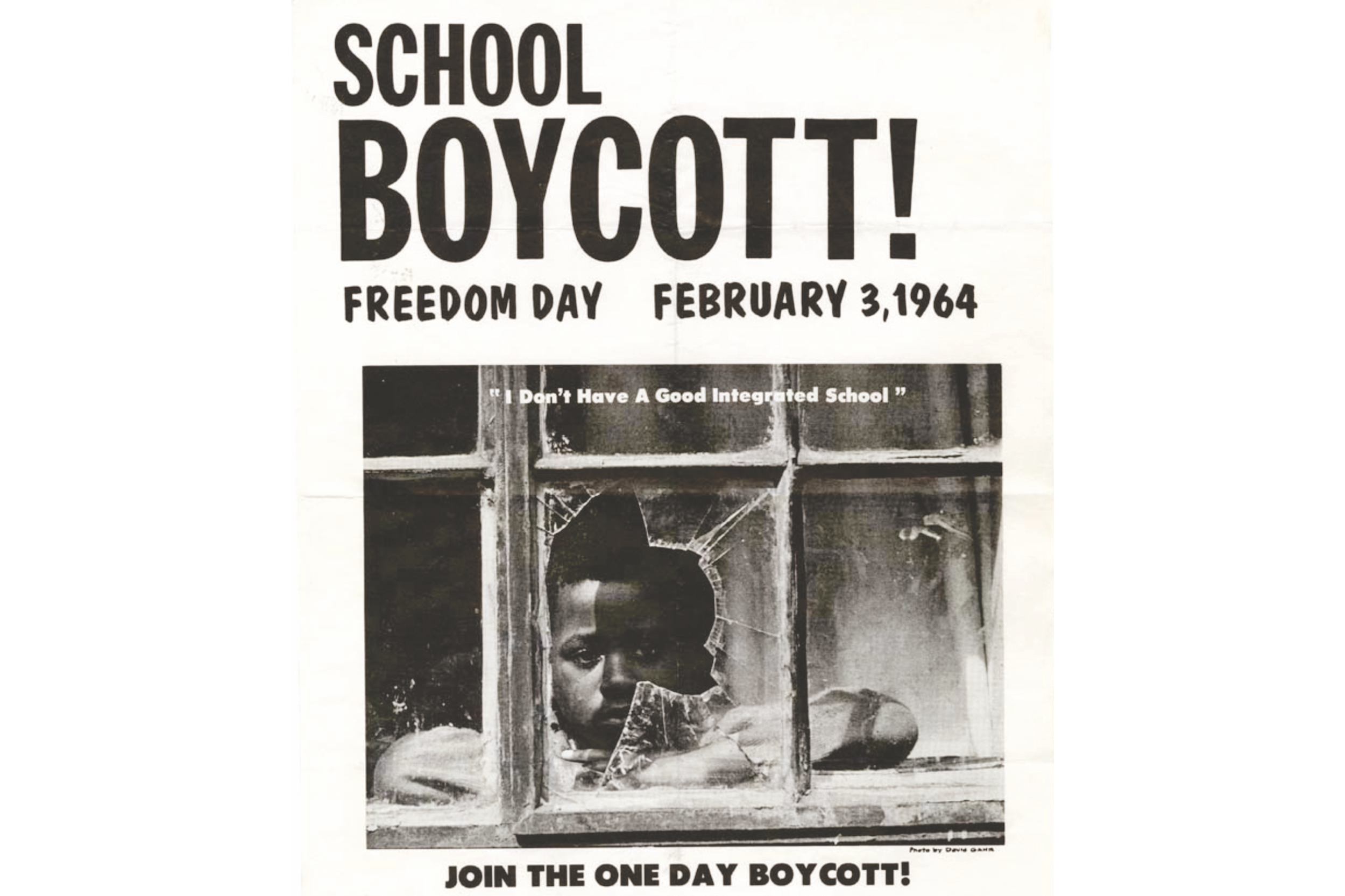

City Wide Committee for Integrated Schools School Boycott flier calling for a one day school boycott in New York City on February 3, 1964, to protest school segregation. More than 450,000 students refused to attend their respective schools on the day of the boycott. Source: Elliot Linzer Collection, Queens College Civil Rights Archive

The traditional narrative of the Civil Rights Movement tells a story of a movement that exclusively fought against racist laws in the South. This narrative reinforces the myth of progress, one in which most Americans, especially those in the North, responded positively to the demands of the Civil Rights Movement and righted the wrongs of lingering Southern racism. The movement, in this story, ends victorious when the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 strike down Jim Crow laws in the South. While these laws were momentous victories, they encompassed only a small fraction of the movement’s goals. Painting them as the fulfillment of the struggle against racism is a fable that ignores more than it reveals.

Indeed, when I was in school, I had also been taught the Civil Rights Movement as an exclusively Southern struggle, and so had been teaching it as such. I made efforts to complicate the traditional narrative — focusing on organizations like SNCC and complicating simplistic portrayals of national figures like Martin Luther King Jr. — but for the most part the story my New York City students learned was a Southern one. This led to a disconnect my student Morganne expressed succinctly: “Before I knew that people in New York City were a part of the Civil Rights Movement I couldn’t see myself in the movement. It felt like everything happened in the South — and the West and the North were just sitting back and watching everything.”

The more I read about the Northern movement, from Thomas Sugrue’s Sweet Land of Liberty to Jeanne Theoharis’ A More Beautiful and Terrible History, the more I realized I needed to change my teaching to more accurately reflect the national Black freedom struggle and help students draw out its pertinence. The real Civil Rights Movement was not just about tearing down legal barriers, but about economic inequality, criminal injustice, police brutality, and access to quality education and healthcare. This movement was national in scope, led by young people, and confronted segregation and racism in both the North and the South.

Between 1940 and 1960, 2.5 million Black people and nearly 1 million Puerto Ricans migrated to New York City and found that most landlords refused to rent to people of color. The government maintained residential segregation in New York through a process commonly referred to as redlining. Neighborhoods were given an A to D rating. Ones with more than 5 percent people of color were given C and D ratings. This meant that homeowners or storeowners in Black or racially mixed neighborhoods could not get loans to update their property, leading to deteriorating conditions. At the same time, it encouraged white landlords and homeowners to keep out people of color for fear that their neighborhood might get a lower grade and deteriorate as well.

Flier calling for a one day school boycott on March 16, 1964, in New York City to protest school segregation. Elliot Linzer Collection, Queens College Civil Rights Archive

These government policies led to overcrowding in the Black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods and schools. Instead of redrawing the school boundaries to send students to less crowded white schools, the school board implemented part-time school days. When the board — under pressure from civil rights activists in the wake of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision — finally attempted to bus some students to alleviate overcrowding, they faced fierce resistance from white parents. In 1958, when nine mothers in Harlem decided to keep their kids out of school to “demand a fair share of the pie,” the city decided to bring them up on charges for failure to send their children to school. By 1964, frustrations with the poor education Black and Puerto Rican students were receiving in New York led civil rights leaders to call for a one-day boycott of all schools. In the 10 years between the Brown decision and the boycott, segregation in New York City schools had quadrupled.