Advanced Ideas About Democracy

Reading by Vincent Harding

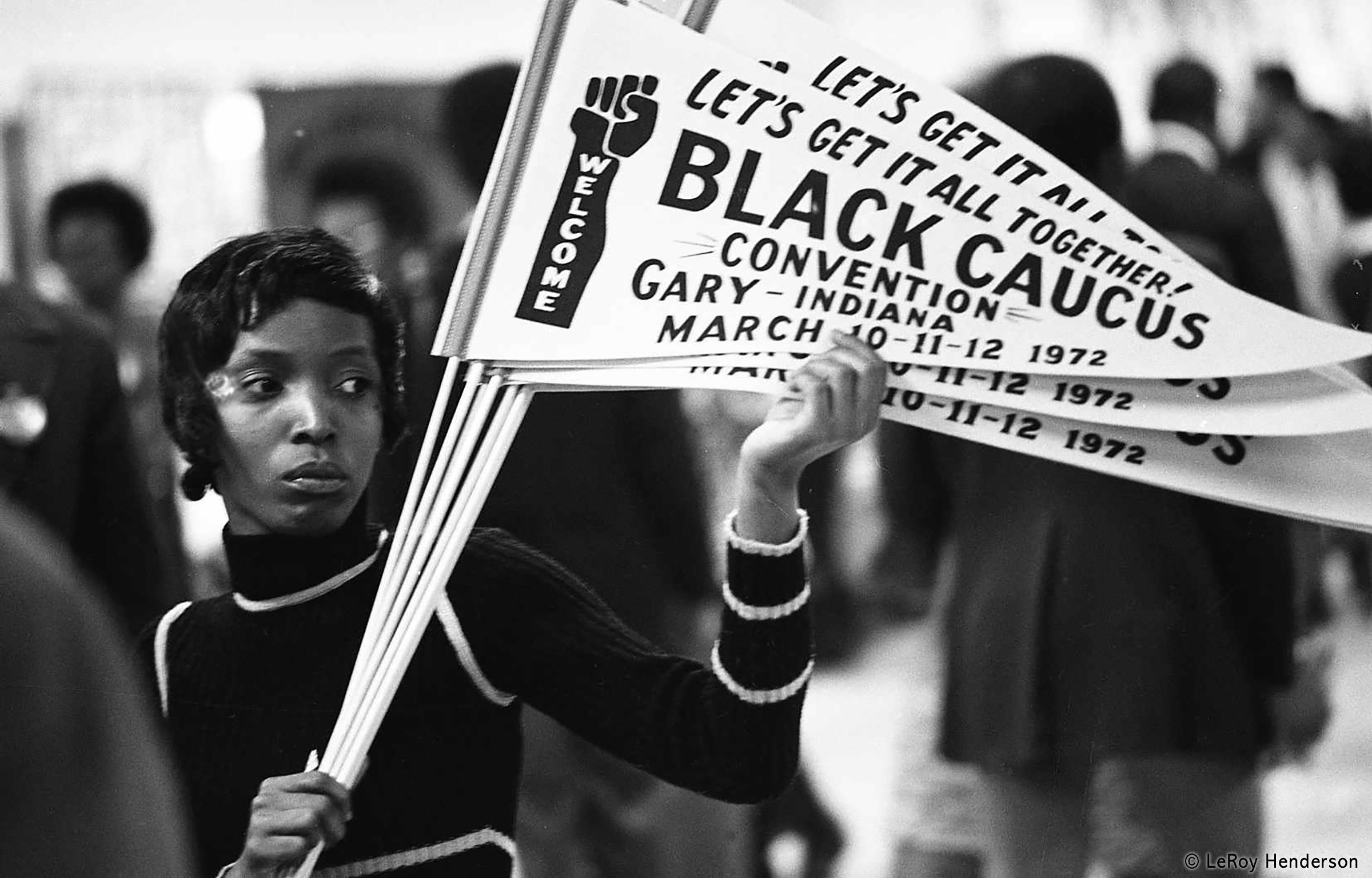

A woman holds pennants at the National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana in 1972. By LeRoy Henderson.

Theologian, historian, and nonviolent activist Vincent Harding (1931–2014) provides an annotated list of historic events for teaching the full story of the Civil Rights Movement.

Concrete historical examples from the post-World War II freedom movement are endless, but a number of them, outlined below, suffice to suggest the richness of the stories available for teaching about the struggle for democracy.

These excerpts were selected by the editors from Harding’s essay in Hope and History: Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement. They highlight stories that are not addressed in-depth elsewhere in Putting the Movement Back Into Civil Rights Teaching.

The Sit-ins and Freedom Rides

King’s 1966 Chicago Campaign

The Poor People’s Campaign

The Struggle for Black Studies and Black Education

Attica

The Gary Convention

The Sit-Ins and Freedom Rides

Reflection on these signal events of the early 1960s can only deepen our continuing sense of wonder at and appreciation for the powerful role played by young people in the mounting of awesome challenges to Southern antidemocratic practices, in the calling of the entire nation to its best self. What strikes us no less sharply is the fact that the distance from the sit-ins and freedom rides to Tiananmen Square is far shorter than we may imagine. For in both situations we are drawn by the great courage and moral authority of costly, nonviolent civil disobedience led by young people who are willing to die for the advancement of democracy in their society.

Facing these audacious actions, focusing on the sit-ins and freedom rides, it is impossible to escape certain central, continuing themes and questions crucial to the study and practice of expanding democracy: the role of youth; the power of sacrificial, often joyful, nonviolent direct action; the inevitability of frequently violent resistance from those who seek to maintain the status quo. And of course, there was always the important question: How shall nonviolent democratic activists respond to violent acts of repression? (During much of the sit-in and freedom-ride action, there was a conscious decision to respond to violence by regrouping and advancing even more deeply into the contested territory, refusing to allow the momentum to pass into the hands of the attackers.)

Finally, one of the most important issues brought to the fore by the study of the sit-ins and freedom rides was the capacity of such movements — largely by virtue of their audacity and sense of moral authority — to attract participating allies from the white majority and thereby offer them a new purpose in life.

King’s 1966 Chicago Campaign

This is an important counterpoint to the Mississippi story, for it provides significant lessons concerning some of the differences and similarities, between organizing for justice and democracy from Southern, rural-based settings, and carrying on such organizing work in the quintessential bastion of Northern, urban, de facto segregation. (How Chicago came to be such an archetype of American racism, and at the same time developed some of the nation’s most powerful Black urban cultural gifts, is another fascinating and paradoxical story for our students to explore.)

The immediate failure of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s (SCLC) relatively whirlwind kind of organizing approach, compared to the years of digging in, planting, nurturing, and harvesting that went on in Mississippi [by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party], is most instructive, especially for those of us who seek to work for justice and democratic development in such Northern settings.

Many important questions are raised here concerning the goals, methodologies, and focal points for pro-democracy work in the deteriorating cities, in the cities where poorer Black folks and their middle-class kindred are living farther and farther apart. (Some of these issues are best seen, of course, from a perspective like the story of the election of Harold Washington as the first Black mayor of Chicago, some 17 years after King’s 1966 campaign.) Here, too, as we consider the power of the forces of Mayor Richard Daley, it is possible to introduce and reflect on the role of urban political machines and their African American constituents. What has been their function as proponents of, or hindrances to, the flowering of serious democratic development?

At the same time, the King-Chicago story cannot be approached without our cultivating a sense of the great, explosive, urban pressures that were building in the United States by the time King’s organization arrived in that city, thus providing a very different and far more volatile setting for community organizing than had been known before. Indeed, one of the most important questions that arises out of the Chicago experience is the part played by the urban uprisings in the expansion of American democracy. How many doors to democratic participation were opened because of the fires on their threshold? What happens to such doors and the participatory access when the fires are banked — or when they begin to burn inwardly, out of control, consuming vital parts of many young lives?

The Poor People’s Campaign

For most students of all ages, the Poor People’s Campaign is at best a source of vague memories. However, as we explore the story of the struggle for the expansion of democracy in America, it is important to grasp the original vision of the campaign. It raises with us crucial issues, especially concerning the relationship between political and economic democracy. Do the limits set by our society on economic opportunities for all really limit the possibilities and narrow the range of democratic political participation as well?

Another obvious issue has to do with methodology and strategy in the struggle for democracy. We may wish to ask, for instance, how much of the kind of organizing that led to breakthroughs in political democracy might be utilized in working for greater economic opportunities for all Americans? As an example, toward the end of his life King was explicitly moving to test the possibilities of using nonviolent direct action, particularly “massive civil disobedience” in the nation’s capital, as a means of confronting our political leadership (and the nation at large, through the media) with the serious and profoundly systemic problems faced by the poor.

The use of nonviolent direct action on behalf of a more just (and therefore more democratic) economic order is still a relatively unexplored area among us. But as the interracial gap between rich and poor, between relatively comfortable and very uncomfortable, continues to widen (and as thousands of young people and others attempt to fill the gap from the bloodied cornucopia of drug-based cash), King’s vision of audacious, nonviolent revolutionary challenges to the status quo is more than a quaint religious oddity. How shall we deal with it?

Finally, one of the hallmarks of King’s Poor People’s Campaign plan was not only its radical nonviolence but its bold attempt to mobilize poor people and their allies across racial lines, especially targeting poor whites, Latinos, and Native Americans to combine with his African American base community. Can the struggle for economic justice in America be envisioned without such a coalition? In other words, can the poor, especially people of color, again become powerful subjects rather than mere objects of social change? Might our students have any thoughts, any role, here?

The Struggle for Black Studies and Black Education

Although we do not often place this powerful educational, cultural, and political thrust into the context of the quest for the expansion of democracy, it certainly belongs there. For the partially successful, continuing movement for a Black-orbed re-visioning of American education was actually one of the “advanced ideas” of democracy that emerged out of the freedom and justice movement, out of the creative quest for self-determination and Black consciousness. Indeed, it will be important for our students to realize that this particular educational struggle did not come from the initiatives of formal educational institutions, was not a reflection of a benign liberal enlightenment on the part of our “best” white mainstream colleges and universities.

Rather, the initial calls for a more authentic Black educational and cultural vision (a more faithful American vision) came from hundreds of local Black communities, from highly charged forums, conferences, debates, and discussions on the educational implications of Black power and Black consciousness, on the responsibilities of a people to define their own past as well as their present and future. In many ways, it was part of an urgent thrust to develop a more democratic understanding of the truth of America itself.

For there was much more here than a demand for additional Black professors, students, or pages in textbooks. All of these were part of a larger, democratic movement to break an unjust and unenlightened white male cultural, intellectual, and political hegemony. The essential questions being addressed in the late 1960s and early 1970s were: Who shall participate in the crucial process of defining the good, the true, and the beautiful in our society? Who shall determine what (and who) is worthy of being studied, especially by our children? As we have seen, the answers to those questions are filled with explosive psychological, cultural, and political implications.

In that context, the struggle for Black Studies — which paved the way for an expanding multicultural educational vision of America — was an attempt to open the arena, to say that there is more to American history than white-defined history, more to American literature than white-established canons, more to “the American people” than a collection of blond and blue-eyed Norman Rockwell creations.

Students at every level surely need to reflect on how educational systems and assumptions are formed, to recognize the hidden politics of education, to ask how education itself can contribute to a more democratic society. So it will be helpful for them to recognize in this movement a firm determination by many kinds of Black people (and a significant minority of white allies) that the democratic, Black-and-white truth of America be acknowledged, be researched, be published, and be taught at every level of our nation’s life. In other words, it was (and still is) the quest for an American education true to the best visions and values, true to the subjective and objective realities of its people.

More Black books, stories, poems, students, and faculty were only necessary means to the larger goal of a truthful democratic singing and seeing of the nation. So let our students hear Paul Robeson sing “The House I Live In,” beginning with the words, “What is America to me? A word, a map, a flag I see/ A certain word, democracy.” He may help them, and us, to understand. For his words and his life surely carried “advanced ideas” about democracy, and he paid the price for them. Let us hear him.

It may be, then, that if our students understand these things, they will also see and hear more clearly the meaning of educational and political struggles like the one that the second part of the Eyes on the Prize series documents from the Ocean Hill-Brownsville section of Brooklyn. For in this and similar settings across the nation, Black parents sought to take greater democratic responsibility for the education of their children. They did it partly in order to break the hegemony of insensitive, often destructive, white-defined and -controlled education in their schools. They did it as well in order to test the possibilities of democracy and the great, untapped potentials of their children.

In a sense, they were parenting both their natural offspring and the possibilities of their nation. Because we are still young in our life as an officially democratic, multiracial society, this struggle for a democratic content and organization for the educational process must continue for a long time.

We will probably be amazed by the capacities of our students to see the meaning and participate in the continuation of this movement, and it will likely be our task to face with courage all the untidy, disorderly implications of truly democratic educational experimentation. But how else can democracy be nurtured?

Attica

One of the most difficult and yet most imperative events to approach with our students is the story of the Attica prison uprising of September 1971, especially as it is conveyed to us in Eyes on the Prize II. There are, of course, many reasons for the difficulty: We are initially uncomfortable with the inner world of prisons, for we often put men and women there so that we will not have to face them, fear them, think of them anymore. In Attica, as in many other places, we are dealing with men who [may] have committed real crimes, sometimes terrible and ferocious crimes, and we are ill at ease in their presence. Besides, the Attica story — when it is vaguely remembered — seems to be one of great, unmitigated tragedy, and we do not see how it fits into our explorations of the expansion of democracy. We certainly wonder how young people, or church folk, or synagogue members — or prisoners — would respond to the often-chilling images and the no less chilling thoughts that the Eyes film promotes.

Nevertheless, serious teaching about American democracy demands serious attention to America’s penal system and all its antidemocratic elements. More specifically, any of us who are exploring the story of the African American freedom movement for its contributions to democratic expansion must confront the fact that there is a vast and wounded army of Black young men (and women as well, but the Attica focus is on the men) wasting their lives in prison, unavailable to any pro-democracy movement. But the Attica uprising — as well as the attention to Malcolm X earlier in the Eyes II series — suggests that there are other messages here. There is more to Attica than meets our first glance.

For instance, one of the most powerful themes at work in this story is that of men who are trying to remake their lives and their community under hostile fire, under the glare of television, and so very late in their lives. No matter how late they are, they testify to the continuation, even under the harshest circumstances, of that deep and hidden spark, that human desire to participate in re-creation.

On one crucial level, the Attica rebels were attempting to build, physically and spiritually, a new, more democratic society in the courtyard of the old — under the guns of the old. In the Eyes film, New York state legislator Arthur O. Eve, one of the observers who went into the besieged prison, remembered the spirit he found there. He said, “It was almost a community within a community. And it was very, very impressive that they had said, ‘This is our home and we’re now going to make it as livable as possible.’ And there was a tremendous amount of discipline there within the yard.”

That was true. After the first terrible and confused moments of the rebellion, there was no striking out by the men, no torturing, no beating up of hostages or anyone else. Rather, their major energies were being spent on building and maintaining the integrity of their new community in the prison yard, on testing the possibility of their new lives (isn’t that what the homemade dashikis meant?), on challenging the authorities to let them experiment with self-determination and self-reform, either in the United States or in overseas exile.

We ponder this not only because of Attica, but because Black young men currently make up nearly half of the nation’s prison population, and if transformation is not possible within those walls, what is our future, as a nation, as a people, as a democracy? These are crucial questions, and the testimony of the observers who went into Attica must be taken seriously. They said they found love, compassion, and a sense of integrity and responsibility among those “rejected stones” of our society. What are the implications of such testimony? Can these men and others like them really be cast aside if democracy is to be expanded and rebuilt in America? Somehow inmate Frank “Big Black” Smith, in all the sheer strength of his awesome storytelling presence, confronts us with these issues. When we guess at who he once was, when we hear his story of the transformative and terrible Attica experience, when we realize that he is now serving others as a worker in a social agency, we are faced with the issue of hope, the question of possibilities, the vision of transformation.

How shall the best gifts of wasted men and women be rescued and harnessed for the great work of building a democratic and healing society? In the context of such questions, if we face them, Attica may become a gift, a watering place for the trees of enlightenment in America.

Editor’s note: In addition to Eyes on the Prize II, find more resources for teaching about Attica at the Zinn Education Project.

The Gary Convention

One of the signal characteristics of the African American freedom movement has been its basic resiliency, its capacity to recover from harsh blows, to persevere against literally murderous pressures. The story of the National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana, in 1972 is another example of that vitality. This important gathering of African Americans took place amidst the repression and subversion, while the mourners’ songs continued to echo in our hearts. And yet Gary was still able to evoke and embody the persistent African American search for a creative tension between our calling as the prime keepers of the flame of American democracy and our responsibility to create and develop independent visions and institutions that nourish the Black community. If students can understand — indeed, feel and appreciate — that tension, they may learn the difference between racial solidarity and racial separatism.

Perhaps a study of Gary on film and in some of its documents will help us to recognize the vision of a new society that continued to emerge out of all the terrors of the old. For instance, it might be helpful to share with our students portions of a document that became the basis for many of the convention’s statements on the necessity of independent Black political organizing. For many people of that time saw such empowering Black organizing as a prerequisite not only for Black life here, but for the advancement of democracy and the transformation of the American nation as a whole. Here are excerpts from the Gary Declaration, the call to the convention:

Let there be no mistake. We come to Gary in a time of unrelieved crisis for our people. From every rural community in Alabama to the high-rise compounds of Chicago, we bring to this Convention the agonies of the masses of our people. From the sprawling Black cities of Watts and Nairobi in the West to the decay of Harlem and Roxbury in the East, the testimony we bear is the same. We are witnesses to social disaster.

Our cities are crime-haunted dying grounds. Huge sectors of our youth — and countless others — face permanent unemployment. Those of us who work find our paychecks able to purchase less and less. Neither the courts nor the prisons contribute to anything resembling justice or reformation. The schools are unable — or unwilling — to educate our children for the real world of our struggles. Meanwhile, the officially approved epidemic of drugs threatens to wipe out the minds and strength of our best young warriors.

. . . So, let it be clear to us now: The desperation of our people, the agonies of our cities, the desolation of our countryside, the pollution of the air and the water — these things will not be significantly affected by new faces in the old places in Washington, D.C. This is the truth we must face here in Gary if we are to join our people everywhere in the movement forward toward liberation.

A Black political convention, indeed, all truly Black politics, must begin from this truth: The American system does not work for the masses of our people, and it cannot be made to work without radical, fundamental change. (Indeed, this system does not really work in favor of the humanity of anyone in America.)

. . . So we come to Gary confronted with a choice. But it is not the old convention question of which candidate shall we support, the pointless question of who is to preside over a decaying and unsalvageable system. No, if we come to Gary out of the realities of the Black communities of this land, then the only real choice for us is whether or not we will live by the truth we know, whether we will move to organize independently, move to struggle for fundamental transformation, for the creation of new directions, towards a concern for the life and the meaning of Man. Social transformation or social destruction, those are our only real choices.

. . . The challenge is thrown to us here in Gary. It is the challenge to consolidate and organize our own Black role as the vanguard in the struggle for a new society. To accept that challenge is to move to independent Black politics. There can be no equivocation on that issue. History leaves us no other choice. White politics has not and cannot bring the changes we need.

. . . So, brothers and sisters of our developing Black nation, we now stand at Gary as a people whose time has come. From every corner of Black America, from all liberation movements of the Third World, from the graves of our fathers and the coming world of our children, we are faced with a challenge and a call: Though the moment is perilous, we must not despair. We must seize the time, for the time is ours.

We begin here and now in Gary. We begin with an independent Black political movement, an independent Black political Agenda, an independent Black spirit. Nothing less will do. We must build for our people. We must build for our world. We stand on the edge of history. We cannot turn back.

If we can help our students grasp the vision and the passion represented in these words, then they may see the great tension that continues to mark the African American struggle for democracy and integrity. In the context of our own present moment, it will probably be illuminating to help students obtain documents of the 1989 National Black Political Convention, held in New Orleans this time. What will comparisons reveal? What would our students write today if they were asked to compose a similar document faithful to our time and their vision?

Perhaps at some point in this discussion we will find the courage and the right spirit to ask another version of a necessary but very painful question: In light of the central, exemplary role played by African Americans in the historic struggle for the expansion of democracy in this land, what do the depredations of joblessness, poverty, drugs, class gaps, and the weakening of older institutions of support mean for the future of Black people, for the future of democracy in America? Are we still, with the Gary Convention, “at the edge of history,” still fervent seekers of the “advanced ideas”? And when we set ourselves in the [current] context, are African Americans the only people who need to face and address such questions? ■

© 1990 Blackside Inc. Reprinted with permission from Vincent Harding, Hope and History: Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement (Orbis Books, 1990).

Intellectual McCarthyism

Scholar Charisse Burden-Stelly suggests there are more stories that are missing from the traditional curriculum on the Civil Rights Movement, obscured by what she refers to as intellectual McCarthyism. In an interview in April 2021 on The Dig podcast, she explains:

So because racial liberalism is by and large consonant with the pedagogy of the state, we know much more about, for example, a Thurgood Marshall than we know about a William Patterson, or we know about Brown v. Board of Education, but we don’t know as much about Scottsboro or the Rosa Lee Ingram case, or we know about the NAACP, but we don’t necessarily know about the Civil Rights Congress.

And so I call this knowing and not knowing intellectual McCarthyism. And I think it’s important to understand because when we only study Black liberalism, or when we try to read everything through a Black liberal framework, we miss the broader transformative or counter hegemonic or liberatory project at the intersection of Black liberation and socialism.

We often teach about the impact of McCarthyism on Hollywood and the labor movement. It would be important to also consider the impact it had on the Civil Rights Movement — and what is taught about that history in K–12 classrooms. ■