Cross Burning Threatens Black Sorority at Georgia Tech in 1985

Reading by Janine Gomez

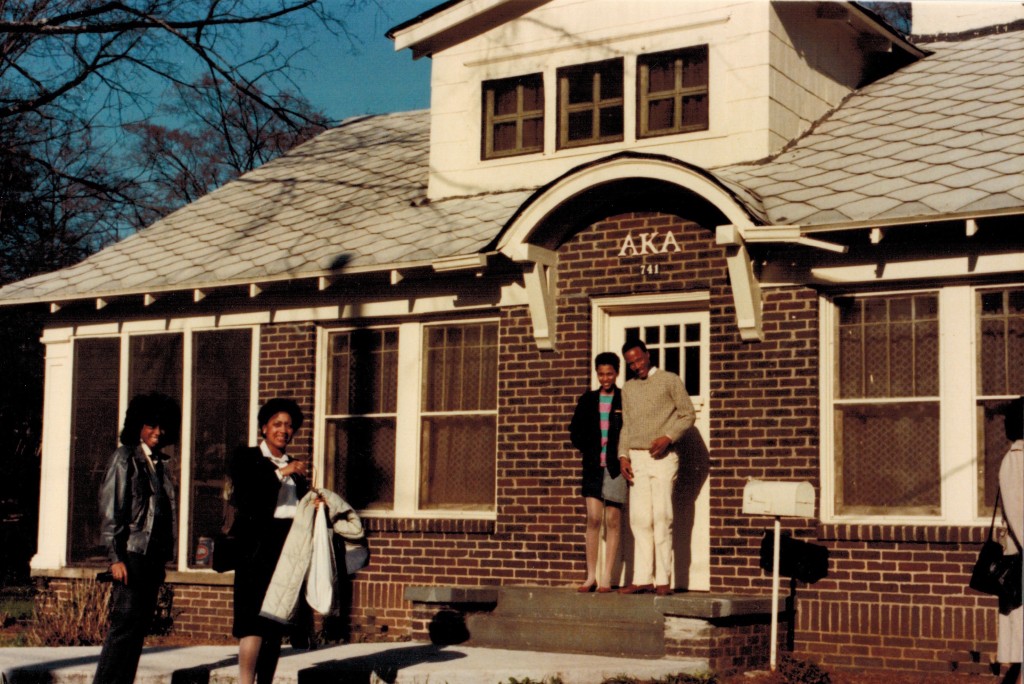

AKA house, March 1986. Janine Gomez standing in doorway.

I wish Smartphones had been invented when I saw that cross burning in front of our sorority house on the campus of the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1985. The response by school administration then is in stark contrast to the stand taken by the University of Oklahoma after the racist chant by Sigma Alpha Epsilon members was exposed. Justice would have been served, and my sense of safety and trust in humanity would still be intact.

It was an evening in the fall of 1985. As my roommate and I drove down the street towards the Alpha Kappa Alpha house in the center of campus one night, we noticed something glowing brightly in front of the house. I remember us leaning into the dashboard, as if somehow the posture would focus our eyes. We pulled up in front of the house to see a 4-foot cross in flames on the front lawn. I don’t even remember our conversation after that.

My brain couldn’t make sense of what my eyes saw, but I do remember, very clearly, what I felt. Terror. Sheer terror. Someone wanted us dead.

We went inside to alert everyone in the house. Our sorority sisters came out, and we stood in front of that blazing cross in silence. Dumbfounded. Someone went back inside to call the Campus Police. We also called our grad advisor, Dr. Dorothy Yancy, and I think everyone else we knew. Soon, people began to come to the house. The police came to take a report. Several of our male friends and Dr. Yancy stayed for the rest of the night, sleeping on floors and couches. Here’s the strange thing: The media didn’t arrive until the next morning. I think about how swiftly the video of the SAE members chanting on that bus was seen by thousands of people. It took time for news of the burning cross to travel off campus.

The terror I felt kept my body rigid, my mind blank. I wanted to call my parents, but it must have been after 1 a.m. by the time I thought about it. My sorors and friends who had stayed the night to protect us were talking about what to do, who might have done this. I said nothing. I just kept wondering how we were going to die, when would the men in white sheets and pointed hats come for us that night. Would they ride in on horses, as I had seen in the movies, or would they drive up in a pickup truck? Did their sons go to Georgia Tech? Would they be the ones to kill us?

Someone hated us, and they left the sign of a burning cross to let us know they were going to do us harm. I believed that. I knew there were racist people on campus — my first roommate in Glenn Dorm moved out two days after I arrived because I was Black. The Black students on campus socialized together because we knew we weren’t wanted at the white frat parties. Those SAE boys sang a song about there never being a nigger in SAE. We already knew that at Georgia Tech; we had no desire to be where we weren’t wanted. What I didn’t know until that night in 1985 was that we were not only excluded, but hated. But why?

After a couple of days of running into cameras and journalist on my way out the front door of the sorority house, I began to sneak out the back to get to class. Once in class, my mind continued to be flooded with questions that had nothing to do with the lecture for that day. Did the KKK exist on campus? Who would burn a cross on our lawn, and why? Was it someone in my class who did it? Was it him? Or him? Maybe it was a girl? Was it her? Was it that group of students sitting in the first row? Did someone in this class know who did it? It was my senior year, and I really needed to bring up my mediocre grades ASAP. I couldn’t focus on anything but finding out who burned that cross. My grades continued to suffer for a while.

The media stopped calling after a week, but the anger of the Black students on campus continued to rise. We gathered in one of the campus auditoriums several times, repeating the story and strategizing about how we would respond. We demanded meetings with the school president, Dr. Joseph Petit.

In the first meeting, Dr. Petit tried to blow off the incident. He said the burning cross was likely a “prank” played by students who meant no harm. The campus police reported no leads on who might have done it, and they weren’t really trying to spend time finding out. The sentiment of the white men in that room was very similar to that of Stephen Jones, who was hired to represent the local chapter of SAE at the University of Oklahoma.

Those meetings prompted me to focus my energy on graduating from Georgia Tech, and never stepping foot on that campus again. I buckled down and completed the Electrical Engineering program with an average GPA. I graduated in March 1986. It would be 27 years before I walked on that campus again. And to this day, I can’t count one white male as a friend. I don’t trust them.

Janine Gomez, 2014

Homecoming 2012 was my first time back on Georgia Tech’s campus. It was a surreal experience. Everyone was celebrating Homecoming. I tried, but I couldn’t help looking into the faces of the alumni I passed on the streets and wondering if they knew about that burning cross. I had fun reuniting with my friends, but I also continued to have questions about that night in 1985.

Smartphones and social media have brought to light what white people have excused as pranks and harmless shenanigans, and what police officers have viewed as necessary actions of self-defense. Victims of blatant racism and physical harm now have technology to give the world a glimpse into their pain, and they can use technology as a tool to take a stand and provoke action. Technology has acted as both a window and a mirror to raise our awareness that we are not in a “post-racist” society, and to bring us together globally to do something about it.

I carried the events of 1985 and that fear and distrust in my spirit for 30 years. Being a victim of racism and hatred is painful, no matter how blatant or violent. It cuts into one’s being and changes him/her forever. I just wish we had had Smartphones back in 1985. I’m so thankful for the brave use of them today.

RELATED STORIES

The Historical Roots of Fraternity Racism by Robert Cohen

Shades of Segregated Past in Today’s Campus Troubles by Leslie Harris

Campus Racial Incidents by The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education

Janine Gomez is a passionate educator living in Maryland. A longer version of this story is available in PDF here. Published by Teaching for Change, 2015.