Freedom’s Main Line: Louisville, Kentucky 1870-1871

Reading by Maria Fleming

Louisville Kentucky, mule drawn streetcar, Portland Ave. ca 1900.

On October 30, 1870, three men outside the Quinn Chapel in Louisville, Kentucky, made their way toward the trolley stand at Tenth and Walnut on the Central Passenger line. When the trolley stopped, each climbed aboard the near-empty car, dropped a coin in the fare box and took a seat.

It would have been a routine occurrence — three men catching a ride home after church on a Sunday afternoon — had the passengers been white residents of Louisville. But they were African American. And for Black city dwellers, riding a trolley was no ordinary act. It was a challenge to the entire social order.

As soon as the men entered the trolley car, a white passenger named John Russell told them to get off. The driver, too, demanded that they leave.

Robert Fox, an elderly mortician, quietly replied that he and his companions — his brother Samuel, who was also his business partner, and Horace Pearce, who worked for both brothers — had the same right to ride as whites.

In fact, the trio’s actions that day had been pre-arranged by Louisville’s Black community to test the legality of the streetcar companies’ segregation policies.

Under the policies, Black women were allowed to ride the trolleys, but on some lines, they were forced to take seats in the rear of the car. Black men were usually only permitted to ride on the small front platform with the driver, and on some lines, they couldn’t ride at all.

Nearly 300 African American men and women had gathered in front of Quinn Chapel that afternoon to show their support for what they hoped would lead to a legal decision striking down segregation on public carriers. Now a hush fell over the crowd as they waited to see what would happen.

The driver wasn’t about to argue the question of Black citizens’ rights with Robert Fox. Nor was he going to proceed on his route. He sent a message to the streetcar company’s central office that trouble was brewing and called out to other trolley drivers for assistance.

Before long, a cluster of white drivers surrounded the three Black men and began kicking them and shouting racial slurs. Then they dragged them off the trolley into the street.

The rough treatment of the men awakened the crowd in front of the chapel from its silence. Some men grabbed chunks of hardened mud and began hurling them at the trolley car and yelling threats at the drivers.

In the midst of the commotion, Pearce and the Fox brothers climbed back onto the car. They remained calm and composed, but now the men clenched stones in their fists. If the drivers attacked them again, they were ready to fight back.

The crowd shouted its support. “We’ll pay your fines!” “We’ll see you through this!” “Don’t budge a step!”

The superintendent of the Central Passenger Company came running up to the car. He said he’d return the men’s fares if they got off the trolley immediately. Still, they refused.

By now, five trolleys had backed up on the tracks behind the halted car. The crowd seemed ready to erupt in violence just as three police officers arrived on the scene. The officers quickly arrested the three men for disorderly conduct and hauled them off to jail.

THE OLD SOCIAL ORDER CRUMBLES

The streetcar protest in Louisville occurred during a time of tremendous upheaval in the South. The Civil War had ended just five years earlier. A period of Reconstruction was now underway as the federal government attempted to rebuild the former Confederate states economically, politically, and socially and rejoin them to the Union.

Although it had been a slave state, Kentucky had remained loyal to the Union during the war. As a result, it was not subject to the federal Reconstruction policies that sought to reshape Southern state governments and improve the status of the newly freed slaves. However, like the ex-Confederate states, Kentucky had also been transformed by the war and emancipation.

Before the Civil War, there had been no state-enforced separation of African Americans and whites in public places in the South. From white Southerners’ perspective, there had been no need. The institution of slavery clearly placed African Americans at the bottom rung of society and established white supremacy.

But following the war, Congress passed three new amendments to the Constitution abolishing slavery; extending citizenship rights to African Americans; giving Black men the right to vote; and guaranteeing all African Americans equal protection under the law.

The old Southern social order, built on the bedrock of slavery, had suddenly crumbled. Many whites panicked. They could not envision a society where former slaves had the same rights they did.

Southern legislatures quickly introduced laws, known as Black codes, that set limits on African Americans’ freedom. Under these codes, which varied from state to state, African Americans couldn’t own or rent farmland; they could be imprisoned for assembling in public, using insulting language or not having a job; and they could be whipped by white employers.

Some states’ and cities enacted statutes that called for segregated public transit, which until then had been a practice common only in Northern states.

As one Mississippi newspaper declared, “We must keep the ex-slave in a position of inferiority. We must pass such laws as will make him feel his inferiority.”

Another formidable obstacle stood in the path of African Americans seeking political and social equality: the Ku Klux Klan. Ex-Confederate soldiers and planters formed the Klan in 1865. The secret terrorist organization tried to drive African Americans — and whites sympathetic to their cause — away from the polls and thus keep them out of public office.

The Klan also sought to keep African Americans “in their place” socially. Newspapers throughout the South carried almost daily accounts of racial violence.

And yet, despite the political turmoil and ever-present threat of violence, Reconstruction was a period of tremendous hope and possibility for the newly emancipated slaves, as well as free men and women of color.

For two centuries, they had been struggling to break the chains of slavery and stand on equal footing with white Americans. Slavery was finally dead, and the federal government had acknowledged African Americans’ civil and political rights. Now they were determined to exercise those rights.

A LEGAL VICTORY

The Fox brothers and Horace Pearce arrived in court the day after their arrest, prepared to make a case that they were entitled to the same treatment on the streetcars as white passengers.

Col. John H. Ward, a white lawyer, defended the men. He pointed out that they had, in fact, been “exceedingly well behaved” during the incident, and thus the charge of disorderly conduct was not valid. The real issue, he said, was that the men had been refused a seat because of their race.

“It is a small matter to assess a fine of from five to twenty dollars for disorderly conduct,” Ward argued, “and that to us is no great thing; but it is a great thing for us to know whether or not we are to be debarred from all protection from injustice and wrong. They are good citizens … and they ask for simple justice and nothing more.”

The judge, however, refused to consider the broader issue that Ward raised. He ruled only that the men had indeed created a disturbance and fined them $5.

Louisville’s Black community, however, was not about to let the more pressing question of their rights go unanswered. Backed by the city’s African American leaders, Robert Fox decided to sue the Central Passenger Railroad Company for denying him access to its streetcars.

Because the state courts did not allow Black testimony, Fox filed his suit the following week in the U.S. district court in Louisville. During the winter, many African Americans boycotted city streetcars as they waited for the federal court to hand down its decision.

On May 11, 1871, the district court ruled on behalf of Fox. The monetary award was small — $15 — but it represented a huge symbolic victory for Louisville’s Black community.

Triumphant, Black men and women immediately began to test their right to ride. However, they soon found that the federal court was far more willing to recognize their status as equal citizens than Louisville’s white residents.

“PUT HIM OUT!”

The day of the ruling, a Black man boarded a car on Jefferson Street. When the driver demanded he get off, the man refused to move. The operator drove the car off the tracks. He, too, refused to move. For half an hour, the two men sat in silence.

Outside, tension mounted as a crowd of African Americans and whites began to gather around the car. Finally, the Black passenger stepped off the trolley, and the crowd dispersed. But the demonstrator had established a pattern for other “ride-ins” that would soon follow.

During the next three days, Black citizens boarded streetcars throughout the city. When they would not get off, drivers ran the trolleys off the tracks, refusing to proceed on their routes. Soon, cars began to back up on the trolley lines, clogging the streets and wreaking havoc on the city’s public transportation system.

Several times, the trolley operator and white passengers abandoned the streetcars when protesters wouldn’t leave. Black riders didn’t waste any time taking the operator’s place and driving the streetcar themselves.

Sometimes, the protesters were spotted with their feet up on the cushioned seats, smoking cigars as they cruised along the tracks and a throng of Black supporters cheered them on.

City and state officials denounced the court’s ruling and refused to enforce it. Louisville’s three local newspapers rebuked the protesters for stirring up trouble in an otherwise tranquil city.

Their editors promoted the idea of separate cars for Black riders as a way to restore peace. The African American community immediately rejected the suggestion.

Black passengers were committed to using non-violent resistance during the protest. Those participating in the “ride-ins” maintained a steely composure in the face of hostile white mobs and rough treatment. Sometimes drivers and white passengers tried to forcibly eject the demonstrators, grabbing them by their feet and dragging them from the cars.

On one streetcar line, a group of white riders threw a Black passenger out a window. Another time, a group of white newsboys beat a Black man attempting to board a car. Everywhere, Black and white onlookers clustered on street corners and spilled into the streets, watching and waiting.

On Friday, May 12, the demonstration reached a climax, with protesters staging “ride-ins” on every streetcar line in the city. As dusk fell, an angry white crowd gathered in front of the Willard Hotel.

There, a Black teenager named Carey Duncan quietly climbed onto a trolley. Duncan sat passively as he watched the mob swarm around the streetcar. Suddenly, they began to rock the car, trying to overturn it. Duncan grabbed hold of the seat and hung on for his life. The crowd roared: “Put him out!” “Hit him!” “Kick him!” “Hang him!”

On the sidewalk in front of the hotel stood Louisville’s chief of police. He watched as a gang of white teenagers climbed aboard the car and threatened Duncan, shouting insults in his face.

Still, Duncan didn’t move or make a sound. He stared straight ahead. The gang dragged Duncan from the car and began to beat him. Finally, Duncan’s resolve to remain impassive broke down, and he fought back.

By now, Black men and women had gathered in the street, too, and the police feared the mass of people was about to explode in violence. Several officers stepped in and grabbed Duncan and quickly broke up the crowd. Duncan was later charged with disorderly conduct. The youths who beat him went free.

After two days of clashes on city streets, the community’s nerves were frayed. Everywhere, tempers ran high, and a full-scale race riot threatened. Rumors spread that the federal government was sending troops to restore order. Louisville’s mayor quickly arranged for people on both sides of the controversy to meet.

“SIMPLE JUSTICE”

On Saturday, May 13, Mayor John George Baxter Jr. sat down with leaders in the Black community and their lawyers, representatives from streetcar companies and the chief of police to negotiate a settlement.

The companies’ owners had grown nervous that prolonging the battle over their segregation policies would hurt profits. They also recognized that given the current political climate in the South, with the federal government stepping forward to advance and protect African Americans’ rights, this was a fight that ultimately they couldn’t win.

They agreed to give in to the protesters’ demands. After a long struggle, Louisville’s African American citizens had finally attained “simple justice”: the right to ride the city’s streetcars without restriction.

Louisville’s African American community was jubilant. But in the decades to come, there would be many more battles to fight, in Kentucky and throughout the South.

In 1877, Reconstruction — and the promise of change it offered African Americans — came to an end. The federal government’s attention drifted away from the South and the nation’s racial problems.

New laws established by the South’s “redeemer” governments sought to fully restore white power and supremacy and eroded many of the advances African Americans had made during the Reconstruction era. By 1890, the Black codes had solidified into the system of racial separation and discrimination known as “Jim Crow.”

This system was given full legal sanction in 1896 through the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson, which said that the 14th Amendment was not intended to enforce social equality between the races.

The decision would not be reversed until 1954. In the meantime, “Jim Crow” was free to flourish in the South, not just on streetcars, but in schools, libraries, parks, hotels, theaters and other public facilities.

African Americans never ceased agitating for their rights, however. When a series of new laws were enacted in southern cities and states establishing segregation on streetcars in the early 1900s, a wave of protest swept through the region.

Black men and women held rallies, organized petition drives and planned legal attacks on the new laws. Between 1900 and 1906, in more than 25 southern cities, they boycotted transit companies to protest segregated streetcars. [Read “The Boycott Movement Against Jim Crow Streetcars in the South, 1900-1906” from the Journal of American History.]

The boycotts lasted from several months to several years. In many cities, African Americans established their own informal transit systems during the protests by enlisting the services of private carriages, hacks (horse-drawn “taxis”) and drays (carts and wagons used to haul goods).

In Houston, Texas, when a streetcar strike left whites without transportation in 1904, African American draymen took pleasure in roping off the rear section of their carts and posting signs that read “For Whites Only.”

Most of the boycotts failed, however. A few brought short-lived victories, but before long Jim Crow measures were always reinstated.

Only in Louisville were African Americans successful in keeping Jim Crow off city streetcars. There, too, whites repeatedly tried to re-segregate the trolleys.

But Louisville’s Black citizens fought the Jim Crow ordinances every time they were proposed and held onto their hard-won right to ride — even as segregation increasingly defined other aspects of city life.

Although African Americans throughout the South never stopped fighting segregation, it would take another half-century before they were able to stamp out Jim Crow.

Reprinted with permission from Learning for Justice. Fleming, Maria. 2000. "Freedom's Main Line: Louisville, Kentucky 1870-1871." Learning for Justice (originally Teaching Tolerance). A Place at the Table (p. 32 - 42). Montgomery, Alabama: Southern Poverty Law Center.

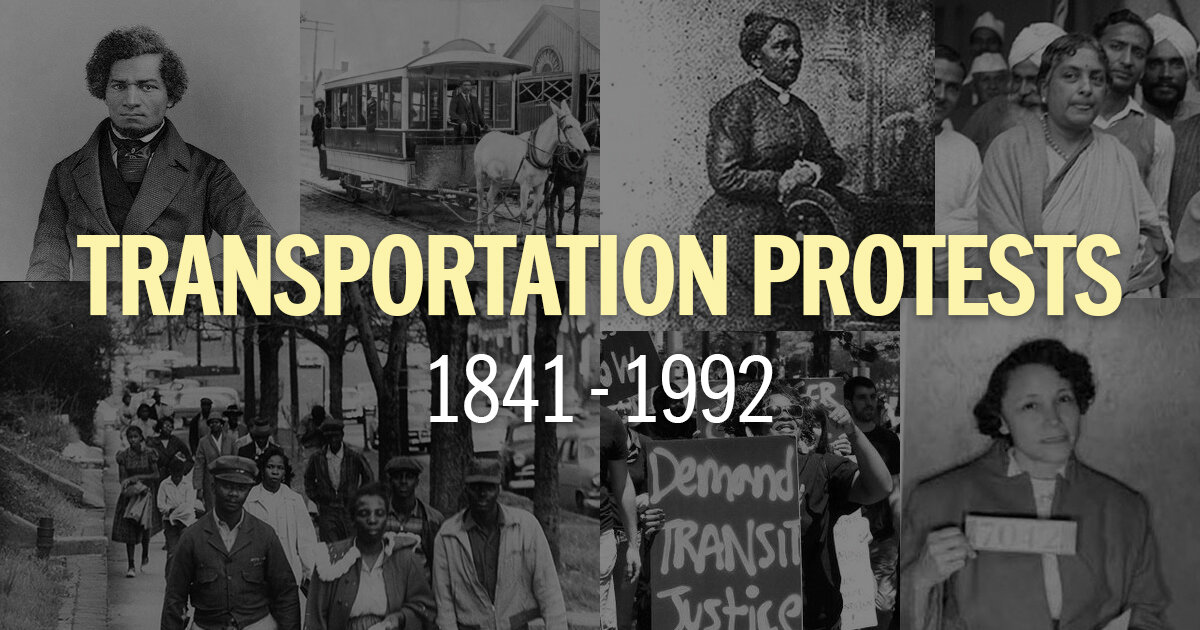

MORE TRANSPORTATION PROTESTS

See a list of dozens of protests on public transportation from 1841 to 1992.