From Freedom to Liberation: Politics and Pedagogy in Movement Schools

Reading by Daniel Perlstein

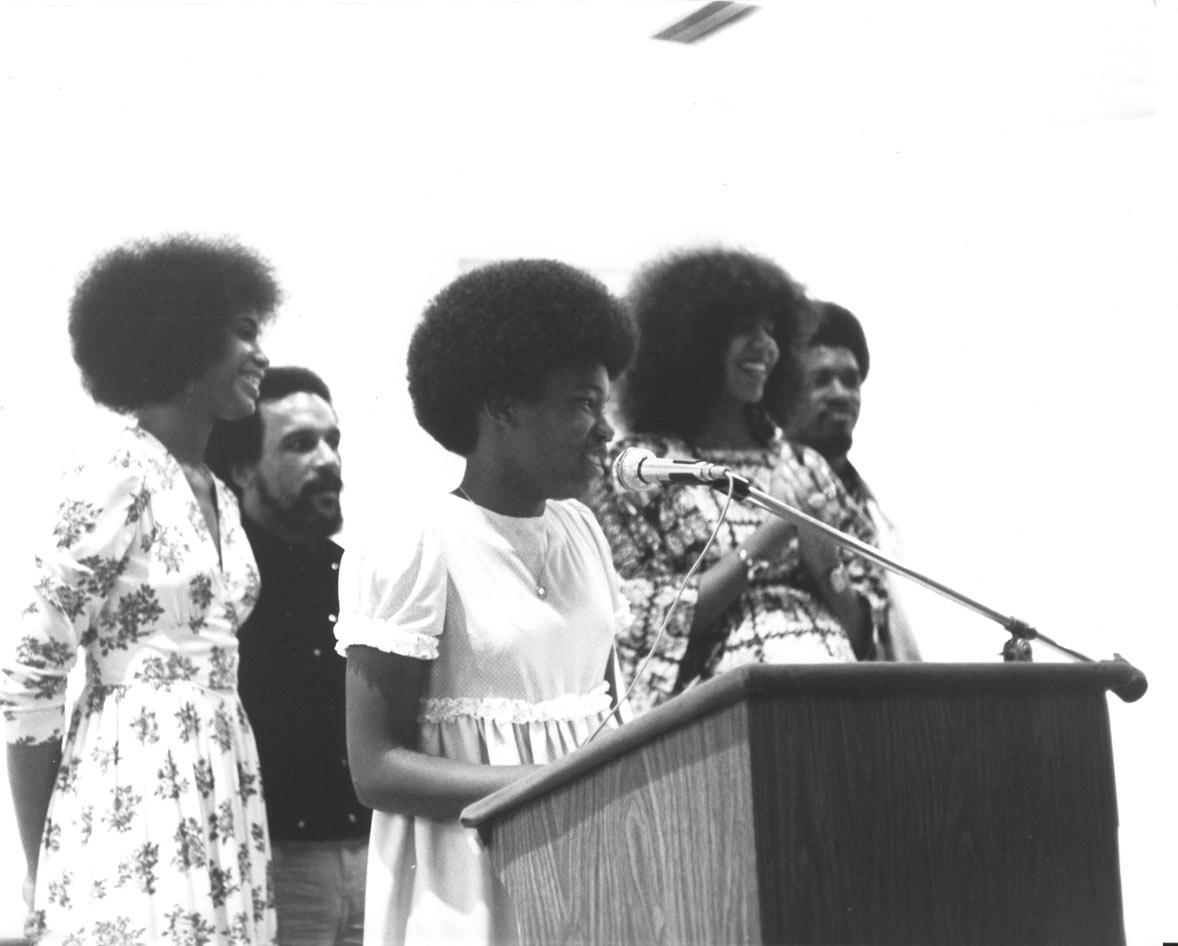

Oakland Community Learning Center

Evolving political conditions, goals, and analyses of American society continually reshaped Movement educational projects. Reflecting the Movement of the early 1960s, the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools, explained Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organizer Charles Cobb Jr., sought to help “young Negro Mississippians… articulate their own desires, demands, and questions.” Organizers’ faith in students’ ability to make sense of their world—their faith that American society was not irretrievably alien to students—inspired a “curriculum that begins on the level of the students’ everyday lives…. It is not our purpose to impose a particular set of conclusions. Our purpose is to encourage the asking of questions, and the hope that society can be improved.” Freedom Schools, in Cobb’s words, reflected “traditional liberal concepts and approaches to education.” Although the schools did not “grapple with the deeper flaws in education and society,” they contributed “to expanding the idea…that Black people could shape and control at least some of the things that affected their lives.”

In the years that followed the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer, the trust—in America and in students’ understanding—that infused freedom schooling began to dissipate. The Movement’s successes in dismantling Jim Crow offered little guidance in challenging the deeply rooted racial and economic oppression exemplified by conditions in northern ghettos. The belief that America itself was hopelessly racist discouraged both political mobilization through a language of shared American values and pedagogical approaches growing out of students’ American experience. A focus on critical analysis and self-expression among the voiceless was replaced by a desire to articulate a critique of society to the oppressed. Ironically, then, more radical critiques of American racism were matched by more traditional “banking” approaches to teaching. Whatever term one uses to describe the alternative to progressive pedagogy—teacher-centered, traditional, and direct instruction are popular—its essential characteristic is that a predetermined body of information or skills which students lack is delivered to them. Such an approach won increasing support from Black activists.

BLACK POWER, REVOLUTION, AND DIRECT INSTRUCTION

By the late 1960s countless Black activists, including many who had participated in the Mississippi Freedom Schools, found a model of revolutionary activism in the Black Panther Party. No group embodied the repudiation of assimilation and nonviolence or captured and transformed the imagination of African America more fully than the Panthers. Founded in 1966, the Panthers first gained fame through public displays of weaponry and militant confrontations with the police. Advocating a synthesis of Marxism and nationalism, the Panthers proclaimed the need to replace rather than reform American institutions.

A commitment to transmitting their revolutionary analysis led the Panthers to use a banking language in their educational proposals. The group’s 1966 Program demanded “education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society.” The main purpose of “the vanguard party,” Panther founder Huey P. Newton explained, was to “awaken...the sleeping masses” and “bombard” them “with the correct approach to the struggle.” “Exploited and oppressed people,” argued Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver, needed to be “educating ourselves and our children on the nature of the struggle and…transferring to them the means for waging the struggle.”

In the summer of 1968, San Francisco State instructor and Panther Minister of Education George Murray led efforts to develop the Panthers’ political education program for members, modeled on Mao’s efforts to educate Red Army troops in 1929. Political education classes became a central party activity, recalled Panther Chief of Staff David Hilliard, through which party leaders and theoreticians could “disseminate” their ideas to the cadre. In addition to classes for the cadre, the Panthers promoted political education in the community. Here too their goal was to transmit party ideology to Blacks living in an environment so oppressive that it precluded their discovering the truth.

Among the most prominent of the Panther educational programs was a network of “liberation schools” through which the Panthers taught children “about the class struggle in terms of Black history.” First established in 1969, the liberation schools are perhaps the closest counterpart from the late 1960s to the Freedom Schools of 1964. Both had an ephemeral existence, but both epitomized the political and pedagogical values of the most dynamic African-American activism of their day. Together, the two programs therefore illuminate the evolving relationship of politics and pedagogy.

The first liberation school opened in Berkeley, California, on June 25, 1969. There, elementary and middle school students were taught to “march to songs that tell of the pigs running amuck and Panthers fighting for the people.” Employing a curriculum “designed to...guide [youth] in their search for revolutionary truths and principles,” the Panthers taught the children “that they are not fighting a race struggle, but, in fact, a class struggle...because people of all colors are being exploited by the same pigs all over the world.” The children learned to work for the “destruction of the ruling class that oppresses and exploits,...the avaricious businessman...and the racist pigs that are running rampant in our communities.”

At the Panthers’ San Francisco Liberation School, “everything the children do is political.... The children sing revolutionary songs and play revolutionary games.” The entire curriculum contributed to students receiving a clear and explicit ideology. Teachers avoided lessons “about a jive president that was said to have freed the slaves, when it’s as clear as water that we’re still not free.” Instead, students learned the origins and history of the Black Panther Party and could “explain racism, capitalism, fascism, cultural nationalism, and socialism. They can also explain the Black Panther Party Platform and Program and the ways to survive.”

Black children “learned nothing” in public school, Panther Akua Njeri argued, “not because they’re stupid, not because they’re ignorant.... We would say, ‘You came from a rich culture. You came from a place where you were kings and queens. You are brilliant children. But this government is fearful of you realizing who you are. This government has placed you in an educational situation that constantly tells you you’re stupid and you can’t learn and stifles you at every turn so that you can’t learn.’” In the Panthers’ judgment, their own use of direct instruction was needed to counter the brutalizing impact of American schools and society.

In 1971 the Panthers built on the liberation school pedagogy with the establishment of an elementary school in Oakland for the children of party members. In addition to providing academic classes, Intercommunal Youth Institute offered students instruction in ideology of the party and engaged in field work, “distributing the Black Panther newspaper, talking to other youths in the community, attending court sessions for political prisoners, and visiting prisons.” The children also learned to march in the Panthers’ military uniforms.

Within a few years of the party’s founding, however, the Panthers’ politics and approach to education began to shift. Abandoning revolutionary aspirations, activists gradually returned to community organizing and rediscovered the progressive teaching methods of the Freedom Schools. As historian Tracye Matthews notes, the Panthers’ “militaristic style” diminished as women, many from relatively privileged backgrounds, played an increasingly prominent role in party activity. (The rise of women in the party owed a good deal to the successful government campaign to jail or kill the male leadership. Prosecutors and judges joined with local and national police agencies in anti-Panther operations, which included constant harassment and hundreds of illegal acts as well as assassinations.)

As grassroots organizing gained strength, the commitment to progressive pedagogy returned to activists’ educational work. “All you have to do is guide [children] in the right direction,” Berkeley liberation schoolteacher Val Douglas explained. “The curriculum is based on true experiences of revolutionaries and everyday people they can relate to.... The most important thing is to get the children to work with each other.” Activists contrasted the Intercommunal Youth Institute, where students were “regarded as people whose ideas and opinions are respected,” with public schools, where children who questioned the dominant ideology were “labeled troublemakers.”

For a few years, historian Craig Peck notes, the IYI mixed “vestiges of prior Panther ideological training” with “progressive educational modes.” The Panthers’ mix of progressive and transmissive pedagogies mirrored the ambiguity of their politics. As they swayed between revolution and reform, the Panthers were undecided as to whether the Black community had the capacity to articulate its own demands or whether it had to depend on a vanguard to reveal the truth about its situation.

Still, the IYI’s mission continued to shift from the training of future Panthers to the establishment of a “progressive school” that could serve as a model of a “humane and rewarding educational program” for poor urban youth. Its pedagogy evolved increasingly from the inculcation of revolutionary political theory toward open-ended lessons reminiscent of the earlier Freedom Schools. “The goal of the Intercommunal Youth Institute,” the party had come to believe, was “to teach children to think in an analytical fashion in order to develop creative solutions to the problems we are faced with.” IYI students, The Black Panther now told readers, receive “the greater portion of their education through direct experience.” The school used field trips, including ones to the zoo, an apple orchard, Mt. Diablo, and the trial of the San Quentin Six, to “teach the children about the world by exposing them to numerous learning experiences.”

In 1974, the IYI was renamed the Oakland Community School, further distancing it from its revolutionary Panther roots. In the words of OCS director Erika Huggins, the school offered poor Oakland youth “individual attention in reading, mathematics, writing, and really, an understanding of themselves and the world. To do so, the school relied on practical experience as a basis of our learning experience.” In the new OCS, the educator served “primarily as a demonstrator and a reference,” helping students to “draw their own conclusions.” Teachers, the OCS Instructor Handbook stressed, “do not give opinions in passing on information; instead, facts are shared and information discussed.... Conclusions are reached by the children themselves.” “In contrast to public school instruction, which consists mainly of memorization and drilling,” OCS, The Black Panther now maintained, “encourages the children to express themselves freely, to explore, and to question the assumptions of what they are learning, as children are naturally inclined to do.”

Like the Panthers’ earlier liberation schools, the OCS reflected activists’ egalitarian project of transforming the education and lives of poor Black youth. The Panthers’ flagship school and its educational ideals continued to reflect a political mission, but that mission was now framed as the incorporation of poor Black youth into the mainstream of American life rather than the abolition of an oppressive social order.

THE ABANDONMENT OF ACTIVISM AND THE ECLIPSE OF PROGRESSIVISM

The Panthers’ local organizing led to some influence in Oakland’s local politics, but these limited successes could not compensate for the atrophied aspirations they embodied. Activists’ embrace of a pedagogy like that of the Freedom Schools therefore proved to be as tenuous as their effort to construct a revolutionary curriculum had been. By 1974, the Panthers criticized not only the repressiveness of public schooling but also its failure “to adequately teach English or grammar.” At OCS, in contrast, students “recite consonant blends,” and study word endings, diacritical marks, and alphabetization.

By the end of the 1970s, Craig Peck notes, OCS “instructor handbooks reveal a minimal attention to Black and ethnic studies and, importantly, contain no references to the Black Panthers.” Moreover, rote education in basic skills continued to supplant progressive methods of instruction. Whereas IYI Language Arts classes had once focused on the works of Black authors, teachers were now directed to stress “phonics...handwriting...and language mechanics.” “In this country,” the handbook argued, “the ability to speak and read Standard English is essential.” The OCS justified its focus on “Standard English” with the observation that “language barriers have systematically been used to oppress Black and other poor people in the country.”

A social studies unit on California’s government suggests how much Panther hopes for political transformation had narrowed. The unit-plan objectives called for students to state who “the current governor of California is and what his job entails.” Whereas in an earlier era, the Panthers would have articulated the state’s role in policing the oppressed, the OCS instructor now evaluated students’ ability to state, “[t]he governor’s job is to carry out the laws of the state and make life better for people living in the state.” The conventionalism of the OCS curriculum reflected the Panthers’ diminished sense of the capacity of Blacks to determine their individual or collective destinies. Instead of “trying to build a model school, provide a real education to Black kids,” Panther chief Elaine Brown lamented, “right now, I think, we’re mostly saving a bunch of lives.”

OCS educators did employ peer tutoring, individualized instruction, and other progressive techniques. Moreover, the school served a community-building function in Oakland no matter what its pedagogy. Still, as the radical hopes of the late 1960s faded, the school abandoned the idea that students could either make meaning of their world or be instructed so as to understand and eliminate their oppression.

CONCLUSION

The ideal of encouraging “children to become autonomous...in the classroom setting without having arbitrary, outside standards forced upon them,” as Lisa Delpit has argued, often rings hollow for disenfranchised youth in oppressive schools. So too the varied approaches of Movement schools belie any pedagogy that reduces method to decontextualized technique. Despite their crucial differences, both the SNCC schools and the Panther schools offered students an alternative to the ideologies of racial supremacy and economic oppression that surrounded them. Both exposed students to the culture of power, but also initiated a critique of it. Both conveyed a transcendent sense of possibility, appropriate to their times. What distinguishes the Movement schools from most of public education is not, in the final analysis, the techniques they employed. Rather, at issue is whether curriculum and pedagogy would perpetuate racism and other forms of social inequality or would foster change. There is, then, no Movement approach to education without rebuilding the Movement.

© 2003 Daniel Perlstein