Literacy and Liberation

Reading by Septima P. Clark

Septima Clark (1898-1987) was a pioneer in grassroots citizenship education and lifelong teacher. In 1956, after 40 years of teaching, her contract was not renewed in South Carolina due to her refusal to resign from the NAACP. She developed literacy and citizenship workshops that were essential in the drive for voting rights and civil rights during the Civil Rights Movement. In this excerpt from “Literacy and Liberation” in Freedomways Magazine, she describes the role of the Highlander Folk School (now called the Highlander Research and Education Center).

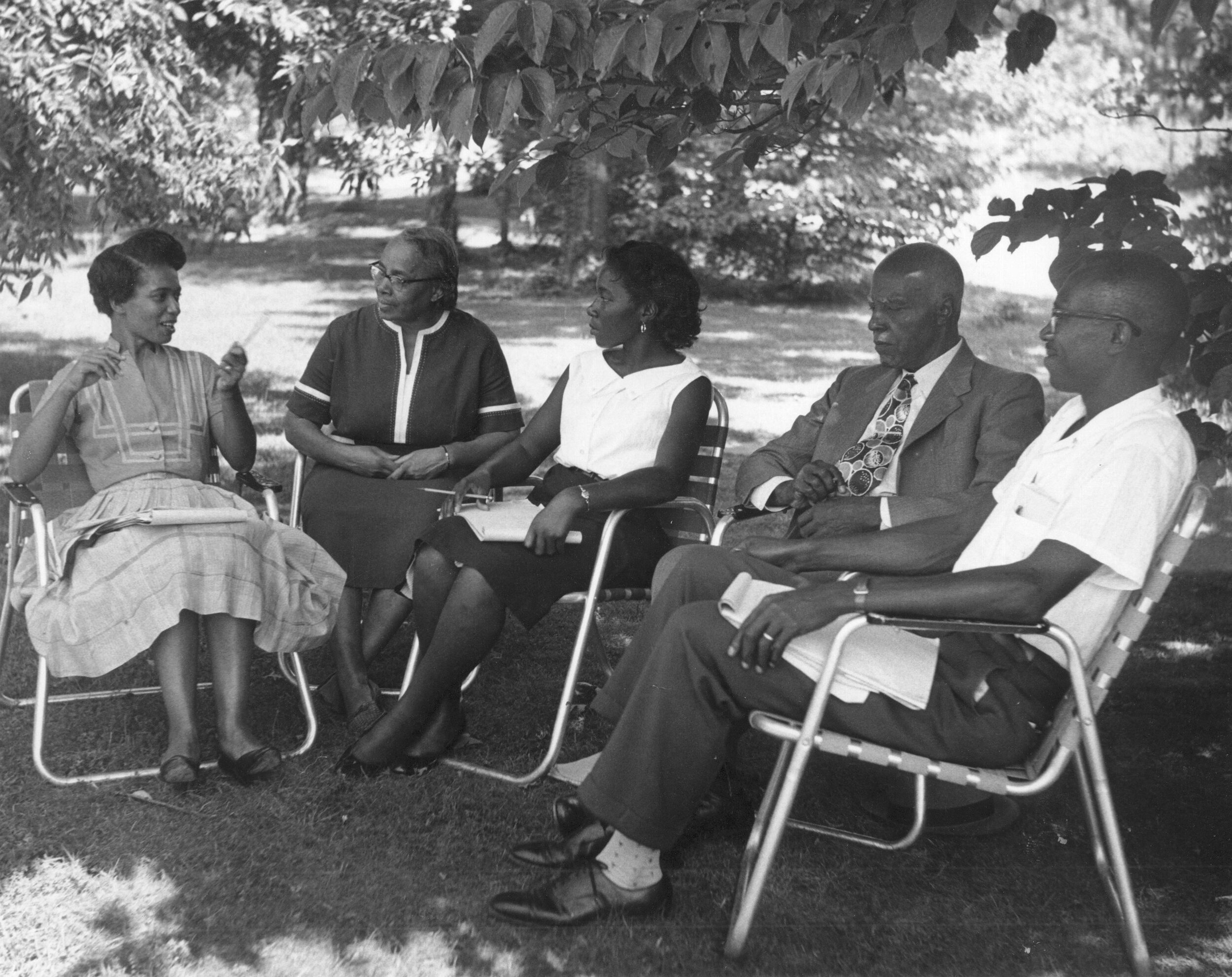

Septima Clark leading a discussion at Highlander Center. © Highlander Research and Education Center

The teacher wrote “Citizen” on the blackboard. Then she wrote “Constitution” and “Amendment.” Then she turned to her class of 30 adult students.

“What do these mean, students?” she asked. She received a variety of answers, and when the discussion died down, the teacher was able to make a generalization.

“This is the reason we know we are citizens: Because it’s written in an amendment to the Constitution.”

An elderly Negro minister from Arkansas took notes on a yellow legal pad. A machine operator from Atlanta, Georgia, raised his hand to ask another question.

This was an opening session in an unusual citizenship education program that is held once each month at Dorchester Center, McIntosh, Georgia, for the purpose of helping adults help educate themselves.

In a five-day course, those three words became the basis of a new education in citizenship for the Negroes and whites who attended the training session. Each participant left with a burning desire to start their own citizenship education schools in their own communities.

The program now being sponsored by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) has resulted in the training of more than 800 persons in the best methods to stimulate voter registration back in their hometowns. Their hometowns are located in 11 southern states from eastern Texas to northern Virginia. The program was transferred to SCLC from the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee.

I attended my first workshop in 1954. In 1955 I directed my first workshop and did door-to-door recruiting for the school. Unable to drive myself, I found a driver for my car and made three trips from Johns Island, South Carolina, to Monteagle, Tennessee. On each trip six islanders attended and were motivated. They became literate and are still working for liberation.

In 1954 in the South segregation was the main barrier in the way of the realization of democracy and brotherhood. Highlander was an important place because Negroes and whites met on equal ground and discussed their problems together.

There was a series of workshops on community services and segregation, registration and voting, and community development. Then it became evident that the South contained a great number of functional illiterates who needed additional help to carry out their plans for coping with the problems confronting them. Problems such as the following: six-year-old Negro boys and girls walking five miles on a muddy road in icy, wet weather to a dilapidated, cold, log cabin schoolhouse in most of the rural sections of the South. In cities like Charleston, South Carolina, children of that same tender age had to leave home while it was practically dark, 7:00 a.m., to attend an early morning session and vacate that classroom by 12:30 p.m. for another group in that same age bracket which would meet and then leave by 5:30 p.m. for home (nighttime during the winter months). These children would pass white schools that had regular school hours and enrolled fewer children. The Negro parents accepted this for many years. They did not know what to do about it. They had to be trained.

Highlander always believed in people, and the people trusted its judgment and accepted its leadership. It was accepted by Negroes and whites of all religious faiths because it had always accepted them and made them feel at home. The staff at Highlander knew that the great need of the South was to develop more people to take on leadership and responsibility for the causes in which they believed. It started a program designed to bring out leadership qualities in people from all walks of life.

Adults from all over the South, about 40 at a time, went there for the specific purpose of discussing their problems. They lived together in rustic, pleasant, rural surroundings on the top of the Cumberland plateau in a number of simple cabins around a lake, remote from business and other affairs that normally demand so much attention and energy. Though of different races and often of greatly contrasting economic or educational backgrounds, they rarely felt the tension that such differences can cause, and if they did, as it occurred sometimes, it was never for long. They soon became conscious of the irrelevance of all such differences. Each person talked with people from communities with problems similar to those of his own. Each discussed both formally and informally the successes and difficulties he’d had in his efforts to solve these problems in various ways.

The participants in the workshops included community leaders and civic-minded adults affiliated with agencies and organizations. They had a common concern about problems, but no one knew easy solutions. The issues then, as now, were among the most difficult faced by society. The highly practical discussions at the workshops challenged their thinking, which in turn helped them to understand the difficulties and, in most cases, steps were suggested towards a solution. They found out that it was within their power to take the steps necessary to meet with members of school boards. In Charleston County they asked for new schools and busses to transport their children. They staged a boycott to get rid of double sessions. They won! The immense value of a willingness to take responsibility and to act becomes clear when one sees what others have done, apparently through their willingness alone.

Literacy means liberation.

© 1964 by Freedomways Magazine. Reprinted with permission from Septima Clark, “Literacy and Liberation,” Freedomways Magazine, vol. 4, no.1 (Spring 1964).

Related Resource

Citizenship Schools: They Say I’m Your Teacher

Film. Directed by Lucy Massie Phenix and Catherine Murphy. 2019. 9 minutes. Documentary about Citizenship Schools.

In the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement, Bernice Robinson, a beautician from South Carolina, becomes the first teacher in the Citizen Education Schools, teaching African American adults to read to pass the voter registration requirements in the South.

They Say I’m Your Teacher is a documentary short about the Citizen Education Schools, created from the 16mm archives of the groundbreaking 1985 film, You Got to Move. The film, produced by The Literacy Project, can be streamed online in English and Spanish.

They Say I’m Your Teacher from Lucy Massie Phenix on Vimeo.

Also, in Spanish: Dicen que soy su maestra (9 mins)

Watch three more short films from the documentary You Got to Move: Stories of Change in the South.