The Limits of Master Narratives in History Textbooks: An Analysis of Representations of Martin Luther King

Reading by Derrick P. Alridge

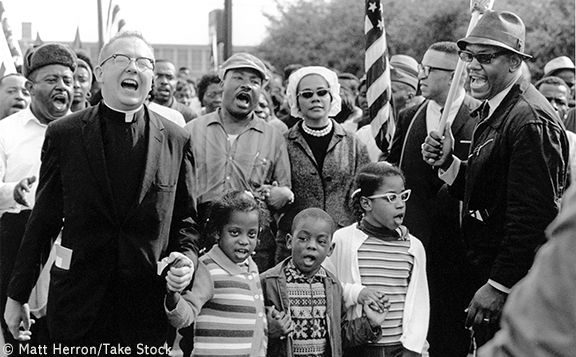

Selma to Montgomery March for voting rights in March, 1965. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King marching and singing with the Abernathy children, front, l to r: Donzaleigh Abernathy, Ralph David Abernathy III, & Juandalynn Abernathy. Left rear (fur hat) Ralph Abernathy. © Matt Herron/Take Stock

In this study, I argue that American history textbooks present discrete, heroic, one-dimensional, and neatly packaged master narratives that deny students a complex, realistic, and rich understanding of people and events in American history. In making this argument, I examine the master narratives of Martin Luther King Jr. in high school history textbooks and show how textbooks present prescribed, oversimplified, and uncontroversial narratives of King that obscure important elements in King’s life and thought. Such master narratives, I contend, permeate most history textbooks and deny students critical lenses through which to examine, analyze, and interpret social issues today. The article concludes with suggestions about how teachers might begin to address the current problem of master narratives and offer alternative approaches to presenting U.S. history.

During my years as a high school history teacher in the early 1990s, I observed the extent to which history textbooks often presented simplistic, one-dimensional interpretations of American history within a heroic and cele- bratory master narrative. The ideas and representations in textbooks presented a teleological progression from “great men” to “great events,” usually focusing on an idealistic evolution toward American democracy. Reflecting on these years, I also remember how heavily teachers relied on these textbooks, consequently denying students an accurate picture of the complexity and richness of American history.

U.S. history courses and curricula are dominated by such heroic and celebratory master narratives as those portraying George Washington and Thomas Jefferson as the heroic “Founding Fathers,” Abraham Lincoln as the “Great Emancipator,” and Martin Luther King Jr. as the messianic savior of African Americans. Often these figures are portrayed in isolation from other individuals and events in their historical context. At the same time, the more controversial aspects of their lives and beliefs are left out of many history textbooks. The result is that students often are exposed to simplistic, one-dimensional, and truncated portraits that deny them a realistic and multifaceted picture of American history. In this way, such texts and curricula undermine a key purpose of learning history in the first place: History should provide students with an understanding of the complexities, contradictions, and nuances in American history, and knowledge of its triumphs and strengths.

In his highly regarded book, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, James Loewen argued that “Textbooks are often muddled by the conflicting desires to promote inquiry and to indoctrinate blind patriotism” and that history is usually presented as “facts to be learned,” free of controversy and contradictions between American ideals and practice. According to Loewen, the simplistic and doctrinaire content in most history textbooks contributes to student boredom and fails to challenge students to think about the relationship of history to contemporary social affairs and life.

Loewen’s argument is not new. In 1935, historian W. E. B. Du Bois also noted the tendency of textbooks to promote certain master narratives while leaving out differing or controversial information about historical figures and events. As an example, Du Bois noted,

One is astonished in the study of history at the recurrence of the idea that evil must be forgotten, distorted, skimmed over. We must not remember that Daniel Webster got drunk but only remember that he was a splendid constitutional lawyer. We must forget that George Washington was a slave owner, or that Thomas Jefferson had mulatto children, or that Alexander Hamilton had Negro blood, and simply remember the things we regard as creditable and inspiring. The difficulty, of course, with this philosophy is that history loses its value as an incentive and example; it paints perfect men and noble nations, but it does not tell the truth.

The dominance of master narratives in textbooks denies students a complicated, complex, and nuanced portrait of American history. As a result, students often receive information that is inaccurate, simplistic, and disconnected from the realities of contemporary local, national, and world affairs. When master narratives dominate history textbooks, students find history boring, predictable, or irrelevant. If we continue this course of presenting history to students, we risk producing a generation that does not understand its history or the connection of that history to the contemporary world. We also deny students access to relevant, dynamic, and often controversial history or critical lenses that would provide them insight into the dilemmas, challenges, and realities of living in a democratic society such as the United States.

In this article, I examine how textbooks present heroic, uncritical, and cele- bratory master narratives of history. In doing so, I illustrate the master narratives that history textbooks present of one of America’s most heroic icons, Martin Luther King Jr. I illuminate how high school history textbooks promote King through three master narratives: King as a messiah, King as the embodiment of the Civil Rights Movement, and King as a moderate. Having shown how textbook master narratives portray King, I conclude by suggesting how teachers might move beyond the limitations of these narratives to offer students a more complex, accurate, and realistic view of figures and events in American history.

Methodology and Textbook Selection

[Footnotes in bold. Refer to full reading for footnote references.]

Literary analysis, a primary method in intellectual history, is the main methodological approach used for this study. According to historian Richard Beringer, literary analysis “involves reading source material and drawing evidence from that material to be used in supporting a point of view or thesis.” In most cases, such source material includes novels, short stories, or poetry, but it may also include nonfictional material. Beringer presents a straightforward approach to conducting literary analysis: (1) carefully read the literature, (2) identify emergent themes, (3) discuss and analyze the themes, and (4) and provide examples from the literature to support your conclusions. 6

The focal point of this investigation is the representation of Martin Luther King Jr. in the textbooks. King was chosen as a subject of analysis because he is a widely recognized figure in American history whose image has come to epitomize ideals of democracy, equality, and freedom in America.

To explore how contemporary textbooks, represent King, I examine six popular and widely adopted American history textbooks: The American Pageant (2002) by Thomas A. Bailey, David M. Kennedy, and Lizabeth Cohen; American Odyssey: The United States in the 20th Century (2004) by Gary B. Nash; America: Pathways to the Present (2005) by Andrew Cayton, Linda Reed, Elisabeth Perry, and Allan M. Winkler; The Americans (2005) by Gerald A. Danzer et al.; The American Nation: A History of the United States (2003) by John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes; and The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society (2004) by Gary B. Nash, Julie Jeffrey, et al. 7

According to the American Textbook Council, America: Pathways to the Present, American Odyssey, and The Americans are widely used in American high schools. Other textbook studies cite The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society as a popular textbook. I chose The American Nation because of its focus on political history and because it is a “bestseller” for Allyn & Bacon. The American Pageant has long been a popular textbook for high-level and advanced placement students in high school.8 In addition, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation cited The American Nation, America: Pathways to the Present, American Odyssey, and The Americans as four widely used textbooks in U.S. schools. 9

Highly respected historians wrote the textbooks examined in this study, and the information in them likely represents a broad spectrum of the ideas that are being conveyed about King in American classrooms.10 Furthermore, historian Van Gosse, who has conducted studies on American history textbooks, stated that textbooks are “remarkably similar in what is and what is not included; how an incident, person, or occasion is described; and in the sequence used to establish relationships among events.”11 Gosse’s assertion about the similarity of content among history textbooks supports my claim that these six textbooks may be considered representative of a much larger selection of high school history texts.

King as a Messiah

One way that textbooks package information for students is through the presentation of messianic master narratives. A messianic master narrative highlights one exceptional individual as the progenitor of a movement, a leader who rose to lead a people. The idea of messianism has long been a part of American culture and religion. Rooted in Judeo-Christian tradition and beliefs, the concept of a deliverer coming to Earth to free the masses from evil or oppression has been very appealing to Americans because of the predominance of Judeo-Christian beliefs and traditions in the United States.12

Perhaps more than any other figure in American history, the preacher has historically and symbolically been viewed as a messianic figure in the African American community. Historian John Blassingame traced this phenomenon to the institution of slavery, noting, “The Black preacher had special oratorical skills and was master of the vivid phrase, folk poetry, and picturesque words.”13 Given the resonance of preachers as messianic figures, it is understandable that Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., evoked a messianic image during his lifetime, one that the media and textbook publishers continue to promote today.14

King understood the power of symbolism and metaphor and purposefully evoked messianic imagery and symbolism in placing the struggle of African Americans within the context of biblical narratives. During his childhood in the 1930s and 1940s, young King came under the influence of his minister father, Daddy King, in Ebenezer Baptist Church, and many other great preachers throughout the South. These men influenced him with the biblical style of storytelling. The preaching that King was exposed to as a child was only one to two generations removed from the “slave preaching” that Black Americans heard during slavery, which was full of the passion and pain of a people in bondage.15 King studied and practiced the language, mannerisms, and locution of the Black preachers and began to reconfigure the religious metaphors and symbols for the struggles of his generation.16

King’s use of biblical language and imagery in both the spoken and written word also promoted a messianic tone and message that was appealing to a predominantly Christian nation such as the United States during the 1950s and 1960s. His merger of messianic and patriotic symbolism appealed to America’s patriotic sensibilities and its dominant Christian demography. King, like many political and religious leaders before and after him, understood the power of transcending racial ideological barriers by attempting to unify people under American and Judeo-Christian symbolism. 17 His references to the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, the Emancipation Proclamation, and a “promissory note,” juxtaposed with biblical references to “trials and tribulations,” “brotherhood,” and valleys, hills, and “crooked places” helped illuminate the images of Moses and the Exodus, Abraham Lincoln, and the Founders.

Given many historians’ focus on King as the central figure in the Civil Rights Movement, it is understandable that messianic symbolism continues to be associated with King. For example, the titles of some of the most popular books on King allude to messianic metaphor and symbolism. They include David Garrow’s Bearing the Cross; Stephen Oates’s Let the Trumpet Sound; Taylor Branch’s trilogy Parting the Waters, A Pillar of Fire, and At Canaan’s Edge; and Michael Dyson’s I May Not Get There with You. 18

History textbooks today also use messianic symbolism in portraying King as a messiah or “deliverer” during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the Birmingham campaign, and the March on Washington, and on the day before King was killed. For instance, four of the six textbooks portray King as an “unlikely champion” who would lead his people to the “promised land” during the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The unlikely champion reference parallels Judeo-Christian stories of Moses, the unlikely deliverer who was the son of an Egyptian pharaoh, and Jesus, the unlikely deliverer who was the son of a humble carpenter. The American Pageant, for example, states, “barely twenty-seven years old, King seemed an unlikely champion of the downtrodden and disenfranchised.” The American Odyssey says of King, “short in stature and gentle in manner, King was at the time only 27 years old.” The four texts referred to above also emphasize King’s youth or his privileged background as attributes that made him an “unlikely deliverer” of the Montgomery Movement. 19

Three of the six textbooks identify King’s Dec. 5, 1955, speech at Holt Street Baptist Church as a significant event during the boycott. 20 The emphasis on this particular speech further reinforces the focus on King as a messiah, because the speech is replete with symbolic messianic messages and metaphors of a young, unlikely, but charismatic savior. American Odyssey provides the most extensive coverage of the speech, including a picture of King delivering the speech, and quotes the following passage:

There comes a time when people get tired. We are here this evening to say to those who have mistreated us so long that we are tired — tired of being segregated and humiliated, tired of being kicked about by the brutal feet of oppression . . . If you will protest courageously and yet with dignity and Christian love, in the history books that are written in future generations, historians will have to pause and say “there lived a great people — a Black people — who injected a new meaning and dignity into the veins of civilization.” This is our challenge and our overwhelming responsibility. 21

King’s words reflected that of a young messiah trying to persuade his oppressed people to endure their trials and tribulations in the short term because their cause was just and because they could expect a better future. Such portrayals evoke the imagery of Jesus and Moses leading the masses and encouraging their people to endure temporary hardships for the long-term benefits of reaching paradise or the “promised land.”

Like many of King’s speeches, the Holt Street speech shows King in the messianic mission of delivering “God-inspired” words to the masses. America: Pathways, The Americans, and The American People also quote from this speech, reinforcing King’s strong words pertaining to Christian love and the liberation of the masses from the “brutal feet of oppression.” The Americans provides a block quotation from the speech and further reiterates its messianic symbolism, stating that “the impact of King’s speech — the rhythm of his words, the power of his rising and falling voice — brought people to their feet.” 22 The textbooks’ focus on a “messianic King,” even during his early life, denies students an opportunity to see King as a real person and as a young man who develops into a leader over time. Students also lose the opportunity to study the community leadership in Birmingham before King and to learn about the many ordinary citizens, whom King called his “foot soldiers,” who also played significant roles in the Civil Rights Movement.

All the textbooks that I examined also promote messianic imagery in their presentations of the Birmingham campaign and the 1963 March on Washington. For instance, most of the textbooks evoke messianic symbolism of the apostle Paul’s letters to the masses by printing, in part, King’s explanations to Christian ministers for breaking segregation laws and advocating for social justice. American Odyssey, for example, uses messianic symbolism by preceding King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” with the following statement: “Representing the opposition was King, who timed the demonstrations to include his arrest on Good Friday, the Christian holy day marking the death of Jesus.”23 Three other textbooks also provide block quotations from King’s “Birmingham Letter.” America: Pathways sets up its section about the Birmingham Letter and campaign by discussing King’s answer to a reporter who questioned him about how long he would stay in Birmingham. America: Pathways states that King “drew on a biblical story and told them he would remain until ‘Pharaoh lets God’s people go.’” 24

While The American Pageant and The American People both discuss the Birmingham campaign, neither mentions King’s letter. However, they more than compensate for their minimal messianic symbolism of King in Birmingham with their overly messianic portrayals of King at the March on Washington. The American Pageant and The American People further illuminate this imagery by providing a color picture of King waving before the multitude of people. The textbook images of King are reminiscent of Hollywood portrayals of Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount, in which Jesus is often portrayed with outstretched arms before a multitude of his followers. 25

America: Pathways quotes extensively from the “I Have a Dream” speech and provides messianic symbolism by featuring a photo of a long processional of marchers, also symbolic of the crowds that gathered to hear Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount. American Odyssey, The Americans, and The American Nation discuss and highlight the March on Washington to a lesser extent but still evoke similar examples of symbolism and imagery. However, The American Nation largely resists the more flowery or symbolic messianic language of the other texts.

Most of the textbooks address the last two major campaigns of King’s life — the march to Selma and his final days in Memphis. In all cases, the authors continue a type of messianic passion play, concluding with King’s famous “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech. The Selma campaign was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s (SCLC) march from Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery to further heighten the national intensity of the movement and to help push the Voting Rights Act of 1965 through Congress. American Odyssey provides a half-page black-and-white photo of a long processional of people marching from over the horizon, approaching from the Edmund Pettus Bridge outside of Selma on the way to the state capital of Montgomery, Ala. 26 This may easily be seen as symbolic of Moses and the Israelites crossing the Red Sea.

All the texts that mention the Selma march deliver an Exodus-type narrative in which King’s last “plague,” the march, eventually forced a “Pharaonic” Pres. Johnson to push for the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Moreover, the authors of America: Pathways believed that Johnson’s use of the language and symbolism of the Civil Rights Movement was so important that they quoted a passage from a speech given by the president shortly after the Selma march. America: Pathways quotes Johnson’s use of the civil rights anthem: “And . . . we . . . shall . . . overcome.” 27 Like the biblical pharaoh who eventually acknowledged the Hebrew God in Exodus, The Americans’ portrayal of Johnson’s co-option of “We shall overcome” conjures up the messianic story of Moses in the Exodus and parallels Pharaoh Rameses’s acknowledgement of the power of Moses’s God — in this case, the momentum and energy of the Civil Rights Movement.

Another symbolic messianic moment that four of the six textbooks present is King’s legendary “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, delivered on April 3, 1968, the night before his assassination. The Americans, America: Pathways, The American People, and American Odyssey provide quotations from this final speech, delivered while King was in Memphis helping striking garbage workers. The Americans also alludes to the night before King’s death as a kind of Gethsemane28 for King. It states that “Dr. King seemed to sense that death was near,” 29 while American Odyssey reports,

The night before his death King spoke at a church rally. He might have had a premonition when he said, “We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop . . . I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight . . . that we as a people will get to the promised land!” 30

The messianic master narratives of King in textbooks make him seem like a superhuman figure who made few (if any) mistakes and who was beloved by his Christian brethren. Textbooks largely fail to present King as experiencing any personal weaknesses, struggles, or shortcomings, nor do they convey the tensions that he encountered among other civil rights leaders and some Christian organizations. A more humanizing portrayal of King and the events surrounding him would address these issues and help us move beyond his larger-than-life image. Taking King out of the messianic master narrative and presenting him within the context of his full humanity provides a much more accurate, historically contextualized image of the man and what he stood for.

A critical presentation of King would provide insight into the life of an ordinary man who, along with others, challenged extraordinary forces and institutions to gain full citizenship rights for all. Such a strategy presents a more complex, genuine, and interesting knowledge base that would likely excite students about history. It might also make history “real” to students in a way that will help them see themselves as ordinary citizens who could bring about positive and progressive social change in American society. ■

Download full reading with sections on methodology, King as a messiah, King as the embodiment of the Civil Rights Movement, King as a “moderate,” what teachers can do, and footnotes.

© Teachers College, Columbia University. Teachers College Record Volume 108, Number 4, April 2006. Reprinted with permission from Derrick P. Alridge.