Mississippi at Atlantic City

Reading by Charles M. Sherrod

In 1964, a year after Birmingham’s fire hoses were unleashed on Black children and a year before the March from Selma to Montgomery, SNCC decided to upgrade their protracted work in Mississippi. The Movement needed to create a conflict that would arouse the nation’s (white) consciousness, so the idea of “Freedom Summer” was born.

Bob Moses and Fannie Lou Hamer were among those activists who birthed the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) that same spring. At the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City later that summer, the MFDP would protest the exclusion of African Americans from the Jim Crow state Democratic Party delegation. Freedom Summer and the MFDP were examples of Movement activists taking radical actions for what in the 21st century would be considered the most conservative reforms.

This report by SNCC veteran Charles Sherrod tells an engaging and profound story about the formation of the MFDP, the struggles faced by and within the African-American community, and the tremendous challenges yet to be addressed.

A nighttime rally outside the Atlantic City Convention Hall in support of seating the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Source: Wisconsin Historical Society

It was a cool day in August beside the ocean. Atlantic City, New Jersey, was waiting for the Democratic National Convention to begin. In that Republican fortress history was about to be made. High on a billboard, smiling out at the breakers, was a picture of Barry Goldwater and an inscription, “In your heart you knowhe’s right.” Later someone had written underneath, “Yes, extreme right.” Goldwater had had his “moment,”two weeks before, on the other ocean. This was to be L. B. J.’s “moment,” and we were to find out that this was also his convention.

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party had been working rather loosely all summer. Money was as scarce as prominent friends. A small band of dedicated persons forged out of the frustration and aspirations of an oppressed people a wedge; a moral wedge that brought the monstrous political machinery of the greatest power on earth to a screeching halt.

The Freedom Democratic Party was formed through precinct, county, district, and state conventions. An attempt to register with the state was frustrated. But the party was opened to both Black and white voters and nonvoters, for the state of Mississippi had denied the right to vote to thousands. Ninety-three percent of the Negroes 21 years of age or older in Mississippi are denied the right to vote. To show to the Convention and to the country that people want to vote in Mississippi, we held a Freedom Registration campaign. In other words, a voter registration blank from a northern state was used. Sixty-thousand persons signed up in less than three months. We presented our registration books to the Credentials Committee. Both the facts and the law were ably represented by our attorney, Joseph Rauh Jr., who was also a member of the Credentials Committee.

No one could say that we were a renegade group. We had tried to work within the structure of the state party. In fact, we were not only trying to be included in the state party, but we also sought to insure that the state party would remain loyal to the candidates of the national Democratic Party in November. We attended precinct meetings in several parts of Mississippi.

In eight precincts insix different counties, we went to polling stations before the time legally designated for the precinct meeting, 10:00 a.m., but were unable to find any evidence of a meeting. Some officials denied knowledge of any meeting; others claimed the meeting had already taken place. In these precincts we proceeded to hold our own meetings and elected our own delegates to the county conventions.

In six different counties where we found the white precinct meetings, we were excluded from the meetings. In Hattiesburg we were told that we could not participate without poll tax receipts, despite the recent constitutional amendment outlawing such provisions.

In ten precincts in five different counties, we were allowed to attend meetings but were restricted from exercising full rights; some were not allowed to vote; some were not allowed to nominate delegates from the floor; others were not allowed to choose who tallied the votes. No one could say that we had not tried. We had no alternative but to form a state party that would include everyone.

So 68 delegates came from Mississippi — Black, white, maids, ministers, carpenters, farmers, painters, mechanics, schoolteachers, the young, the old — they were ordinary people but each had an extraordinary story to tell. And they could tell the story! The Saturday before the convention began they presented their case to the Credentials Committee, and, through television, to the nation, and to the world. No human being confronted with the truth of our testimony could remain indifferent to it. Many tears fell. Our position was valid and our cause was just.

But the word had been given. The Freedom Party was to be seated without voting rights as honored guests of the Convention. The party caucused and rejected the proposed “compromise.” The slow and now frantic machinery of the administration was grinding against itself. President Johnson had given Senator Humphrey the specific task of dealing with us. They were desperately seeking ways to seat the regular Mississippi delegation without any show of disunity. The administration needed time!

Sunday evening there was a somewhat secret meeting held at the Deauville Hotel, for all Negro delegates. The MFDP was not invited but was there. In a small, crowded, dark room with a long table and a blackboard, some of the most prominent Negro politicians in the country gave the “word,” one by one. Then an old man seated in a soft chair struggled slowly to his feet. It was the Black dean of politics, Congressman Charles Dawson of Chicago.

Unsteady in his voice, he said exactly what the other “leaders” had said: (1) We must nominate and elect Lyndon B. Johnson forpresident in November; (2) We must register thousands of Negroes to vote; and (3) We must follow leadership — adding, “We must respect womanhood” — and sat down.

With that, a little woman, dark and strong, Mrs. Annie Devine from Canton, Mississippi, standing near the front, asked to be heard. The Congressman did not deny her. She began to speak.

“We have been treated like beasts in Mississippi. They shot us down like animals.” She began to rock back and forth and her voice quivered. “We risk our lives coming up here…politics must be corrupt if it don’t care none about people down there…these politicians sit in positions and forget the people put them there.” She went on, crying between each sentence, but right after her witness, the meeting was adjourned.

What a nightmare were they having? Here we were in a life-death grip, wrestling with the best political strategists in the country. We needed only 11 votes for a minority report from the Credentials Committee. They postponed their report three times; a subcommittee was working around the clock. If there had been a vote in the Credentials Committee on Saturday, we would have probably had four times as many votes as we needed; Sunday, two times as many; and as late as Tuesday, we still had ten delegates committed to call for the minority report. We had ten states’ delegations on record supporting us. We had at least six persons on the Credentials Committee itself who attended our caucus to help determine the best strategy. We had over half of the press at our disposal. We were the issue, the only issue at that convention! But the Black leadership at the convention went the way of the “Black” dean’s maxim: “Follow leadership.” The word had been given.

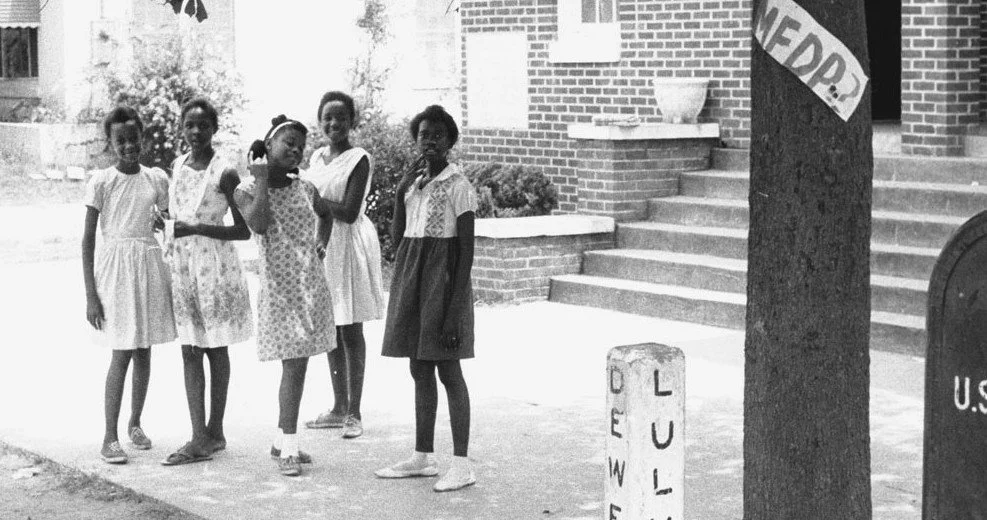

Five African-American girls from Hattiesburg, Mississippi pose for the camera in front of True Light Baptist Church during Freedom Summer, 1964. They are (from left to right) Otis Ruth Travis, Veronica Carter, Glenda Polk, Dorothy Jean Patton, and Joyce McGowan. Affixed to the tree near the girls is a handmade sign for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). © 1964 Herbert Randall Freedom Summer Photographs, McCain Library and Archives, The University of Southern Mississippi

The Freedom Party had made its position clear, too. They had come to the Convention to be seated in the place of the all-white party from Mississippi but they were willing to compromise. A compromise was suggested by Congressman Edith Green (D-Ore.), a member of the Credentials Committee. It was acceptable to the Freedom Party and could have been the minority report: (1) Everyone would be subjected to a loyalty oath, both the Freedom Party and the regular Mississippi party; (2) Each delegate who took the oath would be seated and the votes would be divided proportionally. It was minimal; the Freedom Party would accept no less.

The administration countered with another compromise. It had five points: (1) The all-white party would take the oath and be seated; (2) The Freedom Democratic Party would be welcomed as honored guests of the Convention; (3) Dr. Aaron Henry and Rev. Edwin King, chairman and national committeeman of the Freedom Democratic Party respectively, would be given delegate status in a special category of “delegates at large;” (4) The Democratic National Committee would obligate states by 1968 to select and certify delegates through a process without regard to race, creed, color, or national origin; and (5) The chairman of the Democratic National Committee would establish a special committee to aid the states in meeting standards set for the 1968 convention and that a report would be made to the Democratic National Committee and be available for the next convention and its committees.

It was Tuesday morning when the Freedom Democratic Party delegation was hustled to its meeting place, the Union Temple Baptist Church. You could cut through the tension, it was so apparent. People were touchy and on edge. It had been a long fight; being up day and night, running after delegations, following leads, speaking, answering politely, always aggressive, always moving. Now, one of the most important decisions of the convention had to be made.

At one o’clock it was reported that a group from the MFDP had gone to talk with representatives of the administration and a report was given; it was the five-point compromise. This was also the majority report from the Credentials Committee. There were now seven hours left for 68 people to examine the compromise, think about it, accept or reject it, propose the appropriate action, and do what was necessary to implement it. The hot day dragged on; there were speeches and speeches and talk and talk — Dr. Martin Luther King, Bayard Rustin, Senator Wayne Morse, Congressman Edith Green, Jack Pratt, James Farmer, James Forman, Ella Baker, Bob Moses. Some wanted to accept the compromise, and others did not. A few remained neutral, and all voiced total support whatever the ultimate decision. But time had made the decision. The day was fast spent when discussion was opened to the delegation.

The proposal was rejected by the Freedom Democratic Delegation; we had come through another crisis with our minds depressed and our hearts and hands unstained. Again, we had not bowed to the “massa.” We were asserting a moral declaration to this country that the political mind must be concerned with much more than the expedient; that there are real issues in this country’s politics and “race” is one.

One can logically move from this point to others. First of all, the problem of “race” in this country cannot be solved without political adjustment. We must consider the masters of political power at this point and acknowledge that the Blacks are not trusted with this kind of power, for this is real power. This is how our meatmaking and moneymaking and dressmaking and lovemaking are regulated. A readjustment must be made. One hundred counties where Blacks outnumber whites in the South need an example for the future. The real question is whether America is willing to pay its dues. We are not only demanding meat and bread and a job but we are also demanding power, a share in power! Will we share power in this country together in reconciliation or, out of frustration, take a share of power and show it, or the need for it, in rioting and blood?

The manipulation of power in our homeland is in white hands. The white majority controls the decisionmaking process here. At President Johnson’s “coronation” in Atlantic City there were no Blacks with power to challenge the position of the administration. Moreover, there was opposition by Blacks to any attempt to wield power against the administration’s position. There was no Black group supporting us; they had no power; they could show no power. But they had positions of power. One would suspect that it is part of the system to give positions meaningless labels and withhold the real power. This is the story of the bond between our country and its Black children.

In the South and the North, the Black man is losing confidence in the intentions of the federal government. The seating of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party would have gone a long way toward restoring the faith in the intentions of our government for many who believe that the federal government is a white man. Many Negroes believe that the government has no intention of sharing power with Blacks. We can see through the “token.” We have had a name for a white man’s Negro ever since any white man named one. We want much more than “token” positions or even representations. We want power for our people. We want it out of the country’s respect for the ideals of America and love for its own people. We need to be trusted, each for his own worth; this is why we are not chanting everlasting praises for the civil rights bill. We remember all the bills before. In fact, we remember the Reconstruction period. This time, we will be our own watchdogs on progress. We will not trade one slavery for another.

Secondly, we refuse to accept total responsibility for the conditions of race relations in this country. At the convention we were repeatedly told to be “responsible;” that Goldwater would benefit from our actions. We were told that riots in Harlem and Rochester and Jersey City and Philadelphia must stop. “Responsible” leaders have gotten up and called moratoriums in response to directives to be “responsible.” The country is being hurt by the riots, we are told admonishingly.

Who can make jobs for people in our society? Who runs our society? Who plans the cities? Who regulates the tariff? Who makes the laws? Who interprets the law? Who holds the power? Let them be responsible! They are at fault who have not alleviated the causes that make men express their feelings of utter despair and hopelessness. Our society is famous for its whitewashing, buck-passing tactics. That is one reason the MFDP could not accept the administration’s compromise. It was made to look like something and it was nothing. It was made to pacify the Blacks in this country. It did not work. We refused to adopt a “victory.” We could have accepted the compromise, called it a victory and gone back to Mississippi, carried on the shoulders of millions of Negroes across the country as their champions. But we love the ideals of our country; they mean more than a moment of victory. We are what we are — hungry, beaten, unvictorious, jobless, homeless, but thankful to have the strength to fight. This is honesty, and we refuse to compromise here. It would have been a lie to accept that particular compromise. It would have said to Blacks across the nation and the world that we share the power, and that is a lie! The “liberals” would have felt great relief for a job well done. The Democrats would have laughed again at the segregationist Republicans and smiled that their own “Negroes” were satisfied. That is a lie! We are a country of racists with a racist heritage, a racist economy, a racist language, a racist religion, a racist philosophy of living, and we need a naked confrontation with ourselves. All the lies of television and radio and the press cannot save us from what we really are . . . Black or white. It is only now that a voice is being heard in our land. It is the voice of the poor; it is the tongue of the underprivileged; it is from the lips of the desperate. This is a voice of utter frankness; the white man knows that he has deceived himself for his own purposes, yet he continues to organize his own humiliation and ours.

We have no political panaceas. We will not claim that responsibility either. But we do search for a way of truth. ■

© Charles Sherrod. Reprinted with permission from Charles Sherrod, “Mississippi at Atlantic City,” Grains of Salt (Union Theological Seminary, 1964).