A Lasting Impression: Student Travel Study

Teaching Reflection by Colleen Bell and Susan Oppenheim

In 1963, the police arrested a group of African American girls aged 12 to 15 when they tried to purchase tickets at the front entrance of a segregated movie theater as part of a civil rights protest in Americus, Georgia. They were transported to and held in an abandoned Civil War-era prison in Leesburg, Georgia, for 45 days. The “Stolen Girls” girls were never formally charged and their parents were not informed of their location by the police. This article documents what a group of 6th, 7th, and 8th graders and their teachers experienced when they traveled south to meet Carol Barner Seay and Sandra Mansfield, two of the Stolen Girls.

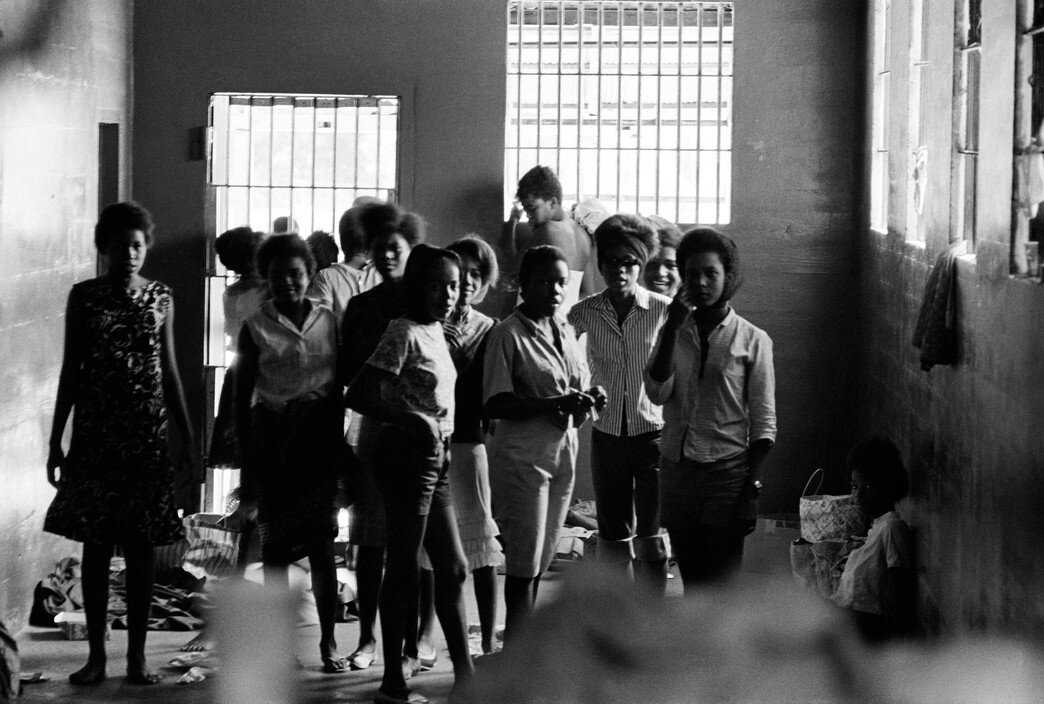

Arrested for demonstrating in Americus, teenage girls are kept in a Civil War-era stockade in Leesburg, Georgia. © Danny Lyon

Travel study — with learners of any age — requires planning and preparation. In this piece we demonstrate the impact on middle school students of studying history through the lives of young people and then traveling to meet some of those people, now elders, in communities where their courageous acts unfolded decades earlier. That impact is a powerful motivator for the preparation that makes it possible; we discuss the work of planning and preparing for travel at the end of the article.

This article draws on Susie Oppenheim’s teaching at Southside Family School (SFS) in Minneapolis and Colleen Bell’s observations and field notes from one of the school’s many Southern civil rights travel studies. Here we focus on one community of the many we have visited in Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Missouri.

Traveling South

Before we travelled south, we studied Danny Lyon’s images of various local movements. The students found a handful of photos especially engaging: teenage girls in a Civil War-era stockade where they were locked up for weeks. In one, a dozen Black faces look back at the photographer from behind the bars, many with shy smiles. Most are in pedal-pushers and short-sleeved blouses; a few wear sleeveless dresses. Their hair is pulled into braids or wrapped in scarves or worn in short afros. All but one stand barefooted, their clothes wrinkled.

Children had read accounts of their capture and detention. Because the Stolen Girls and their story has not been well-documented in civil rights history, children read one student’s personal narrative about the experience (Lulu Westbrook’s) and an article about a reunion of the Stolen Girls (Essence magazine, 1996).

The girls in the photo were arrested during a protest march in Americus, Georgia. It was the summer of 1963. Their cause: challenging Jim Crow brutality against Black people, especially the dehumanizing treatment of their parents, grandparents and community elders.

Now — 40-some years later — we’re on a bus, traveling down Highway 19 from Americus to the little town of Leesburg, where the stockade still stands. Two of the girls in that photo, now in their 60s, are riding in the bus with us. After decades of silence, Carol and Sandra have begun to share their stories publicly.

The woods press in toward the road. Carol holds the microphone close to her mouth and tells us they were arrested in the afternoon, held in Americus until sunset, and then transported out of town. She tells us:

They carried us to Leesburg at ‘blackdark’ so no one would see us or know where we were. The trees around the stockade were so thick you couldn’t see it from the road. And most of us hadn’t been beyond the outskirts of Americus so we had no idea where they were taking us.

The bus slows. Carol points to the right and our driver takes a tight turn onto a sandy yard with rain puddles here and there. A squat concrete building stands nearby. A sign over the door reads “Leesburg Public Works” but as we get closer, I see underneath it in stone, “Leesburg Stockade.” Two doors face the parking lot.

Sandra Mansfield with students outside the Leesburg stockade. Photo by Colleen Bell.

Sandra and Carol lead us through a door on the left side of the building into the space where they were detained for 45 days. The stockade is used for city storage now and we move in amongst the weed whackers and old tires and bags of Quikcrete and a garbage can holding rolled up American flags.

Sandra tells us that the other door leads to what was Mr. Countryman’s room. Most

folks called him “Pops.” He was a poor white man, an old guy, and usually he was the town dog catcher. While the girls were in the stockade, he was their guard.

Inside, there’s a musty smell and I feel a little crowded as the middle schoolers push toward Carol and Sandra. I edge back toward the door. Carol motions to the wall behind her where the dripping shower head was, and the nonfunctioning toilet, and the drain in the cement floor.

“We had three tin cups for all of us to use for drinking,” Carol tells us, “and the only water was dripping in that shower. It was warm.”

“Is anybody hot in here?” Carol asks. We are plenty warm, and not just because we’re from Minnesota where there’s still snow on the ground. It’s March in southwest Georgia and already in the 60s midday.

“Think about late summer,” she suggests. “It’s hot and sticky. There are bugs in here everywhere because the window glass is broken. Cockroaches on the half-cooked hamburgers we could not eat. Mosquitoes day and night. The smell of backed-up feces is awful because the toilet does not flush. We had to pee in the drain under the shower.”

Just at this moment, Sandra begins to tear up. Her body is shaking. Before she is able to push through the students to reach the door, she’s sobbing.

“Someone go with her,” Carol calls out. Susie and Kevin slide in alongside Sandra and guide her toward the sunshine.

Still inside the stockade, children begin asking questions. “What was the first thing you did when you got out?” Jada wonders.

Carol responds without pause: “I hugged my mama! And wanted to see my brother and sister.” She continues, “Mama took me to a doctor to be sure I had not ‘been touched.’ The doctor said I was still a virgin but I had a cold.”

“How did you keep your spirits up?” Brittany asks quietly, seeming to imagine herself locked up with the Stolen Girls.

“We sang freedom songs!” As Carol responds, her broad smile returns. We have already been singing with her and it’s easy to understand how singing freedom songs with friends can lift spirits.

Beyond the stockade door we hear Sandra talking with Susie and Kevin and Mona. She is laughing now. What a relief.

Before long we are on the bus and headed back toward the highway. We pass Pappy’s hotdog stand and kitty-cornered from it is the lynching tree. Carol remembers, “Black people called Leesburg ‘Lynchburg’ and the lynching tree still stands on this corner where it has always been.”

Understanding the Impact of Travel Study

First reactions to this encounter might be of the “how traumatizing for the children” variety. Susie Oppenheim’s response to that concern is anchored in four decades of social justice teaching and learning: unpleasant as it is, children deserve to know the truth of what results from an oppressive society. Children need to know this so they can establish their sense of themselves as powerful people, in the same way that Carol and Sandra did. We want children to see how a life connected to justice is a life of joy, and to understand strength in the human spirit, however young that spirit may be. We have witnessed how children feel empowered when they are equipped to take in difficult information, especially when that information is offered by people who were courageous children themselves.

On the bus after the stockade, Susie prompts students as she always does after a powerful experience:

Friends, I know that I did some crying today and my tears were about the horrific racism that very young people had to face. And my tears are also tears of gratitude to these young people who were changing their world. I would love everyone to think about what you’re feeling now. Just to feel it and to write about it. How does this feed into people’s attitudes about the power of children, and the reality of social change? Let’s just take five minutes as we ride along.

Kids — so much going on in their heads and hearts — are writing quietly. They are focused and compelled to reflect on their experiences. Gradually the pace of writing slows and students (and some teachers, too) come to the front of the bus and speak into the microphone. A handful of examples demonstrate what the Americus story has prompted in the children:

Sandra is my shero. I want to be as brave as she is.

And the sheriffs in Americus did the same thing Laurie Pritchett did in Albany: farming people out to nearby jails.

Sandra and Carol’s horrendous experience in that stockade propelled them into further activism. Sandra integrated the local high school a few years later. And they are both speaking now about their struggles for justice, in the ‘60s and now.

I like that Sandra is still fighting for justice . . . . with Mexican laborers in Americus.

Singing is a way to be in community.

As we travel on the bus, an activist community develops. Children and adults have been prepared to be deeply affected by the experience. Equipping travelers before a community visit — with readings and conversation — supports our ability to absorb more details and interact thoughtfully. Without knowing the story ahead of time and without understanding relevant historical context, the experience would be much less powerful. Given exposure to the story of the Stolen Girls and seeing that story as a chapter in southwest Georgia’s struggle, we have reflected on what it must have been like for the girls, and for their worried parents, during the time they were locked up. When we meet Carol and Sandra and hear their firsthand account, intellectual understanding and the sensory experience of the stockade produce emotional responses. When we understand more about these two women’s struggle, by extension we understand more about the struggle for justice wherever it is. Meeting people who were activists as young people deepens young learners’ connections with history.

Travel Study Preparation

Travel study is not an “add-on” or a special occasion at Southside Family School (SFS). Travel studies reflect the school’s mission. Every third year beginning in 1993, older students at Southside Family School have traveled south during spring break. Each of the nine trips has been designed so that young learners are prepared to talk with, learn from, and enjoy spending time with Movement veterans. Travel study is an extension of classroom learning in that we prepare for travel studies long before we board the bus.

Students participate in history club (an elective class focused on youth activism during the Civil Rights Movement) as well as regular humanities classes where literature and history are brought together.

Children are expected to pass three written tests of their knowledge with 80 percent accuracy.

Linking the “people’s history” with the dominant narrative of “discovery” is an important first step in understanding systems of oppression and resistance. Susie Oppenheim frames this history as beginning in 1505 with the transport of the first enslaved African to the Caribbean (rather than in 1619 with the establishment of slavery at the Jamestown colony). At the same time that children learn this history, they are developing an understanding of the impact of the attempted European conquest of North and South America.

Learners begin reading novels set in pre-Revolutionary War times through the 1930s (examples: War Comes to Willie Freeman, Forty Acres and Maybe a Mule, Runaway to Freedom). Protagonists in these initial readings are all young people. At the same time, Susie’s students read from chosen nonfiction accounts of slavery, the Great Migration, and sharecropping (examples from which excerpts come: The Warmth of Other Suns, Freedom’s Children, At the Dark End of the Street, Coming of Age in Mississippi, Walking with the Wind, Dumping in Dixie).

Students develop a critical perspective through a juxtaposition of traditional historical narratives that appear in textbooks alongside the more Black liberation-focused literature and history. This is possible in every decade for centuries. Reconstruction, for example, is often portrayed as a positive time for newly freed people in traditional history; in fact, the promise of the Reconstruction era was destroyed by the withdrawal of the U.S. government, leaving African American people to the whims of white supremacists who wanted their cheap labor. Middle school students begin to understand that they must consider the origins and authors of the history in question. As their critical perspective deepens, they recognize the importance of looking below the surface of whatever they read.

All of this elaborates the history of oppression and resistance and highlights systemic power relations in a way that traditional texts do not. Students role-play their understandings of texts (e.g., John Lewis preaching to his chickens), break into small groups to discuss readings, and do so with an eye on ordinary people challenging the status quo. Young people at Southside Family School also invite organizers and activists from the local community to share their knowledge and experience before and after travel studies (e.g., Minneapolis Black Lives Matter, Winona LaDuke, Dennis Banks, a local Welfare Rights Committee) and participate in rallies and demonstrations as part of their learning. In other words, we take the study of civil rights seriously but don’t see it as limited to U.S. civil rights study alone. We learn about many movements and we make connections across communities and through time. We recognize how the civil rights movement connects with people’s movements globally. We want to show how racism in this country works and the Southern civil rights movement is one of many places to look.

Learning continues when the time to travel finally arrives and we’re all on the bus. On the road, we read excerpts from personal narratives and local histories specific to the communities we are headed toward. These augment the grounding in history and literature that has been built in the classroom for the six months before departure. Students eagerly read aloud in small clutches with an adult participant on the bus. After small groups read, kids take turns responding to questions and highlighting key elements of the history. More opportunities to internalize the history come through larger conversations.

Each student who participates in travel study is required to present an independent project they have prepared in advance. Topics are selected by students and have spotlighted Bill Russell, Oscar Micheaux, Septima Clark, the Hawaiian island of Ni’ihau and the school-to-prison pipeline. Presentations are interspersed with other activities when we are traveling especially long distances. Sometimes pairs or trios of students put on skits anchored in our reading while the rest of the riders guess what is being re- enacted. At least once on each trip south we play civil rights jeopardy, often with teachers against the students. It is no contest. In our rooms at night, children journal on their own and conversations continue.

Over the years, it became clear that we needed a formal mechanism for sharing our learning with a broader audience. Susie developed a student-narrated slide show that includes historical images and photographs from the most recent trip into the South. The slide show — titled “Kids Make History” — begins with slavery and resistance to that slavery; it carries through Reconstruction and the long decades leading up to what we now call the Civil Rights Movement. Consisting of about 250 slides, it’s a 40- minute lesson in the fundamental role children and youth played in the freedom struggle. Oppenheim and her students revise the slide show after each triennial travel study with new people and locations.

As a teacher committed to learners owning their knowledge, making it their own, Susie notices when — after the trip — students’ desires to take action are heightened. Children are proud to share what they have seen and heard with parents, other students and friends. The slide show is also a mechanism for learners to actively teach people who are not aware of children’s involvement in the civil rights movement. Students share the slide show with a wide variety of audiences, beginning with other Southside Family School students and their families. Schools — elementary, middle, high schools, and colleges — and the occasional law firm or civic group invite SFS students to share their learning. We see our slide show as an opportunity for students to be teachers. We preface each presentation with our understanding that — throughout time and space around the world — kids have made history from Soweto, to uprising against Nazis in the Warsaw ghetto, to indigenous people’s resistance globally. Our shorthand for this idea is “kids make history.”

Concluding Observations, Goals, and Lessons

Travel study would not be possible without the many kinds of invisible work that support it. SFS staff and friends of the school stay in touch with veterans of the movement in the communities we visit. Teachers plan collaboratively with community members in the South, as well as researching new opportunities and accommodations in local communities we visit. Families and friends of the school pitch in with fundraising so that all students in grades 6–8 can participate at no cost. Teachers volunteer to spend the entirety of their spring break on the trip. It is absolutely critical that children have all the adult support they need during this 10-day travel study, and the teachers who volunteer are teaching/learning all day every day and chaperoning rooms with children at night. There are occasional bouts of homesickness, medications to be dispensed and always adults watching when we have access to a swimming pool or a park. There are no unsupervised spaces during travel study so the ratio of children to adults hovers around five to one. The issue of cell phones and other electronic devices as distractions has been settled by collecting students’ devices for portions of each day. When it’s time to focus on learning, someone walks the bus aisle with an open backpack and students drop their devices into it. When “down-time” comes again, everyone retrieves their device from the backpack.

The work of mapping our route through Southern communities has been Susie’s. Her teaching colleagues share her view of the civil rights history trip as Freirean (1970) curriculum writing, in which everyone learns and everyone teaches in a process of shared engagement.

As travel study volunteers, SFS teachers have witnessed the impact on learners of being in places where young people acted courageously, and of talking with folks who still live in the communities where their actions were staged. Standing in the Leesburg Stockade with Carol and Sandra, the mutual regard between these sheroes and the SFS students is unmistakable. Inspiration goes both ways, extending across generations, through the 24 years Family School has been traveling to talk with veterans of the movement, and over the hundreds of miles between our communities.

Suggested Reading

If We Could Change the World: Young People and America's Long Struggle for Racial Equality

by Rebecca de Schweinitz

Dumping In Dixie: Race, Class, And Environmental Quality by Robert D. Bullard

Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire

The Children by David Halberstam

Freedom's Children: Young Civil Rights Activists Tell Their Own Stories by Ellen S. Levine

Walking with the Wind: A memoir of the movement by John Lewis and Michael D'Orso

Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement by Danny Lyon

At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance--A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power by Danielle L. McGuire

Coming of Age in Mississippi by Anne Moody, Lisa Reneé Pitts, et al.

“Stolen Girls” by Donna Owens, Essence.

The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration by Isabel Wilkerson

On the Freedom Side: How Five Decades of Youth Activists Have Remixed American History

by Wesley C. Hogan

Mississippi's Exiled Daughter: How My Civil Rights Baptism Under Fire Shaped My Life by Brenda Travis with John Obee ■

© 2020 Colleen Bell and Susan Oppenheim. Printed with permission.