The Alabama Project

From CRMVet.org

Back in September of 1963, when four young girls were killed in the Birmingham bombing of the 16th Street Baptist church, Diane Nash Bevel and her husband James Bevel drew up a "Proposal For Action in Montgomery" — a plan for a massive direct action assault on denial of voting rights.

... we felt that if blacks in Alabama had the right to vote, that they could protect black children. ... [And we] promised ourselves and each other, that if it took twenty years, or as long as it took, we weren't going to stop working on it and trying, until Alabama blacks had the right to vote. So, we drew up that day, an initial strategy-draft for a movement in Alabama designed to get the right to vote. ... [My] job was to get on an airplane and have a meeting with Dr. King, and Fred Shuttlesworth, and encourage them to have a meeting with the staff to make a decision on what to do. — Diane Nash. [26]

Their draft plan called for building and training a nonviolent army 20-40,000 strong who would engage in large-scale civil disobedience by blocking roads, airports, and government buildings to demand the removal of Governor Wallace and the immediate registration of every Alabama citizen over the age of 21. When she presents the idea to Dr. King, she tells him, "..you can tell people not to fight only if you offer them a way by which justice can be served without violence." Rev. C.T. Vivian and SNCC & CORE activists support the idea, but King and most of his other advisors do not consider it feasible.

A month later, Diane and James Bevel again raise the plan, later called the "Alabama Project," at an SCLC board meeting. The general concept of some kind of "March on Montgomery" some time in the future is supported, but no date is set, no specific plans are made, and there is no consensus around the idea of militant direct action and massive civil disobedience. Instead, SCLC's attention is focused on continuing the struggle in Birmingham and the situation in Danville VA.

* White registration exceeds 100% because whites are retained on the voting rolls after they die or move away. Oddly, these dead or gone "tombstone" voters often manage to cast votes for the incumbents in each and every election.

In November of '63, the assassination of President Kennedy and the FBI's intensifying COINTELPRO attack on the Freedom Movement in general and Dr. King in particular disrupt all plans. In February of 1964, the Bevels again put their proposal for a prolonged nonviolent campaign before Dr. King, adding to it the idea of petitioning Congress to reduce the number of Alabama House members until all Black citizens can vote. An SCLC meeting in March supports the idea, though with Birmingham as the target city rather than Montgomery because of noncompliance with the agreement that ended the 1963 Birmingham protests. But no specific plans are made.

By the Spring of 1964, the so-called "white backlash" against rising Black assertiveness is swelling, and Goldwater's presidential campaign endorsing "states rights" is gaining ground. So too is George Wallace's campaign challenging LBJ in the Democratic primaries.

[In the context of the 1960s, "states rights" meant the right of individual states to impose mandatory racial segregation laws, restrict voting rights, and ignore (or "nullify") race-related Supreme Court rulings that state leaders disliked.]

Fearful of upsetting white voters who might support Goldwater, some northern liberals and conservative Black leaders call for a "moratorium" on all forms of direct action until after the November elections. When Brooklyn CORE calls for a freeway "stall-in" on the opening day of the New York World's Fair, many condemn the action. Dr. King refuses to join the critics:

Frankly, I have gotten a little fed-up with the lectures that we are now receiving from the white power structure, even when it comes from such true and tried friends as [Senators] Humphrey, Kuchel, Javits and Keating. ... [Somehow demonstrations] always become wrong and 'ill-timed' when they are engaged in by the Negro. ... Indeed, we are engaged in a social revolution, and while it may be different from other revolutions, it is a revolution just the same. It is a movement to bring about certain basic structural changes in the architecture of American society. This is certainly revolutionary. My only hope is that it will remain a nonviolent revolution. ... We do not need allies who are more devoted to order than to justice. ... Neither do we need allies who will paternalistically seek to set the time-table for our freedom. ... If our direct action programs alienate so-called friends ... they never were real friends. — Martin Luther King. [6]

In the U.S. Senate, opposition to the pending Civil Rights bill is fierce.

Instead of initiating a new voting rights campaign in Alabama, SCLC decides in late Spring to maintain pressure on Congress by throwing most of its strength into reinforcing the on-going anti-segregation campaign in St. Augustine, FL. The Bevels, James Orange, and a few other members of SCLC's small field staff, begin organizing in Birmingham, Montgomery and Tuscaloosa where a new direct action struggle erupts. But as a practical matter the "Alabama Project" is put on the shelf.

In November 1964, with the Civil Rights Act passed and Goldwater defeated, the Bevels again raise the "Alabama Project," arguing that the time has come to move on voting rights — which cannot be won without national legislation that eliminates "literacy tests" and strips power from county registrars. Such legislation, they argue, can only be won through mass action in the streets.

Meanwhile, in Selma, the injunction continues to stymie Movement activity. Long-time freedom fighter Amelia Boynton tells SCLC that if they are serious about voting rights in Alabama, they should come to Selma and defy the injunction. Rev. C.T. Vivian is sent to consult with DCVL and other Black leaders in Selma.

In late 1964, SNCC's finances were dwindling. This organization was also beginning to experience internal differences regarding philosophies. The organization's effectiveness was waning in Dallas County. ... Those of us who had the vision knew the Movement in Dallas County had to be elevated to another level. We had no choice. Representatives of the Dallas County Voter's League and several local citizens met at the home of Mrs. Amelia Boynton one evening. Mrs. Boynton was an extremely courageous woman. Her husband was the president of the Dallas County Voter's League before I was elected. The Courageous Eight invited representatives from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to the meeting at Mrs. Boynton's home. It was at this meeting that we formally invited SCLC and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to come to Selma. — Rev. F.D. Reese, DCVL [25]

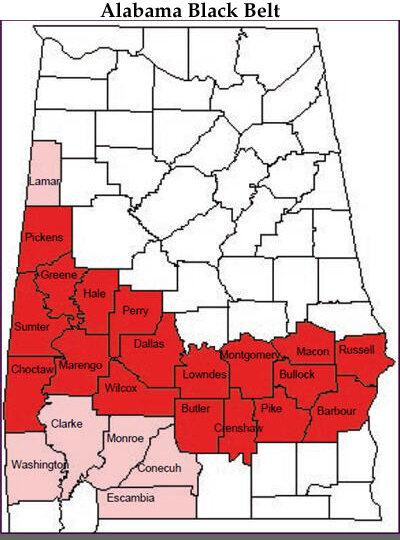

The decision is made. DCVL becomes the SCLC affiliate in Selma and SCLC commits to a voting rights campaign in Alabama with an initial focus on Selma and then expanding into rural Black Belt counties.

We wanted to raise the issue of voting to the point where we could take it outside of the Black Belt ... We were using Selma as a way to shake Alabama ... so that it would no longer be a Selma issue or even an Alabama issue but a national issue. — C.T. Vivian. [6]

Saturday, January 2, 1965, is set as the date for defying the injunction and commencing a massive direct action campaign. There are no illusions. Selma, Dallas County, and the Alabama Black Belt are bastions of white-supremacy and violent resistance to Black aspirations. Everyone understands that when you demand the right to vote in Alabama you put your life — and the lives of those who join you — on the line.

Visit CRMVet.org for more on Civil Rights Movement History 1965: Selma & the March to Montgomery.