Voting Rights History Quiz

We’ve all seen the iconic image of President Lyndon Johnson signing the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But what do we know of the history that led to the signing of the legislation?

When did the struggle for voting rights begin? Have voting rights always been restricted throughout U.S. history? Who is responsible for the Voting Rights Act getting passed?

Through this quiz and the answers that appear after each response, you can learn some of the history of the struggle for voting rights that is all too often omitted from the textbooks. Teaching for Change designed this quiz to challenge assumptions, deepen understanding, and inspire further learning about the voting rights struggle.

The quiz, used as a whole or one question at a time, can serve as a springboard for discussions and research. Please take the quiz, share it, and send us your feedback.

Each answer has links to books, articles, and/or websites. Learn more from The Voting Rights Act: Ten Things You Should Know by Emilye Crosby and Judy Richardson. Our publication, Putting the Movement Back into Civil Rights Teaching, provides readings and lessons on many issues addressed in the quiz.

Questions and Answers

Below are the questions and answers to our Voting Rights History Quiz.

Q1: Who was allowed to vote when the Constitution of the United States was first adopted?

Answer: It varied depending on what state you lived in

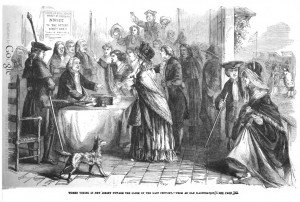

The Constitution, as originally drafted, did not specify who had the right to vote in federal elections, leaving those rules up to the states. In most states, only white, property-owning, Protestant Christian maleswere permitted to vote in the early days of the United States. In 1828 Maryland became the last state to allow white non-Christian men to vote, and in 1856, North Carolina became the last state to allow non-property owning men to vote.

In New Jersey, single, white, property-owning women were permitted to vote until 1807. White women gained the right to vote with the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

State constitutions protecting voting rights for free black men included those of Delaware (1776), Maryland (1776), New Hampshire (1784), and New York (1777), Pennsylvania (1776), and Massachusetts (1780). But by 1800, free blacks gradually began losing the rights they had “through intimidation, changing laws, and mob violence, whites claimed racial supremacy, and increasingly denied blacks their citizenship.” In 1857 the Supreme Court ruled in Dred Scott v. Sanford that “a black man has no rights a white man is bound to respect.” African-Americans were thus formally denied the right to citizenship and the right to vote.

All people of Asian descent were barred from becoming citizens, and thus voting rights, in 1790 by the Naturalization Act. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred immigration from China and specifically barred Chinese from becoming U.S. citizens. The Magnuson Act of 1943 repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act and allowed some Chinese residing in the U.S. to become citizens.

All Native Americans were granted citizenship by the Indian Citizen Act of 1924. However, Native Americans continued to be denied voting rights by law in several states, including Arizona and Colorado. In 1957 Utah became the last state to legalize the vote for Native Americans, but restrictions on voting including residency requirements (claiming Native Americans were not residents of the state if they resided on reservations), language tests, and other tests continued to restrict Native American’s right to vote.

In 1848 the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo made the lands now known as Arizona, California, New Mexico, Texas, and Nevada into U.S. territory. All Mexican persons within these territories were declared U.S. citizens, but simultaneously denied the right to vote by English proficiency, literacy, and property requirements along with violence, intimidation, and racist nativism.

In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution prohibited federal and state governments from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen’s “race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” but many people of color continued to be effectively disenfranchised.

Q2: During the Reconstruction Era (1865-1877), which of the following events did NOT occur in the South?

Answer: The federal government did NOT provide each male, freed from slavery, with forty acres and a mule.

While African Americans were owed reparations for the wealth they generated during centuries of enslavement, even the modest request of 40 acres and a mule was not provided. The repercussions of this lack of reparations remain today with the wealth gap based on race.

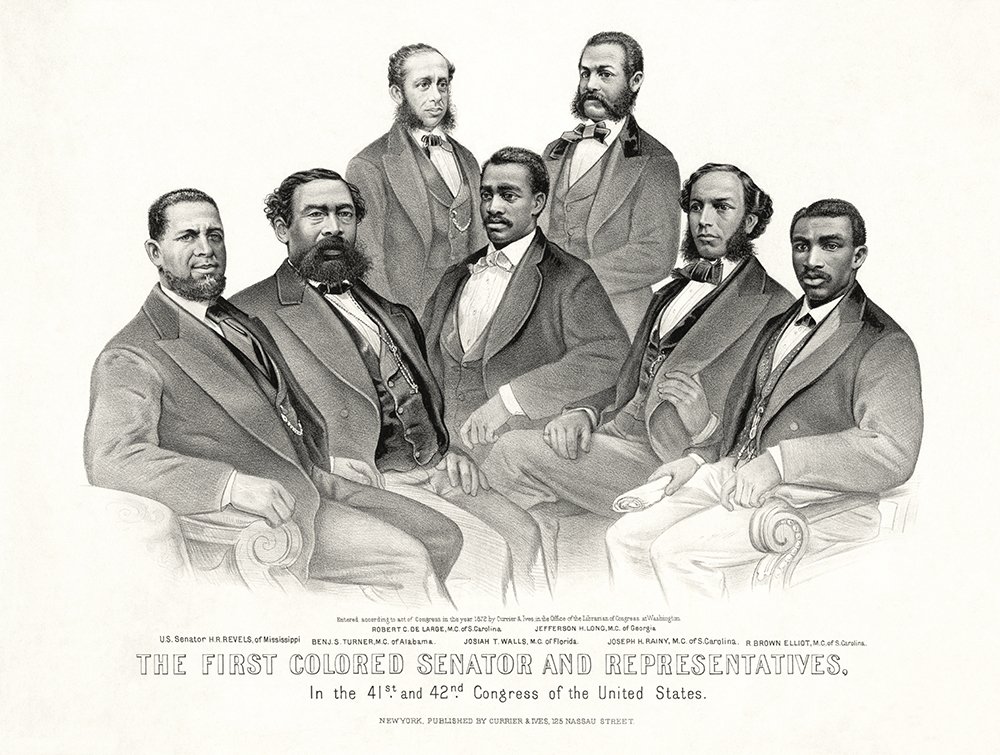

Often people taking this quiz select the answers about elected officials, assuming there were no African Americans elected to the U.S. Senate nor Congress until the modern Civil Rights Movement. Historical accounts have often downplayed the accomplishments of Reconstruction and Black civic engagement during that era. However, armed with the right to vote, Black men elected hundreds of Black legislators to state offices (as well as the 16 who served in the U.S. Congress), despite the harassment and violence against African Americans that preceded elections. The new Black politicians passed ambitious civil rights and public education laws. A total of 265 African-American delegates were elected, more than 100 of whom had been born into slavery. In all, 16 African Americans served in the U.S. Congress during Reconstruction; more than 600 more were elected to the state legislatures, and hundreds more held local offices across the South.

John Roy Lynch

Southern whites frustrated with policies giving people who had been enslaved the right to vote and hold office increasingly turned to intimidation and violence as a means of reaffirming white supremacy. The Ku Klux Klan targeted local Republican leaders and African Americans who challenged their white employers, and at least 35 Black officials were murdered by the Klan and other white supremacist organizations during the Reconstruction era.

For example, in 1870, John Roy Lynch joined the first group of Black representatives elected to Mississippi’s state legislature. He was 22 years old. By age 25, Lynch was the first African American from Mississippi to sit in the House of Representatives. Merely 10 years prior, Lynch had been enslaved. Lynch spent the last years of his life trying to correct the negative view of Reconstruction that prevailed in the U.S. by the early 1900s. In 1913, he wrote The Facts of Reconstruction, an autobiographical defense of the period. It wasn’t until 1987, more than a hundred years after Lynch’s last term in Washington, that Mississippi elected another Black representative to the U.S. Congress.

Learn More

American Experience Reconstruction: The Second Civil War (PBS)

Freedom’s Unfinished Revolution. By Eric Foner. New York: The New Press, 1996.

Freedom Road. By Howard Fast. New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1995.

The Case for Reparations. By Ta-Nehisi Coates. The Atlantic. June 2014 issue.

Reconstructing Democracy: Grassroots Black Politics in the Deep South After the Civil War. By Justin Behrend. University of Georgia Press. 2015.

Q3: During most of the 20th century, African Americans were prevented from voting by:

Answer: All of the above

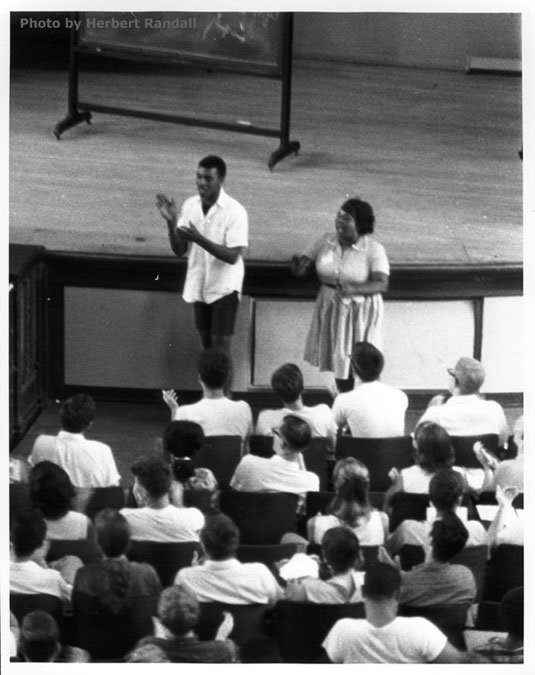

Gracie Hawthorne, volunteer for the 1964 Freedom Summer campaign to register voters in Mississippi. Photo by Herbert Randall.

After the Civil War, many African Americans took grave risks to exercise the right to vote, encountering relentless and multifaceted white resistance. While there were important pockets of black voting strength in the South (primarily in urban areas) during Reconstruction, it was not until the mid-1960s that the Civil Rights Movement was able to turn the tide against black disenfranchisement decisively.

One of the best ways to learn about the grassroots work of the Civil Rights Movement is to read the accounts of voter registration campaigns, including the role of Freedom Schools. Here one can learn about the strength and determination of the people who risked their lives to exercise their legal right to vote.

Learn More

The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow. Documentary film and website on the Jim Crow era in U.S. history.

“SNCC: The Battle-Scarred Youngsters.” By Howard Zinn in The Nation, October 5, 1963. A report from the front lines of the civil rights battle in Greenwood, Mississippi–a very dangerous place to be. Written in response to the March on Washington, this article provides chilling interviews with young activists who had been jailed for promoting the democratic practice of voting. Read online here.

On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Trail. By Charles E. Cobb, Jr. A useful reference to find the history of the freedom struggle in communities across the United States.

Civil Rights Movement Veterans website. This website is created by Veterans of the Southern Freedom Movement (1951-1968). It is where, as they explain, “we tell it like it was, the way we lived it, the way we saw it, the way we still see it. With a few minor exceptions, everything on this site was written, created, or spoken by Movement activists who were direct participants in the events they chronicle.

Education and Democracy. Online description of the role of Freedom Schools in the campaign for voting rights. Includes full Freedom School curriculum.

Q4: Which of the following happened to Fannie Lou Hamer after she took the voter registration test in Mississippi in 1962?

Answer: All of the Above

Fannie Lou Hamer

When people registered to vote in Mississippi, local newspapers were required to print the names and addresses of prospective voters, alerting their employers (who in many cases also owned their homes) and those prepared to use violence.

When Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer took the registration test in August 1962, white officials did not wait for the newspaper. By the time she had returned home, her landlord had left word with her family that she would have to remove her name from the list or leave her home and job the next day. She left that night, but the harassment continued. Within the next year, she had been shot at, charged hundreds of dollars on a water bill, even though she was living in a home without running water, and was viciously beaten in jail.

In the video interview below, Mrs. Hamer recounts her eviction from the Marlowe Plantation for attempting to register to vote. The clip is from the film We’ll Never Turn Back by Harvey Richards.

Mrs. Hamer did not shy away from the dangers of challenging segregation and the denial of voting rights in Mississippi. “I’m gonna be standing up, I’m gonna be moving forward, and if they shoot me, I’m not going to fall back, I’m going to fall 5 feet 4 inches forward.”

Sources: The Voting Rights Act: Ten Things You Should Know and SNCC Digital Gateway.

Learn More

Standing on My Sisters’ Shoulders (Film). One of the best films on the Civil Rights Movement, this award-winning documentary reveals the movement in Mississippi in the 1950s and 60s from the point of view of the courageous women who lived it — and emerged as its grassroots leaders.

This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer. Award-winning biography of black civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer.

Fannie Lou Hamer: Profile of Fannie Lou Hamer on the SNCC Digital Gateway website.

Q5: Which of the following individuals were murdered for pursuing their constitutional right to vote?

Answer: All of the above and many more.

Herbert Lee: On Sept. 25, 1961, voting rights activist Herbert Lee was shot and killed by E.H. Hurst, a member of the Mississippi state legislature, at a cotton gin in Liberty in front of about a dozen witnesses. Lee, a farmer, left behind his wife and nine children. Louis Allen, one of the witnesses in Lee’s murder, eventually told the FBI that Lee was shot by Hurst without any provocation. On Jan. 31, 1964, Allen was shot to death on his own driveway. Neither the Lee nor Allen murders have been prosecuted. More on SNCC Digital Gateway. Here is a classroom lesson on the murders of Lee and Allen from Teaching for Change.

Rev. George W. Lee, one of the first Blacks registered to vote in Humphreys County, Miss. used his pulpit and his printing press to urge others to vote. Lee was head of the Belzoni, Miss. NAACP. Lee was murdered on May 7, 1955. One of the people sent to investigate his murder was Medgar Evers, who was murdered on June 12, 1963. Rosebud Lee, decided to hold an open-coffin ceremony for her late husband. This decision planted the seeds for a similar decision by Mamie Till-Mobley, Emmett Till’s mother. Read more about Lee’s life and murder on the Miss. Civil Rights Project and in a chapter from the book Where Rebels Roost…Mississippi Civil Rights Revisited.

Lamar Smith, a 63 year old farmer and World War II veteran was a voting rights activist and a member of the Regional Counsel of Negro Leadership. On August 2, he had voted in the primary and helped get others out to vote. There was a run-off primary scheduled for August 23, and , on August 13, Smith was at the courthouse seeking to assist Black voters to fill out absentee ballots so they could vote in the run-off election. He was shot to death in the front of the courthouse in Brookhaven, Lincoln County, Mississippi at about 10 am. Learn more.

Jimmie Lee Jackson: Jackson’s grandfather, during the demonstrations that day at the county jail for the release of SCLC worker James Orange, was being beaten by the police, and Jackson stepped in to protect him, pulling him inside a café. The police shot Jackson in the stomach inside the café. Jackson fled to the street, where police continued to beat him. Eight days later, he died. The police officer responsible was not brought to justice until 2007, and only served a few months in prison. Jackson is included in the Teaching for Change lesson, Stepping into Selma.

Learn More

I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. This momentous work offers a groundbreaking history of the early civil rights movement in the South.

SNCC Digital Gateway: This digital gateway draws in documents, photographs, and audiovisual materials found at Duke and other SNCC-related collections in repositories across the country and uses them to chronicle the historic struggles for voting rights that youth, converging with older community leaders, fought for and won.

A Chronology of Violence and Intimidation in Mississippi Since 1961 (PDF).

Civil Rights Martyrs. A chronology prepared by the Southern Poverty Law Center that briefly describes the lives of individuals who lost their lives in the struggle for freedom during the modern Civil Rights Movement (1954-1968).

Q6: What actions did the FBI take that had the greatest impact on the daily struggle for voting rights during the mid-20th century Civil Rights Movement?

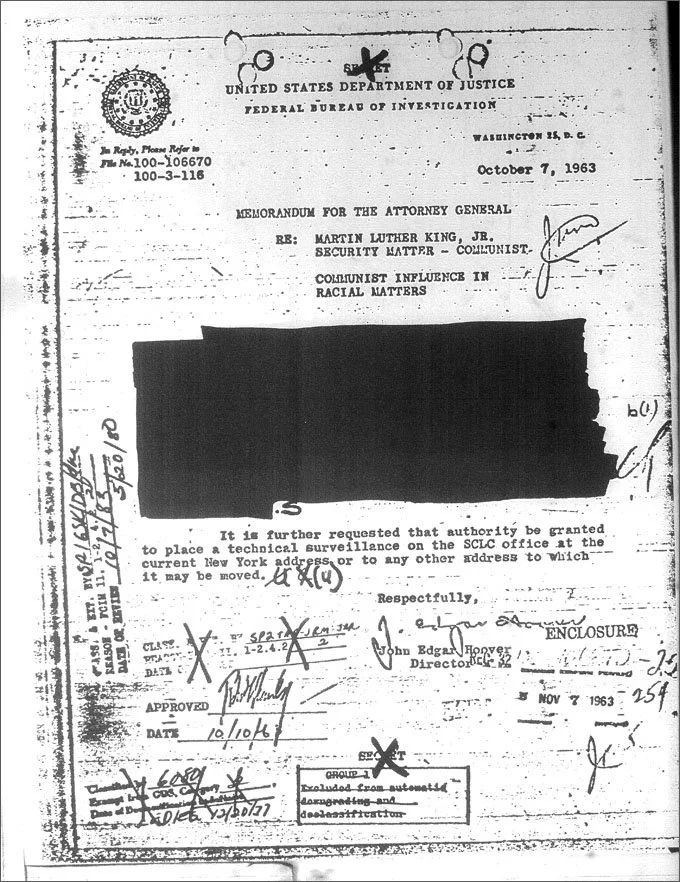

Answer: They collected information, spied on civil rights leaders (including Martin Luther King, Jr.), and spread misinformation.

The FBI, under J. Edgar Hoover, had a long history of investigating organized efforts by African Americans, including the 1940s March on Washington Movement.

As described the NPR interview with Tim Weiner (author of Enemies: A History of the FBI):

Hoover saw the civil rights movement from the 1950s onward and the anti-war movement from the 1960s onward, as presenting the greatest threats to the stability of the American government since the Civil War. These people were enemies of the state, and in particular, Martin Luther King [Jr.] was an enemy of the state. And Hoover aimed to watch over them. If they twitched in the wrong direction, the hammer would come down.

In the fall of 1963, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy approved wiretaps on all of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s telephones. The FBI even wrote threatening letters to King with the aim of coercing King to step down from his position as the head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

James W. Loewen notes in Lies My Teacher Told Me,

In August 1963 Hoover initiated a campaign to destroy Martin Luther King, Jr., and the civil rights movement. With the approval of Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, he tapped the telephones of King’s associates, bugged King’s hotel rooms, and made tape recordings of King’s conversations with and about women. The FBI then passed on the lurid details, including photographs, transcripts, and tapes, to Sen. Strom Thurmond and other white supremacists, reporters, labor leaders, foundation administrators, and, of course, the president…King wasn’t the only target: Hoover also passed on disinformation about the Mississippi Summer Project; other civil rights organizations such as CORE and SNCC; and other civil rights leaders, including Jesse Jackson.

After much public pressure and for political reasons, the FBI did investigate some cases such as the high profile murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner. But the portrayal of the FBI as central and heroic to the struggle for voting rights, as seen the film Mississippi Burning and elsewhere, is largely inaccurate.

Learn More

Tracked in America. This website explores the historical context and stories of individuals who have been targets of U.S. government surveillance during the 20th century. It includes timelines, interviews, and primary documents.

National Security Archive. Online access to declassified U.S. documents.

Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH) Sovereignty Commission Archive. All the documents from the Sovereignty Commission (an agency created by the state government to spy on and undermine the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi) are now online.

Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. By James W. Loewen. (Touchstone, 2007).

Q7: Which of the following had the most impact in the progress towards greater voting rights?

Answer: Grassroots activism and organizing.

SNCC staff leads volunteers in freedom songs during the second 1964 SNCC Orientation Session at Western College for Women in Oxford, Ohio. In the front of the audience, right, is Fannie Lou Hamer and, left, SNCC staff member Chuck Neblett. Courtesy McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi.

Inspiring leaders, large mass demonstrations, and eventually federal civil rights legislation and enforcement all contributed to changes toward greater equality, but grassroots organizers laid the essential foundation of the movement. Largely unacknowledged in textbooks, they performed the unglamorous, painstaking, and often dangerous work of building trust, commitment, and collective action toward local victories.

Charles Payne, the author of I’ve Got the Light of Freedom, explains:

The leaders were ordinary women and men–sharecroppers, domestics, high school students, beauticians, independent farmers–committed to organizing the civil rights struggle house by house, block by block, relationship by relationship.

The young organizers who were the engines of change in the state were not following any charismatic national leader. Far from being a complete break with the past, their work was based directly on the work of an older generation of activists, people like Ella Baker, Septima Clark, Amzie Moore, Medgar Evers, Aaron Henry. These leaders set the standards of courage against which young organizers judged themselves; they served as models of activism that balanced humanism with militance.

While historians have commonly portrayed the movement leadership as male, ministerial, and well-educated, Payne finds that organizers in Mississippi and elsewhere in the most dangerous parts of the South looked for leadership to working-class rural Blacks, and especially to women.

The federal government played a crucial role in enabling progress towards voting rights, but without the public pressure and information generated by grassroots organizing, the legislative and judicial victories won would not have come to pass.

Learn More

I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. By Charles Payne. 2007. University of California Press. One of the best books on the day-to-day grassroots organizing that was the primary, though less visible, work of the Civil Rights Movement.

Standing on My Sisters’ Shoulders. Film. By Joan Sadoff, Robert Sadoff, and Laura Lipson. 2002. 60 minutes. Documentary film on women in the Civil Rights Movement. While focused on Mississippi, it is useful for shining on a light on the people’s history of the Movement and in particular the role of women.

Civil Rights Movement Veterans website. Created by Veterans of the Southern Freedom Movement (1951-1968), this is where (as they explain), “we tell it like it was, the way we lived it, the way we saw it, the way we still see it. With a few minor exceptions, everything on this site was written, created, or spoken by Movement activists who were direct participants in the events they chronicle.

Critical Focus: The Black and White Photographs of Harvey Wilson Richards. This book of photographs is available for free for teachers. These photos depict the people’s history of the Civil Rights Movement and related struggles and demonstrate that racism and resistance were not limited to the southern states.

SNCC Digital Gateway: This digital gateway draws in documents, photographs, and audiovisual materials found at Duke and other SNCC-related collections in repositories across the country and uses them to chronicle the historic struggles for voting rights that youth, converging with older community leaders, fought for and won.

Q8: From the list below, the most commonly used strategy to organize for voting rights for African Americans in the south was:

Answer: Door-to-Door Canvassing

Ask anyone to describe the Civil Rights Movement and they’ll tell you about mass demonstrations, inspiring speeches, or sit-ins—challenging segregation. Organizing around voter registration required different tactics and skills.

As Emilye Crosby and Judy Richardson explain in The Voting Rights Act: Ten Things You Should Know, the work of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee exemplified the grassroots, door-to-door, organizing:

SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), an organization of young people that emerged from the 1960 sit-in movement, developed an approach to grassroots community organizing that has influenced every subsequent progressive movement. Their voter registration work in the Deep South was built around canvassing—going door-to-door, talking to people—and relied on patience, education, and building relationships. The work could be slow and tedious. It took place out of the spotlight, with few big or quick victories.

Influenced by Ella Baker and community leaders, the young people in SNCC made decisions by consensus, helped develop leadership skills in others, and challenged hierarchies that privileged wealth and education. In the summer of 1961, a group of about 16 young people put school and jobs on hold to become SNCC’s first field staff and commit to full-time movement work.

Over the next four years—working with other organizations and allies—SNCC was successful at organizing rural African American communities and making it impossible for the country to ignore the violence and discrimination at the heart of Jim Crow and white supremacy.

Though SNCC was not acting alone, their organizing was at the heart of the movement that moved people to insist that our country eliminate the legal basis of white supremacy. SNCC’s organizing led directly to the Voting Rights Act, expanding the electorate and ending the undemocratic stranglehold of the southern Dixiecrats. Their work made the national Democratic Party more explicitly representative (in race and gender).

Perhaps most importantly, SNCC recognized and nurtured leadership in people that the rest of the country had dismissed (like Hamer). Their alliance with these everyday people breathed new life into our democracy—challenging long-standing ideas of who and what was important.

Q9: Which of the following women were central to the struggle to win voting rights for African-Americans?

Answer: All of the Above

Mrs. Amelia Boynton was a stalwart with the Dallas County Voters League and played a critical role for decades in nurturing African American efforts to register to vote. She welcomed SNCC to town and helped support the younger activists and their work. When Judge Hare’s injunction slowed the grassroots organizing, she initiated the invitation to King and SCLC

Marie Foster was another significant local activist, teaching Citizenship classes even before SNCC arrived and remaining steadfast through the slow, brutal work of building a movement in the context of extreme repression. In early 1965 when SCLC began escalating the confrontation in Selma, Mrs. Boynton and Foster were both in the thick of things, inspiring others and putting their own bodies on the line. They were leaders on Bloody Sunday and the subsequent march to Montgomery. Whether working behind the scenes when the movement was just a handful of people or near the front of the line when the entire nation was watching Selma, they were courageous and unwavering.

Though Colia Liddell Lafayette worked side by side with her husband Bernard, recruiting student workers and doing the painstaking work of building a grassroots movement in Selma, she has become almost invisible and typically mentioned only in passing, as his wife. Her father and grandfather worked with the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and she was a strong organizer in her own right, founding an important NAACP Youth Branch in Jackson, Mississippi, and working for Medgar Evers before moving to Selma to organize with her new husband. She remained there until, at the request of SNCC Executive Secretary James Forman, she relocated to nearby Birmingham to help organize the spring 1963 demonstrations. In Birmingham, being pregnant offered no protection and she was badly injured when white officials used fire hoses to attack demonstrators.

Prathia Hall, a Philadelphia native who began working with SNCC in Southwest Georgia, joined the Selma effort in the fall of 1963 when the Lafayettes moved on to Nashville. Philosophically nonviolent, she was a brilliant organizer and orator who later became an ordained minister. She returned to Selma after Bloody Sunday to help SNCC and local activists figure out how to move forward.

Diane Nash, whose plan for a nonviolent war on Montgomery inspired the initial Selma march, was already a seasoned veteran, leading the Nashville sit-ins, helping found SNCC, and taking decisive action to carry the freedom rides forward. In 1961 she married Jim Bevel and then followed him out of SNCC and into SCLC. According to SCLC insider Andrew Young, “No small measure of what we saw as Jim’s brilliance was due to Diane’s rational thinking and influence.”

These are just a few of the many women who were critical to the movement’s success—in Selma and across the country. Like their male co-workers, they organized, demonstrated, taught, preached, and strategized. They also cooked and housed workers, tried to register, and recruited friends and neighbors. And, like men, they were threatened, attacked, beaten, and fired. Through it all they stood up for themselves and their communities, insisting on their “freedom rights.”

Source: “The Selma Voting Rights Struggle: 15 Key Points from Bottom-Up History and Why It Matters Today” by Emilye Crosby

Learn More

Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC. In Hands on the Freedom Plow, fifty-two women — southern and northern, old and young, rural and urban, black, white, and Latina — share their courageous personal stories of working for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) on the front lines of the Civil Rights Movement.

Womanpower Unlimited and the Black Freedom Struggle in Mississippi. Tiyi M. Morris provides the first comprehensive examination of the Jackson, Mississippi based women’s organization Womanpower Unlimited.

Standing on My Sisters’ Shoulders (Film). One of the best films on the Civil Rights Movement, this award-winning documentary reveals the movement in Mississippi in the 1950s and 60s from the point of view of the courageous women who lived it — and emerged as its grassroots leaders.

Q10: Which of the following groups has done the most to champion the concept of “one person, one vote,” regardless of race, class, or literacy?

Answer: Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

The concept of “one person, one vote,” regardless of formal education, literacy, class, or race was best championed by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee during the modern Civil Rights Movement.

John Lewis, speaking for SNCC at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, asserted, “‘One Man, One Vote’ is the African Cry, it must be ours too.”

As Emilye Crosby and Judy Richardson explain in, The Voting Rights Act: Ten Things You Should Know:

By 1963, in addition to helping people improve their literacy, SNCC began to challenge the whole idea of requiring literacy to vote. Bob Moses pointed out that white Mississippians used the political process to deny Blacks access to quality education and then used their poor education to deny them access to the political process. Moreover, they had encountered many people who had been denied an education but still had more than enough wisdom to vote on their representatives. Stokely Carmichael described the delegates selected to represent the Delta’s Congressional district at a state meeting of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party this way:

The “politically unsophisticated” people in their collective wisdom knew who could be trusted. Who deserved the honor. Who had earned the right. Who had a clear head and strong heart. The delegation was a cross section of service and merit, across sex and age, status or education. I mean you had the old warriors . . . who’d kept hope and dignity alive during some long, dismal, savage years. The valiant women . . . mothers of struggle. And too, the next generation, a few young college students, clearly intended to keep the struggle going. (Carmichael with Thelwell, Ready for Revolution, p. 394)

Learn More

SNCC Digital Gateway: This digital gateway draws in documents, photographs, and audiovisual materials found at Duke and other SNCC-related collections in repositories across the country and uses them to chronicle the historic struggles for voting rights that youth, converging with older community leaders, fought for and won.

Q11: The Black Panther symbol was first used by the:

Answer: The Black Panther symbol had its roots in the southern voting rights struggle in Lowndes County, Alabama.

When the Lowndes County Freedom Party was founded, Alabama law required that it have a symbol to help illiterate voters. They chose the Black Panther, indigenous to Lowndes, as their ballot symbol.

Learn why from this clip from the documentary film Eyes on the Prize.

Q12: In 2020, approximately how many people were legally denied the right to vote due to having been convicted of a felony?

Answer: An estimated 5.2 million Americans are denied the right to because of state laws that prohibit voting by people with felony convictions.

There is no federal law that protects the rights of a person who has been incarcerated to vote.

Felony disenfranchisement is an obstacle to participation in democratic life which is exacerbated by racial disparities in the criminal justice system, resulting in 1 of every 16 African Americans unable to vote.

From the Sentencing Project.

In the past 25 years, half the states have changed their laws and practices to expand voting access to people with felony convictions. Despite these important reforms, 5.2 million Americans remain disenfranchised, 2.3 percent of the voting age population. Learn more.

Meanwhile, people currently serving time in jail are counted by the Census as “residing” at their prison address. Those statistics are then used to draw legislative maps, which grants the people who live near large prisons extra influence at the expense of voters everywhere else and undermines the principle of “one person, one vote.”

It is estimated that there are more than 2.4 million people in 1,719 state prisons, 102 federal prisons, 2,259 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,283 local jails, and 79 Indian Country jails as well as in military prisons, immigration detention facilities, civil commitment centers, and prisons in the U.S. territories.

Because prisons are disproportionately built in rural areas but most incarcerated people call urban areas home, counting prisoners in the wrong place results in a systematic transfer of population and political clout from urban to rural areas. For example, 60% of Illinois’ prisoners are from Cook County (Chicago), yet 99% of them are counted outside the county.

Learn More

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. In this incisive critique, former litigator-turned-legal-scholar Michelle Alexander provocatively argues that we have not ended racial caste in America: we have simply redesigned it.

Q13: What measures are used today to discourage voting or politically disadvantage some populations?

Answer: All of the Above

Voter ID

Some states have put into place laws that require a person to show identification documents in order to vote. Studies have shown that Voter ID laws reduce voter turnout and that they disproportionately keep African-American and young people from voting. Voter ID proponents argue that requiring identification is necessary to cut down on rampant voter fraud. However, studies have shown that voter fraud is exceedingly rare.

Early Voting

Unlike many countries with higher voter turnout, in the United States elections are held on Tuesday, a day when most people are working. Allowing early voting is one way to ensure that all people have a chance to vote. The poor and people of color are among the largest beneficiaries of early, flexible voting.

In 2012, more than 157,000 Ohio voters cast their ballots during the days that have now been eliminated. Daniel Smith, a political scientist at the University of Florida, argued in an analysis conducted in support of suit against the state that Blacks have been disproportionately likely to use early balloting in the state and to vote early on the days that have now been canceled (data in other states suggest the same).

Gerrymandering

Gerrymandering is the process of redrawing political boundaries in order to give your political party greater numbers and thus a greater chance of winning power.

Gerrymandering has often been used to dilute the power of people of color by creating districts that fragment African-Americans and Latinos across a number of districts or concentrate all people of color in an area into one district to prevent African-Americans or Latinos from gaining a majority of votes on a municipal or county board.

For a current example of gerrymandering that has recently been in the courts, see the case of Florida’s Fifth District.

Denying the right to vote to the incarcerated or formerly incarcerated

As described in the answer to question 12, an estimated 5.85 million U.S. citizens are currently disenfranchised because they have a felony conviction.

Learn More

Q14: Approximately what percentage of eligible voters cast a ballot in the 2020 Presidential election?

Answer: 65%

Approximately 65% of eligible voters cast a ballot in the 2020 Presidential election, casting the most votes in U.S. history.

If you like this quiz, make a donation to Teaching for Change so that we can continue to develop and share resources on the Civil Rights Movement. Contact Teaching for Change with corrections and/or additions.

© Teaching for Change