What Happened to the Civil Rights Movement After 1965? Don’t Ask Your Textbook

Reading by Adam Sanchez

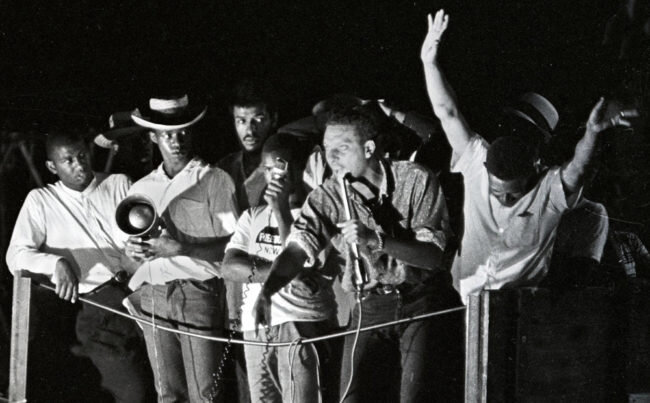

In 1966, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) chairperson Stokely Carmichael made the famous call for “Black Power.” Carmichael’s speech came in the midst of the “March Against Fear,” a walk from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, to encourage African Americans to use their newly won right to vote. But while almost every middle and high school student learns about the Civil Rights Movement, they rarely learn about this march — or the related struggles that continued long after the Voting Rights Act.

Most U.S. history textbooks teach a narrative that the Civil Rights Movement began with the Supreme Court Brown v. Board decision in 1954 and abruptly ended in 1965 with the passage of federal legislation. Not only does this narrative tell students that politicians and judges are more important than activists and organizers, it also reinforces the myth that structural racism is a relic of the past and the United States is on an unstoppable path of progress. As Black Lives Matter activists once again take up the fight against racial inequity and police brutality, excavating the long, grassroots history for students is crucial if we hope to use the past to inform our struggles today.

What Was the Civil Rights Movement?

With my high school students, I begin teaching the Civil Rights Movement by asking them to name the people and organizations that were involved.

“Martin Luther King!”

“Rosa Parks!”

Students shout out names like Emmett Till, Malcolm X, the Little Rock Nine.

I divide the whiteboard in half: Any person or group famous for events or actions before the Voting Rights Act of 1965, I write on the right side of the board; those famous for events or actions after the Voting Rights Act, I write on the left side of the board. Without fail, the right side of the board is always full and the left side of the board nearly bare.

After explaining to students what I had done, I direct their attention to a Civil Rights Timeline poster. We read aloud the first and last entries: “May 17, 1954, Supreme Court outlaws school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education” and “July 9, 1965, Congress Passes the Voting Rights Act.”

I ask: “Why don’t we ever learn about the Civil Rights Movement after 1965?” I don’t expect them to answer this right then, but I tell students that as we learn about the Civil Rights Movement — both before and after 1965 — I want them to consider this question.