The March on John Philip Sousa: A Social Action Project

Teaching Reflection by Elizabeth A. Davis

In 2022, John Philip Sousa Middle School was designated an affiliated area of Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park, thanks in part to the efforts of students at the school two decades ago who fought against its demolition and for its preservation as a historic landmark. Together with their teacher, Elizabeth A. Davis, they learned about the history of the school and the threat it faced.

The students developed skills in writing, speaking, drafting, and organizing — motivated by the goal of preserving the historic site. Davis reviewed and updated the article in 2020 while president of the Washington Teachers’ Union. She died in 2021, therefore we share this article in her memory and so that her activist approach to education and civic engagement can inform and inspire others.

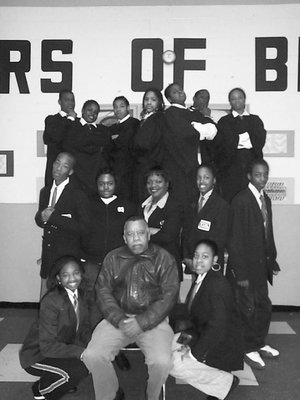

William Wilson with Elizabeth Davis and some of the sixth grade participants in the research project. © Pamela Parker

For at least a decade, John Philip Sousa Middle School where I taught in Washington, D.C. would only make the news when a neighborhood shooting would occur. I had no idea that the site of my vocation had a glorious history directly connected to the Civil Rights Movement.

A Washington Post article revealed that Sousa had been designated a landmark by the National Register of Historic Places in 2001 for its role in the desegregation of public schools in the District of Columbia.

After sharing the article with each of my four technology education classes, my 6th graders wanted to know, “What is desegregation and why did it make Sousa a historic landmark?” My 7th and 8th graders wanted to know:

Spottswood Thomas Bolling Jr. and his mother Mrs. Sarah Bolling. © The Washington Post by permission from the Washingtoniana Division

Does this mean that Sousa will become a museum?

When and why was Sousa segregated?

What does all this have to do with us right now?

My students and I learned that Sousa was one of the schools and cases (Bolling v. Sharpe) cited in the famous 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision. For many of my students, the Civil Rights Movement had seemed distant and disconnected from their lives. Together, we explored the history with internet searches, articles, and lively discussions. Although I perceived this as the perfect teachable moment, with connections to the lives of my students, I never imagined that this effort would take on a life of its own unexpected civil rights lessons before its completion.

Reading, Writing, and Researching Sousa’s History

Students began by researching Bolling v. Sharpe. Learning about Spottswood Bolling’s story led them to Brown v. Board of Education, then to Plessy v. Ferguson and the origination of the “separate but equal” law. After reading her child’s article about Bolling’s case, one parent donated the two-part video of the movie Separate But Equal. Students viewed and discussed the movie in 30-minute clips throughout the various phases of the project. The movie was an important venue for adding a third dimension to this valuable lesson on the Civil Rights Movement. It literally brought the story as close to life as possible.

As students became more curious about Spottswood Bolling, they began to ask parents, teachers, and community members about him. Their inquiry inspired them to read Through My Eyes: The Ruby Bridges Story to gain a deeper understanding of what it was like for Black students like Linda Brown, Spottswood Bolling, and Ruby Bridges to be the first to integrate an all-white school.

Examining racial discrimination through the eyes of a Black girl growing up in the South and a Black boy who grew up in their neighborhood helped to deepen their understanding of racism, discrimination, and inequity. It enabled them to identify current examples of each in their school, community, and institutions of the larger society. Although enhancing literacy was one of the underlying goals of the project, critical literacy became one of the more ambitious objectives. My desire was to not only read the lines of the text, but to also read between the lines. I wanted them to be able to answer questions about what they had read, while critically examining the text and questioning its validity. As a teacher committed to social justice, I believed that this would prove to be one of the most valuable lessons my students would gain from this project.

Since I continued to be only about a quarter of a step ahead of them in their inquiry, I became the “guide on the side” rather than the “sage on the stage.” I mastered the art of answering their questions with more questions. Although it was unsettling at first, I soon began to embrace the notion that this simultaneous, collaborative pedagogy could possibly become the practice for the duration of a unit of study. Each piece of research generated new questions and deeper inquiry. I happily joined the community of learners as a student and co-collaborator rather than “the teacher.”

Parents, Partners, and Other Collaborators

Students, teachers, parents, and community members collaborated to identify persons from the community who could give expression to what it was like to grow up during this era. Rita Dozier, the PTA president and parent of one of my students, was able to contact William Wilson, a community representative who attended school with Spottswood Bolling. Wilson, a public school advocate and an icon in the Marshall Heights community, was also the president of the Ward 7 Council on Education. He agreed to talk to my students about some of his experiences growing up as a Black youth in the era of “separate but equal.”

Students were awed that Wilson had been a classmate of Spottswood Bolling and that he was still living in the neighborhood. He described how he walked more than 30 blocks to and from Shaw Junior High School each day, even though Sousa was right across the street from where he lived. He offered a firsthand account of the story-behind-the-story of Spottswood Bolling. Students had so many questions that at their request, Wilson came back to serve as primary source throughout our study.

Shaw Junior High classroom, Washington, D.C., 1950. © The Charles Sumner Museum & Archives, D.C. Public Schools

Five years after Brown v. Board, are schools in the nation’s capital desegregated? © The Charles Sumner Museum and Archives, D.C. Public Schools

Making the Case to Save Sousa

On one of his visits, Wilson informed students that the D.C. Public Schools Board of Education had voted to allocate $14 million to demolish Sousa and build a new school on the site. He explained that as a result, Sousa would lose its status as a historic landmark. After much discussion about the pros and cons of razing versus renovation and the significance of preserving one’s history, the students decided that the history of the school was too important to them and to the community to be destroyed. They set about making a case for saving the school’s designation as a historic landmark to the school board, the city council, and to the community.

Researching, reading, writing, and resisting became the order of the day. In addition to raising consciousness, another benefit was increased student awareness of the power of the pen and the need to be able to express ideas using the written word.

In launching the campaign, several audiences were considered. Students thought that their classmates, parents, teachers, and community members simply didn’t know enough about the school’s history or the significance of Bolling v. Sharpe to care about saving Sousa’s status as a historic landmark. They devised a plan to teach about Spottswood Bolling and his contribution to putting Sousa in the pages of history.

They also seized the opportunity to present their own vision of a “renovated” Sousa in 3D. Students were prepared to venture out and go wherever the cause led them to make their case.

Some students wrote articles for a special classroom publication called UPRISINGS. Some students sent letters to key school board and council members, while others drafted a petition supporting the renovation of Sousa. Kirk Washington, an 8th grader, said in his letter to the board that Sousa should be saved “Because I am an African American and Sousa is an important part of my history.”

Several teams from each class volunteered to plan “Spotlight on Spottswood Bolling Day,” which the principal had designated at the students’ request. Teams of students were dispatched to each homeroom to conduct orientations about Bolling v. Sharpe and make the case for saving the school as a historic landmark. In class, the teams debriefed and critiqued their performance in delivery and knowledge of the subject. Some were overconfident about their delivery while others needed reassurance that they had done a great job. After reading the audience evaluations, they all felt a sense of accomplishment.

The willingness of students, teachers, support staff, and parents to sign the petition was an indication that the campaign was working. Students were starting to realize their own power. They now had the confidence and motivation to continue.

Students Redesign Sousa

Although the architectural planning committee and the board favored the least expensive option of razing Sousa to build a new one, they were obligated to seek community input before taking action. Neither the board nor the architectural planning committee anticipated the animated response from students, parents, and the community. Traditionally, parents in this low-income African American community have neither been valued as informed decision makers nor had they been engaged in policy decisions made in or about the school. In general, civic engagement is negatively impacted by the District of Columbia’s lack of congressional representation. The failure of local school leaders in predominantly low-income communities of color to cultivate participatory decision-making is also a factor. A history of discrimination based on race and class continues to thrive in Washington, D.C., a city noted for the role it played in the racial desegregation of public schools in our nation.

Students attended the architectural planning team’s community meetings and were the primary voices arguing for the school’s preservation.

The 98 students working on the campaign to save the school decided to create their own vision of a renovated school. They learned from Wilson that compromising the integrity of the structure in any way would result in the school losing its designation as a historic landmark.

As a prologue to the letter and petition writing and conducting the schoolwide orientations, they designed and constructed a scale model of their vision for the renovated Sousa. Each student chose an area of the school to redesign. Classrooms and labs, circulation spaces, cafeteria, main office, gymnasium, museum/lobby, auditorium, and playground were just a few of the areas selected.

Christina Hayunga, a volunteer architect, came to the school once a week for two months to advise the students about elements of design such as space, scale, and functionality: three essentials considered when planning any structure. After the models were completed and consolidated to make up the total school design, they were exhibited at the Capital Children’s Museum for two months. An open house was held at the museum for students, parents, community members, and school staff at the end of the school year. At the National Writing Project’s Spring 2002 Conference, four of the students presented a part of the model, student articles from UPRISINGS, and reviews of the Supreme Court cases related to Sousa’s history.

Campaign Victory

© Capitol Community News, Inc.

As they continued their investigation of the Spottswood Bolling story, students were ecstatic to learn that the board of education decided to allocate an additional $4 million for Sousa’s renovations. They were equally excited about the critical role they played in continuing the legacy of Spottswood Bolling. Students realized that they had gained a restored, state-of-the-art, 21st-century school while preserving Sousa’s status as a National Historic Landmark.

They learned the power of collective actions to achieve a goal. They began to understand that the Civil Rights Movement was not merely one event orchestrated by one or a few people, but a series of events and actions, collaboratively and strategically planned and carried out by many to achieve equity and justice for all. Students began to understand how they continue to benefit from events that occurred over a century ago to secure civil and human rights for people of color. The research project helped them to see that the Civil Rights Movement is not really an era that has ended, but an ongoing struggle requiring their engagement as responsible citizens who seek to secure and maintain a just society for everyone.

Most important, I believe that they learned the value and responsibility of rising up and resisting injustice. One thing I am certain that my students and I both learned is that there is no victory without struggle. History, particularly the historical events related to the Civil Rights Movement, has taught us that. ■