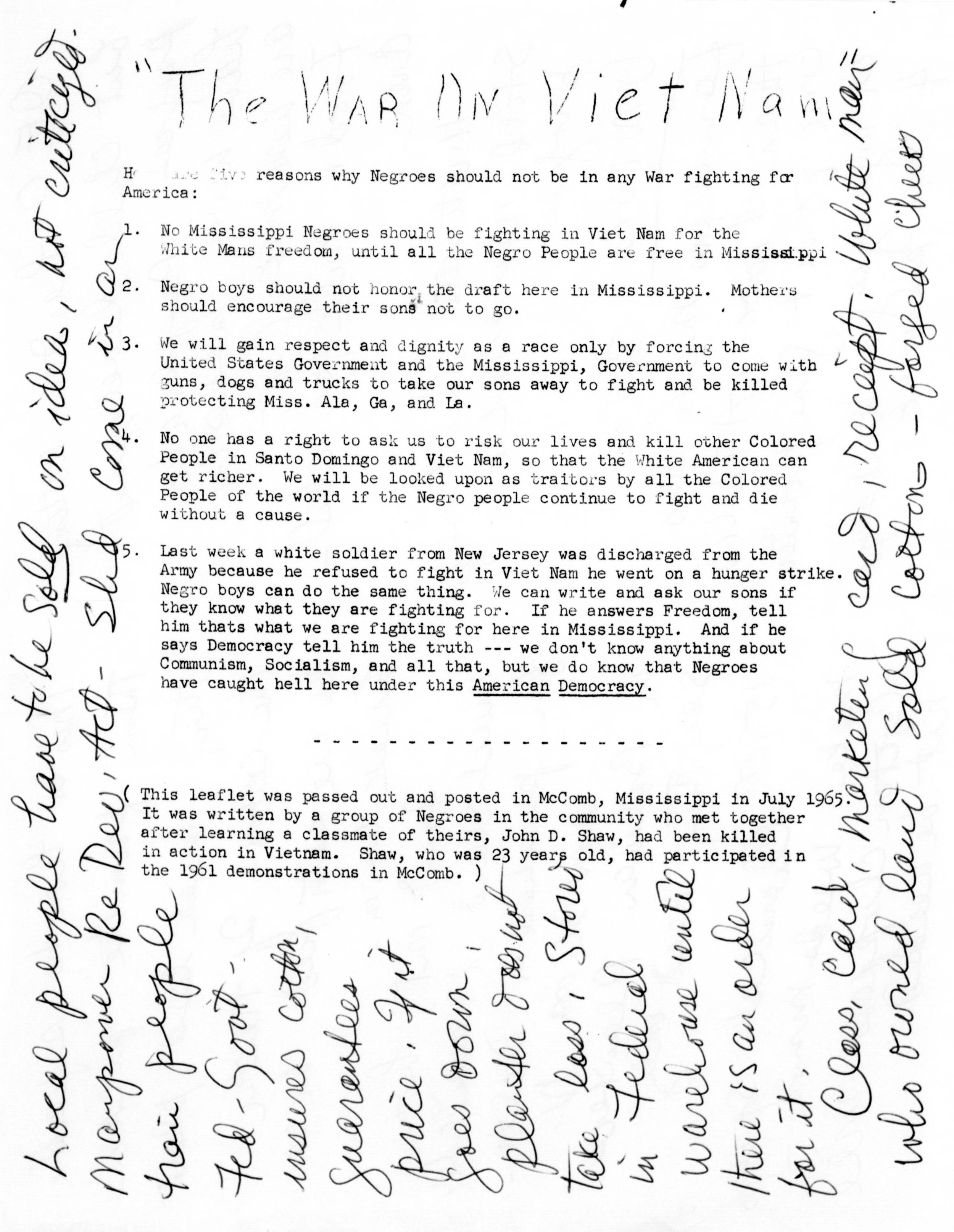

McComb Statement Against the Vietnam War, July 1965

Reading by SNCC Digital Gateway

In late July 1965, a group of young activists in McComb, Mississippi’s Movement learned that John Shaw, one of their former classmates at Burglund High School, was killed in combat in Vietnam. The news stung them and that he was fighting in Vietnam seemed hypocritical — Why should young Black men fight and die in far-off Vietnam when first-class citizenship and freedom was denied to them in Mississippi? They wrote and released a broadside declaring in part that “Negro boys should not honor the draft [and] mothers should encourage their sons not to go.” Their public denouncement was the first anti-war statement from within the Civil Rights Movement and paved the way for SNCC to take a stance against the war.

McComb’s Anti-Vietnam War Statement, July 1965. The handwriting around the edge appears to be about labor organizing that was going on at the time, possibly for "Strike City." The flier was being used as notepaper. See the reference at the end to "Plants agree to keep labor unions out." Wisconsin Historical Society; Lucile Montgomery Papers, 1963-1967.

Connecting white supremacist violence at home with the escalating violence in Southeast Asia was not difficult. By the time Shaw died in combat, many Black people in McComb felt that the war in Vietnam was “for the White Man’s freedom,” not theirs. SNCC had first come to McComb in the summer of 1961, brought there by local NAACP leader C. C. Bryant. It was the organization’s first voter registration project in the Deep South and was met with extreme violence from the white community. McComb and its surrounding counties were notorious Klan strongholds. In September, two months after SNCC’s arrival, Herbert Lee, a strong NAACP supporter of the effort, was gunned down in broad daylight at a cotton gin in neighboring Amite County. His killer was acquitted that same afternoon, claiming self-defense.

SNCC left the region not long after and did not return until three years later. During this period — the 1964 Freedom Summer — a county chapter of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) was formed. SNCC, now working under the umbrella of COFO, also helped organize a local Freedom School, which under the direction of Ralph Featherstone pushed students to explore their history and heritage while also encouraging them to participate in the Movement.

The revitalized civil rights activity was once again met with white terrorism. The church that hosted the Freedom School was bombed. So was the home of C. C. Bryant, who fought back against the nightriders with his new high-powered rifle. And after most of the volunteers left at the end of the summer, terrorism continued. In September, the Klan bombed the home of one of SNCC’s earliest supporters, Aylene Quin, with her two young children inside.