The Unknown Origins of the March on Washington: Civil Rights Politics and the Black Working Class

Reading by William P. Jones

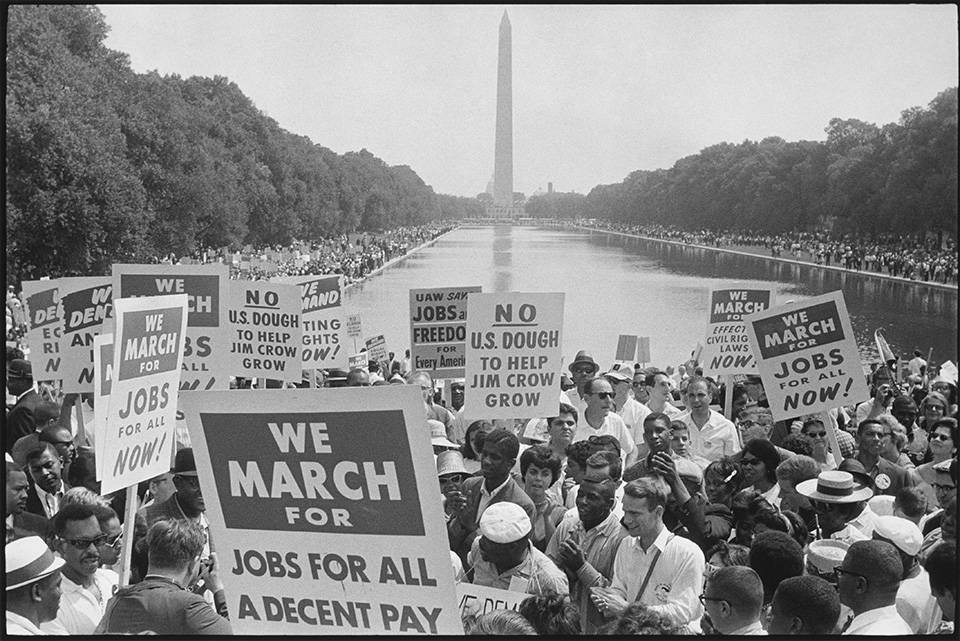

Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos

“The very decade which has witnessed the decline of legal Jim Crow has also seen the rise of de facto segregation in our most fundamental socioeconomic institutions,” veteran civil rights activist Bayard Rustin wrote in 1965, pointing out that black workers were more likely to be unemployed, earn low wages, work in “jobs vulnerable to automation,” and live in impoverished ghettos than when the U.S. Supreme Court banned legal segregation in 1954.

Historians have attributed that divergence to a narrowing of African American political objectives during the 1950s and early 1960s, away from demands for employment and economic reform that had dominated the agendas of civil rights organizations in the 1940s and later regained urgency in the late 1960s. Jacquelyn Dowd Hall and other scholars emphasize the negative effects of the Cold War, arguing that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and other civil rights organizations responded to domestic anticommunism by distancing themselves from organized labor and the Left and by focusing on racial rather than economic forms of inequality. Manfred Berg and Adam Fairclough offer the more positive assessment that focusing on racial equality allowed civil rights activists to appropriate the democratic rhetoric of anticommunism and solidify alliances with white liberals during the Cold War, although they agree that “anticommunist hysteria retarded the struggle for racial justice and narrowed the political options of the civil rights movement.”

Meanwhile, Thomas Sugrue, Nancy MacLean, and Timothy Minchin focus on renewed attention to economic inequality in the late 1960s, attributing it to a resurgence of black working-class activism inspired by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and a resurfacing of radical voices previously “driven underground by McCarthyism.” These and other studies remind us that Rustin, A. Philip Randolph, and Martin Luther King Jr. remained committed to economic radicalism between 1954 and 1965 but portray them as isolated individuals who, as Sugrue writes of Randolph, “did not have much of a movement under his aegis.”